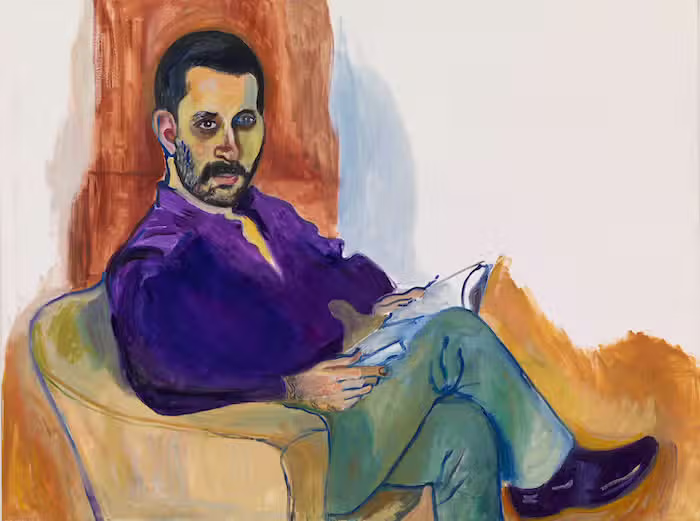

Alice Neel, Jackie Curtis as a Boy, 1972. Image courtesy of The Estate of Alice Neel and David Zwirner.

How does one discuss an artist whose work is both specific and panoramic? Should the conversation zoom out to capture the breadth of her subjects: family, loved ones, neighbors, artists, literary figures, activists? Or hone in on particulars such as when or at whom she was looking? When it comes to Alice Neel, David Zwirner has landed on the latter in an ongoing series of exhibitions that offer intimate windows into the late artist’s five-decade-long practice. Guided by curator and writer Hilton Als, the latest exhibition culls from Neel’s vast catalog to reveal a deeply human portrayal of queerness.

“At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World” opens today at the gallery’s Los Angeles location and will be accompanied by a catalogue featuring writings by Als, Alex Fialho, Evan Garza, and Wayne Koestenbaum. The exhibition features rarely seen portraits of poets Frank O'Hara, Allen Ginsberg, and Adrienne Rich, among others. The curation both uplifts those from its direct lineage but also expands, porous and pliable, to encompass those who as Als puts it in the exhibition text “would qualify as queer by virtue of their different take in their given field and thus the world.” That these works are all displayed together is the result of an ongoing dialogue between Als and the late painter.

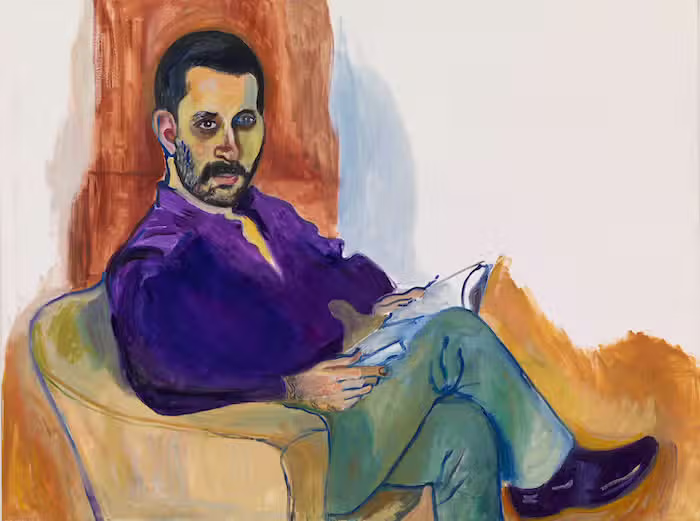

Alice Neel, Brian Buczak, 1983. Image courtesy of The Estate of Alice Neel and David Zwirner.

Als grew up in Brooklyn in the ‘70s when Neel, decades into her practice, was finally getting her flowers. When he first saw Neel’s work in a book as a young man, he was taken aback by its once “outrageous and accurate” portrayal of people: the jarring colors, the exaggerated shapes, the wobbly lines, as he described in a 2017 essay. As his eyes lingered, he began to see himself in these portraits. “What did it matter that I grew up in a world that was different than that which Linda Nochlin, Andy Warhol, and Jackie Curtis, inhabited?” he wrote. “We were all as strong and fragile and present as life allowed. And Neel saw.” This initial thrill and sense of discovery follows Als into his curatorial work. For every layer he peels back, mystery still seems to seep in. “She was not, in short, limiting her view to people who looked like herself,” he added of her generous approach.

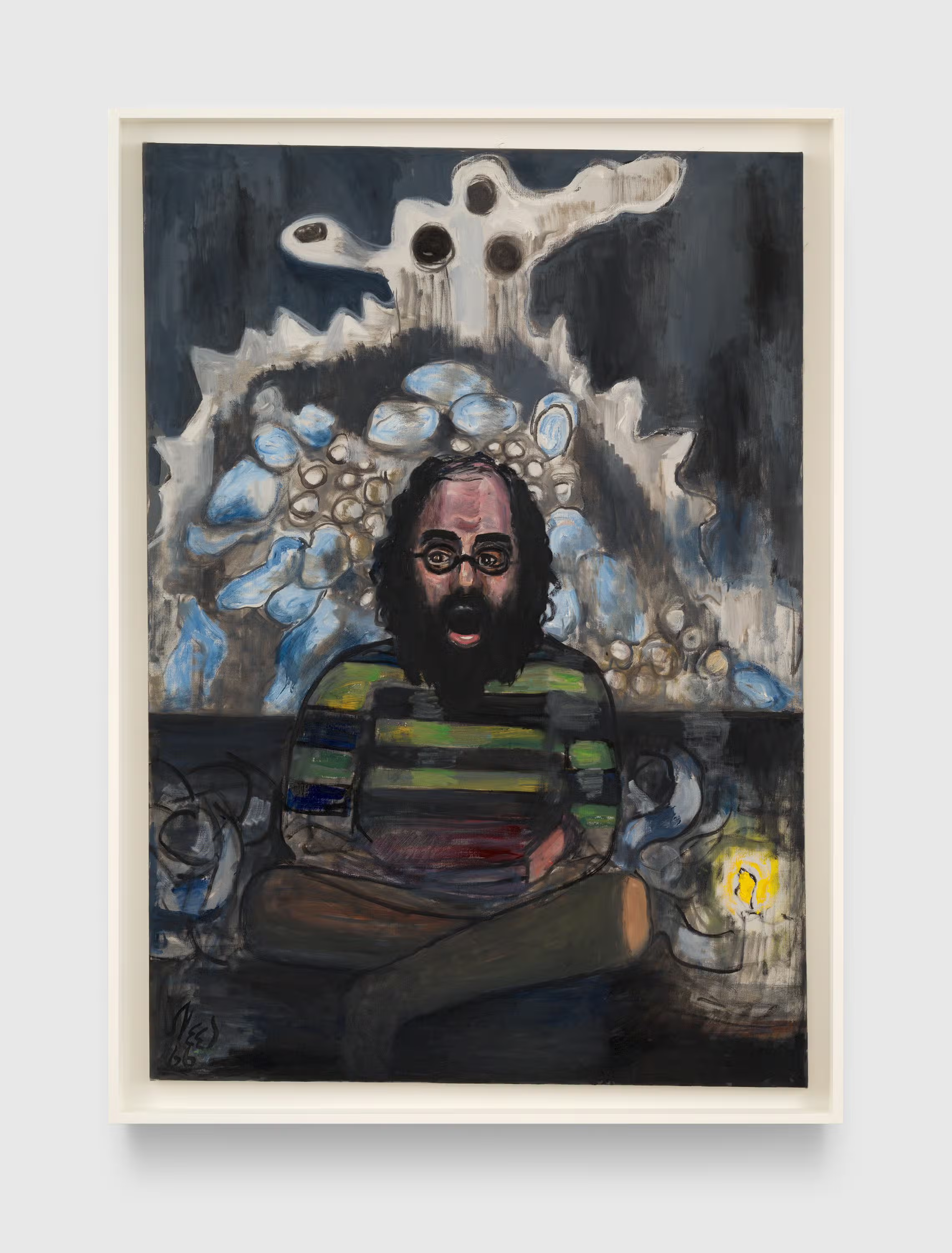

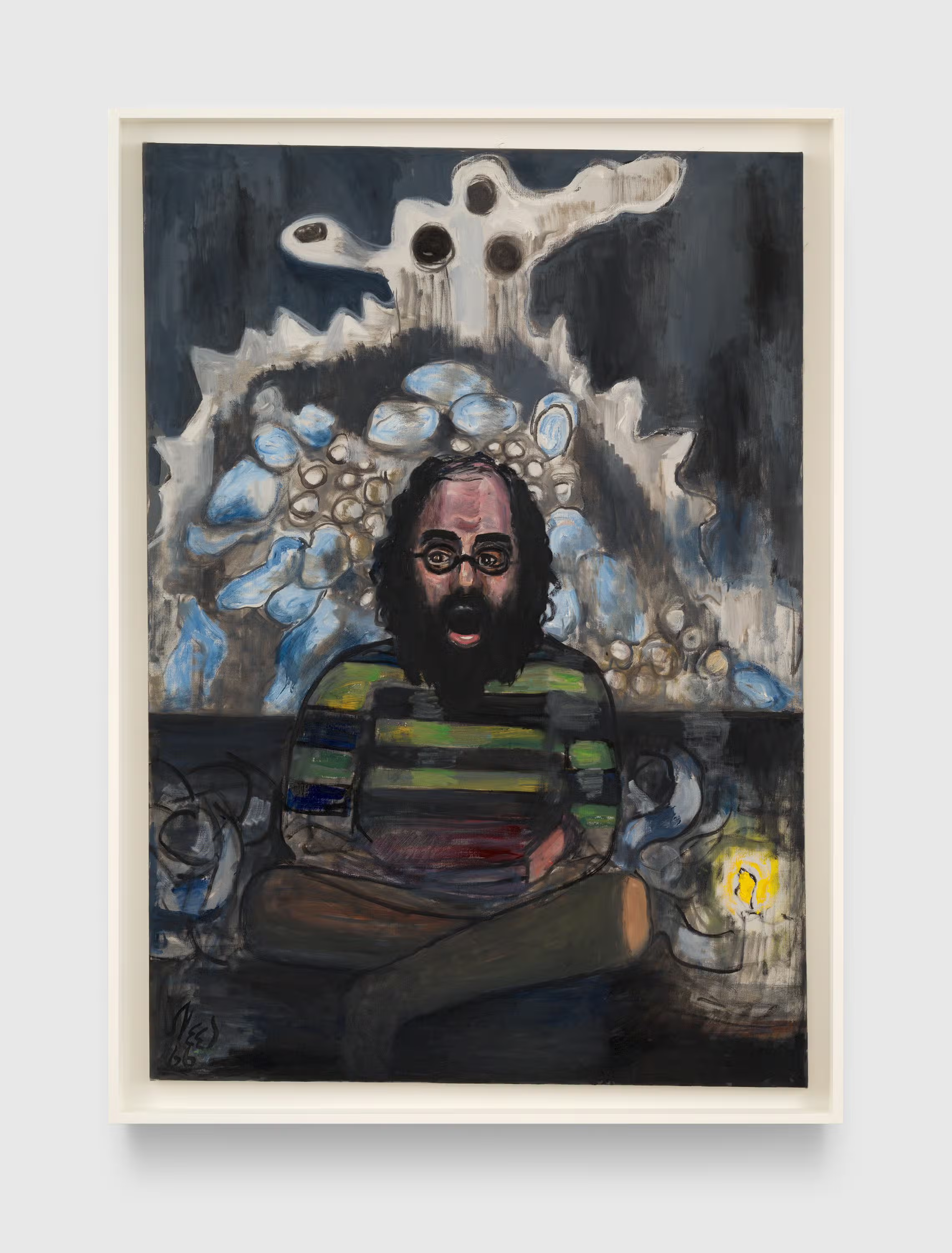

Neel’s painting Allen Ginsberg, on view in the show, depicts the openly gay poet sitting with his legs crossed on the floor. His mouth is open in an "O" shape, and his eyes glance off to the side, illuminated by a candle that casts a kaleidoscopic, blue-tinged display of ambiguous pebble-like shapes above his head like a halo, perhaps swirling with ideas. The portrait was painted by Neel in 1966. Ginsberg's mother, a communist like Neel, whom he had a compliccated realtionship with, had passed away a year earlier. Nationally, it was a time of upheaval, of activism and resilience in the face of systemic oppression. It was the year that the Black Panther Party was founded. The same year of San Francisco's historic Compton's Cafeteria Riot, where trans women and their allies stood up against police harassment—a precursor to the pivotal Stonewall riot in New York three years later. A year of heightened anti-war sentiment bubbling up in response to America’s presence in Vietnam.

Alice Neel, Allen Ginsberg, 1966. Image courtesy of The Estate of Alice Neel and David Zwirner.

A bard of the times, Ginsberg was “not afraid/ to speak my lonesomeness in a car,/ because not only my lonesomeness/ it's Ours, all over America,” as he wrote in his anti-war poem Wichita Vortex Sutra that same year. The poet's introspective study of the human condition resonates in Neel's ability to animate the emotional landscapes of her subjects—it also speaks to Als’ own writing and curating, in which he seeks out both the palpable commonalities and the boundless uniqueness of each soul.

"There is a difference between visions and visionaries," says Als as he gestures to the painting on opening night. "When you have a vision, one could say it's a hallucination or something you made up. But when you’re a visionary, you see the world before the world sees itself. This painting is about Alice’s visions, but it's also about an identification with a visionary."

Als’ first foray into Neel's practice was in 2017 when Zwirner asked him to curate what became the first overview dedicated to the painter's portraits of people of color. “Alice Neel, Uptown” consisted of paintings made over the five decades that the late Pennsylvania-born artist spent in Spanish Harlem and the Upper West Side. Among the images selected were ones of Black luminaries such as Horace R. Cayton Jr. and Harold Cruse, the Puerto Rican activist Mercedes Arroyo, as well as artists, students, families—neighbors who were part of her everyday life. Following his first successful foray into Neel’s practice, Als now turns his gaze to another community close to his heart.

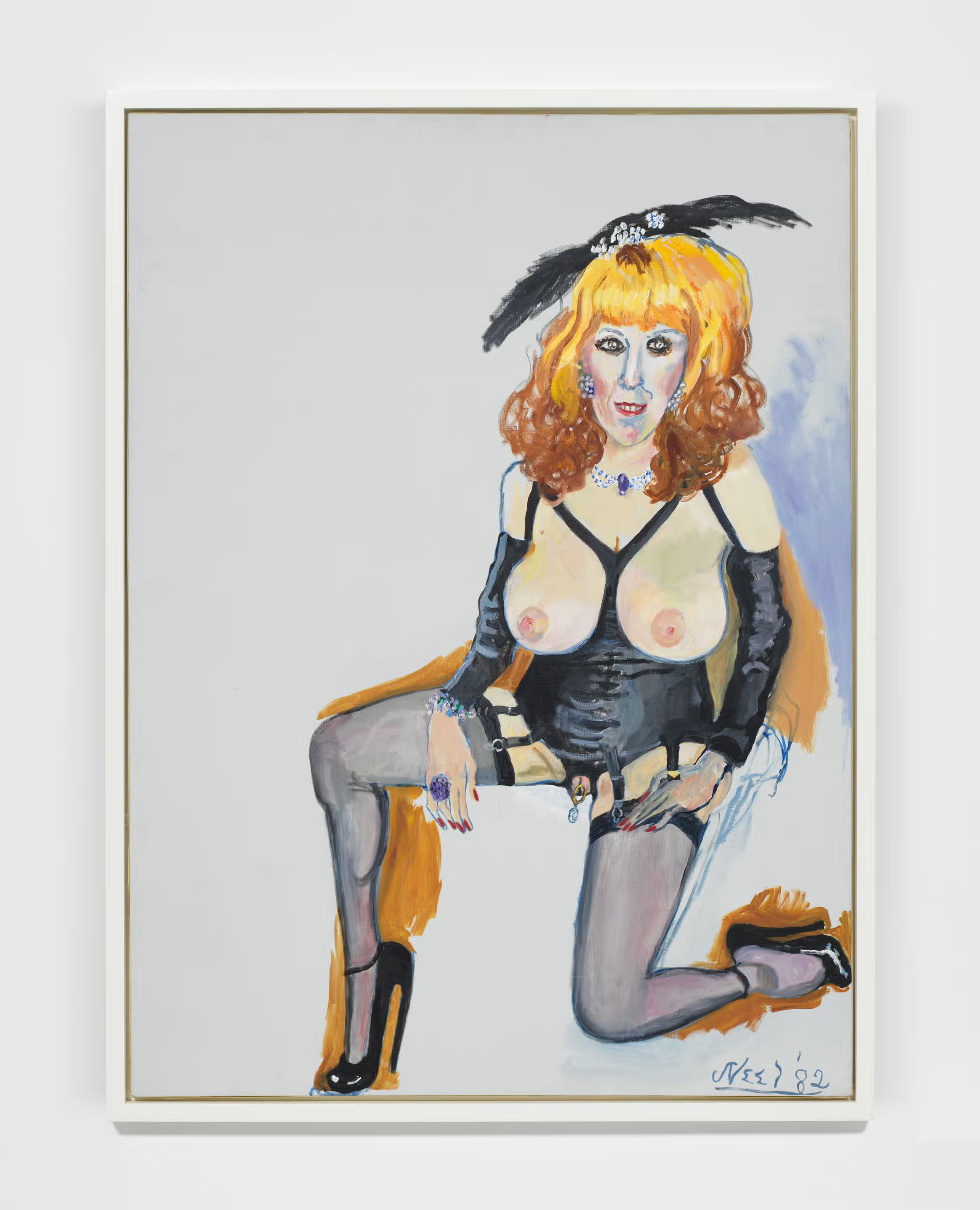

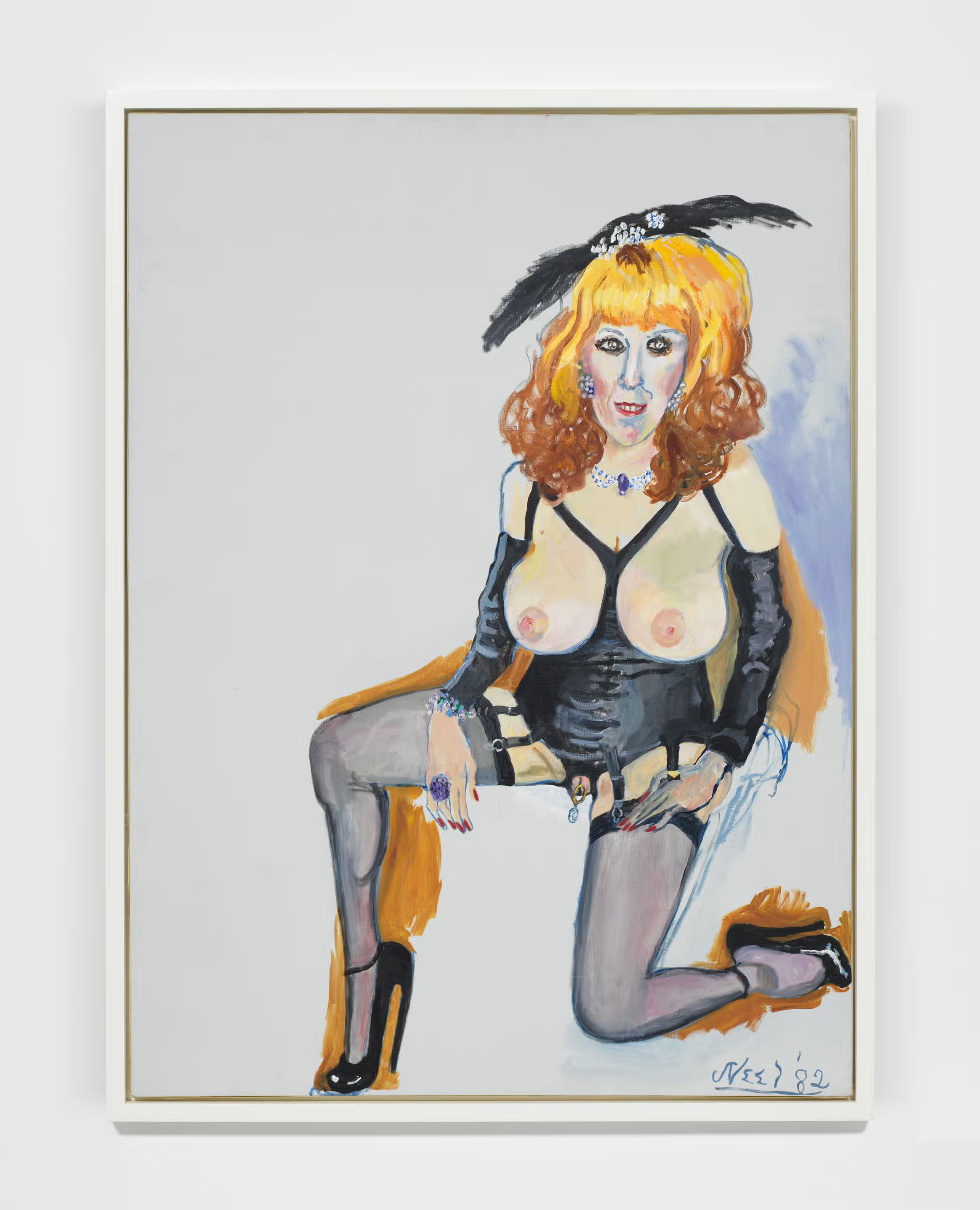

Alice Neel, Annie Sprinkle, 1982. Image courtesy of The Estate of Alice Neel and David Zwirner.

In one portrait on view at “At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World,” Jackie Curtis as a Boy, 1972, the performer and drag queen's gender fluidity and commanding presence is rendered in Neel's signature impressionistic brushstrokes. In Annie Sprinkle, 1982, the sexologist and performance artist poses in crotchless lingerie against a sparse backdrop. Poised and kneeling on one knee, breasts exposed, she wears costume jewelry (including a clit ring), a black decorative hat atop blond bangs, and stilettos. The image is intriguing and brazen: Who is this woman? I can’t help but wonder, catching a taste of the fascination Neel herself might have felt upon discovering such a dynamic subject.

Neel’s expansive eye was well suited for such marginalized identities too often placed into diminutive, reductive boxes. As she sought out to capture the world as she saw it, her open-minded way of looking saturated her paintings and unfettered her subjects from stereotypes too small to contain the breadth of their being. Here, the LGBTQ+ community is documented not for its otherness but for the artist’s pursuit of the individuality that unites all of humanity.

"Queerness is not the exception, it's the rule," says Als, underscoring the lack of queer visibility during the years Neel was painting. "One of the reasons that we wanted to do a show was to show the ways in which the normalization of a person’s life, whether they were Black or white, gay or straight, was part of the narrative that Alice was telling. Once you welcome people into your home, once you welcome them into your gaze, there is a way in which this is normalized," he continues. "I love how unexceptional people become in her work, only because the unexceptional means that you are left with yourself: You’re left with this “I."

At Zwirner, a composite image of many "I"s emerges, a window into the late visionary artist's unflinching and inquisitive way of looking at the world. “We still have difficulty with women artists who look. Women are taught to often when they see something in distress or different to help or to look away. Alice is one of those people who felt if you look away you are denying the personhood," says Als. "The political is personal."

“At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World” is on view until November 2, 2024 at David Zwirner Los Angeles at 606 N Western Avenue, Los Angeles 90004.

.avif)