Installation view of “Monstrous Beauty: A Feminist Revision of Chinoiserie. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Patty Chang forcefully eats a cantaloupe installed in her bra while balancing a generic white porcelain plate on her head. As the performance artist addresses the camera in a fictional monologue for her film Melons (at a Loss), 1998, she explains how she inherited a cheaply made saucer from her aunt who passed away from breast cancer. On the other end of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition hall, Chang’s full-size massage table Abyssal, 2025, made from unglazed porcelain and punctured with orifices, in reference to the murder of six Asian spa workers in Atlanta in 2021 and the empty promises of equality, Chang’s poignant works are part of “Monstrous Beauty: A Feminist Revision of Chinoiserie,” an incisive group exhibition at the Met that pairs historical ceramics with works by seven contemporary Asian women artists.

“The museum is somewhere we tend to think of as a space sealed off from the world,” says associate curator Iris Moon, who works in the museum’s collection of European sculptures and decorative arts. “Being away from the space during the pandemic granted the time to think about how to bring the world outside into the museum's collection.” The result is an exhibition that reckons with the origins and lasting impact of Chinoiserie—a European aesthetic movement inspired by imagined visions of China, and by extension other parts of Asia, during the so-called Age of Discovery.

Lee Bul, Monster Black, 2011 reconstruction of 1998 work. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

From 16th-century porcelain recovered from shipwrecks to 19th-century mass-produced kitsch, the Met presents a well-researched and expansive timeline of how these objects influenced Europe’s reductive attitude towards Chinese identity, particularly in relation to women. The exhibition recontextualizes uninformed European fantasies of the “Orient” that obscured the realities of Asian craftsmanship and culture. These works acted as vessels for displaced Western anxieties around female excess, unsanctioned sexuality, and interracial mixing—tropes that eventually birthed a contemporary culture that normalizes fetishization of and violence against Asian women. The works on view by contemporary Asian women artists direct this misrepresentation toward generative ends as they interrogate, deconstruct, and reassemble material artifacts and cultural imaginaries.

A glazed ceramic work by Heidi Lau, who was raised in Macau, China and lives in New York, leans against the gallery wall. From the Heart of the Mountain Anchored the Path of Unknowing, 2023, has an elongated, algae green form that simultaneously evokes an ailing tower, a tree engulfed in overgrowth and wounds, and a ladder. The New York-based artist Jen Liu’s The Land at the Bottom of the Sea, 2023, recuperates the underwater world as a site of mystery, where two Taiwanese actresses in the role of mermaids engage in sentimental exchange and choreographies of coupling and decoupling. The video’s second part animates a satirical critique of how Western standardization strips the sea of its otherworldly beauty.

Porcelain and pepper from the VOC trading ship the Witte Leeuw, anonymous, before 1613. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Displayed alongside Lau and Liu’s works are Chinese ceramics rescued from shipwrecks and their European imitations. These artifacts trace European fascination with Chinese porcelain—and by extension, its aesthetic and literati culture—back to the Ming dynasty, when wares arrived through maritime routes. However, countless shipwrecks prevented delivery and inspired copies that spread across factories in Mexico, Indonesia, Japan, and Europe. These imitations were often riddled with mistakes as seen in the overtly ornamental or uncanny products on view.

Many of these products featured decorative color palettes and mythological creatures largely unbeknownst to China. The Medici family, Dutch trade centers, and Parisian courts collected and commissioned such works, framing Asia as a site of excessive luxury and feminine mystery. And as tea disseminated from ruling families, such motifs became a recurring presence in urban middle class households during the eighteenth century.

Two sweetmeat dishes, ca. 1750-60. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Chinoiserie also fueled nationalist and patriarchal myths that women are more emotional, as fragile and delicate as porcelain. William Hogarth’s early 1700s etching A Harlot’s Progress, Plate 2 depicts a woman throwing a tantrum by breaking a teapot and cups. The 19th-century European invasion of China further mutated these stereotypes into a full-blown sexual culture that violently degraded Asian women into objects of consumption.

The kind of porcelain objects we see in these homes often portray Chinese women’s sexual availability, uninhibited by European moral codes. In the oversexualized and grossly inaccurate soft-paste porcelain figurine The Laotian Goddess Ki Mao Sao and Worshippers, ca. 1750-52, a pseudo-Chinese goddess is seated above two kneeling worshippers with offerings; the back view reveals that one of the worshippers is grabbing her bottom. Elsewhere, the body of a Chinese figurine appears to be indistinguishable from the body of the vase, or alternatively entrapped in it in the racially ambiguous, objectifying Lidded vase with the head of a Chinese woman, 1765.

Yeesookyung, “Translated Vase," 2017-2024. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

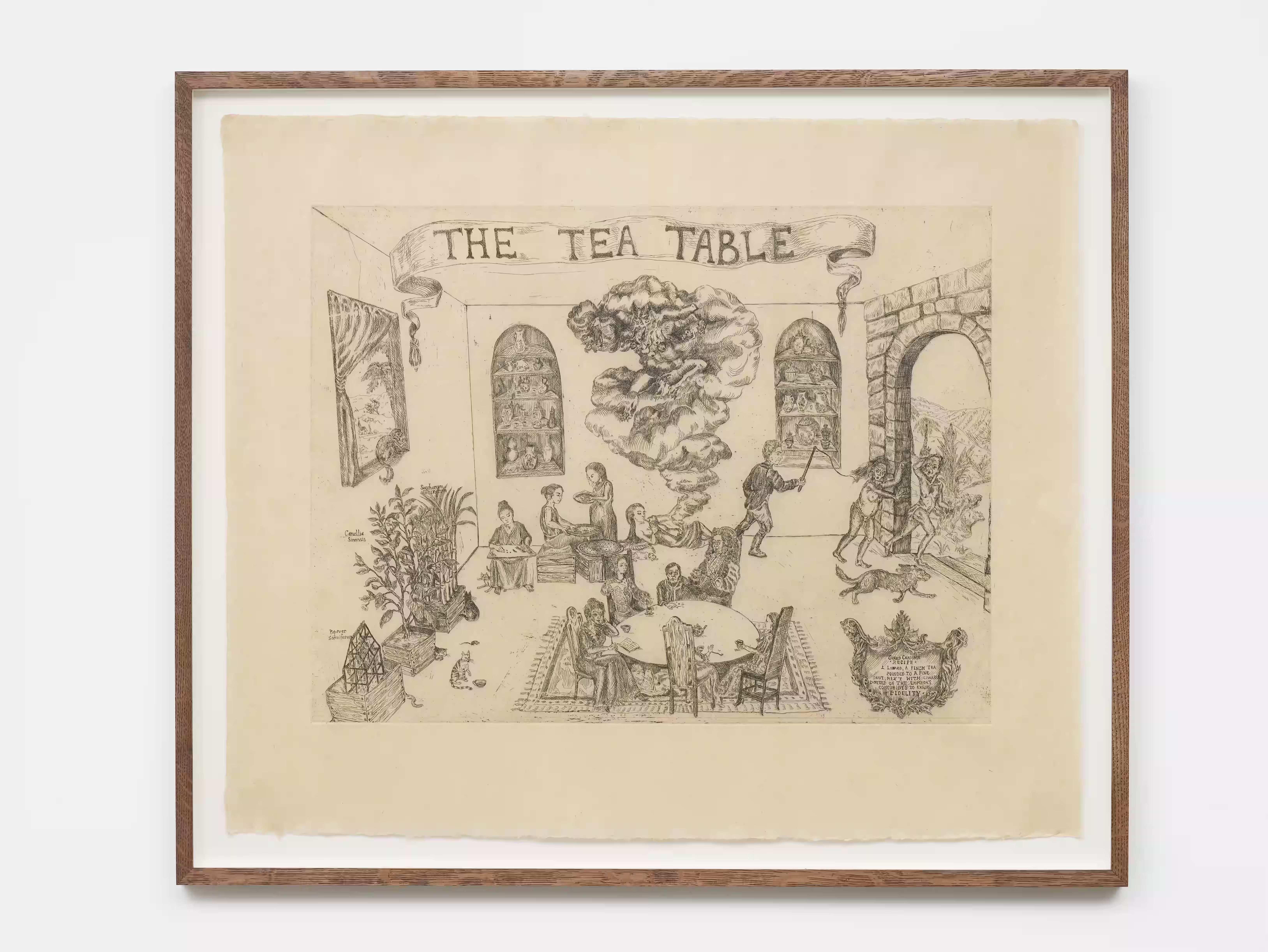

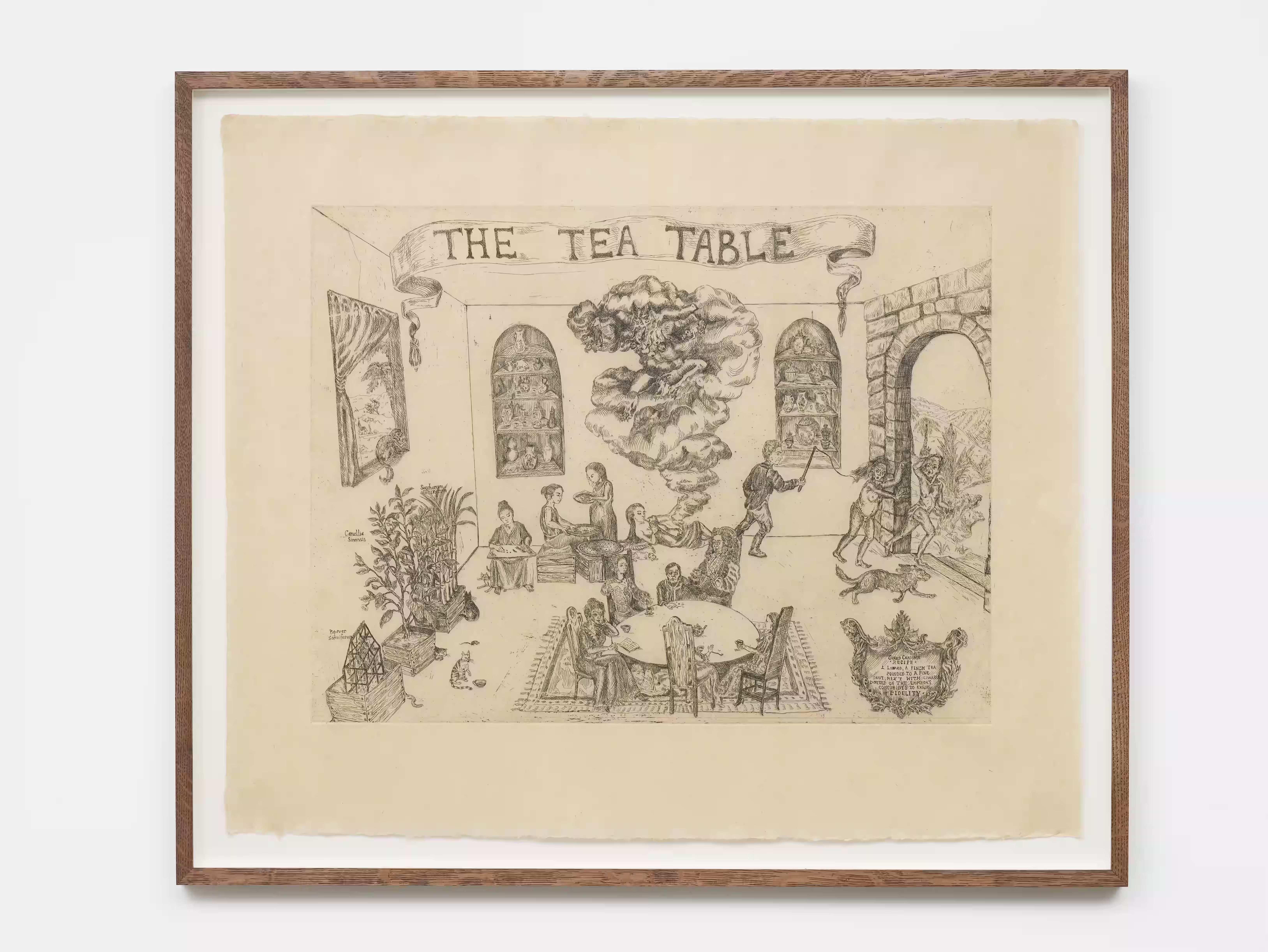

In contrast, Los Angeles-based artist Candice Lin’s drawing The Tea Table, 2016, juxtaposes a European tea party with scenes of colonial extraction: A demon grows out of an Indigenous woman’s opium smoke. The work draws on Lin’s own Chinese heritage and calls attention to the invisible gendered and sexualized violence that supported material wealth in Europe. South Korea-based Lee Bul’s fragmented, porcelain body parts Untitled (cyborg pelvis) and Untitled (cyborg leg), both 2000, interrogate the violent trope of the Asian cyborg woman. In Yeesookyung’s “Translated Vase” series, made between 2017 to 2024, the South Korean artist reconfigures ceramic shards into a fractured new whole that is organic, grotesque, alluring, and larger-than-life, alluding to our enduring attraction to violence.

“Looking at Chinoiserie through the lens of curiosity and critique brings into focus stories that have not been told before,” Moon reflects, adding, “you can still appreciate its beauty. If anything, seeing its historical complexities makes it an even more compelling subject.”

Candice Lin, The Tea Table, 2016. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The sensitive and encyclopedic curation of “Monstrous Beauty” traces the history of Chinoiserie and its entanglement with the history of colonialism and imperialism, suggesting that its harm has yet to be undone. It is up to the younger Asian generations entering a world not built for us channel creative forces and champion artists that can render history anew.

“Monstrous Beauty: A Feminist Revision of Chinoiserie” is on view through August 17, 2025 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art at 1000 5th Ave, New York, NY 10028.

.avif)