.avif)

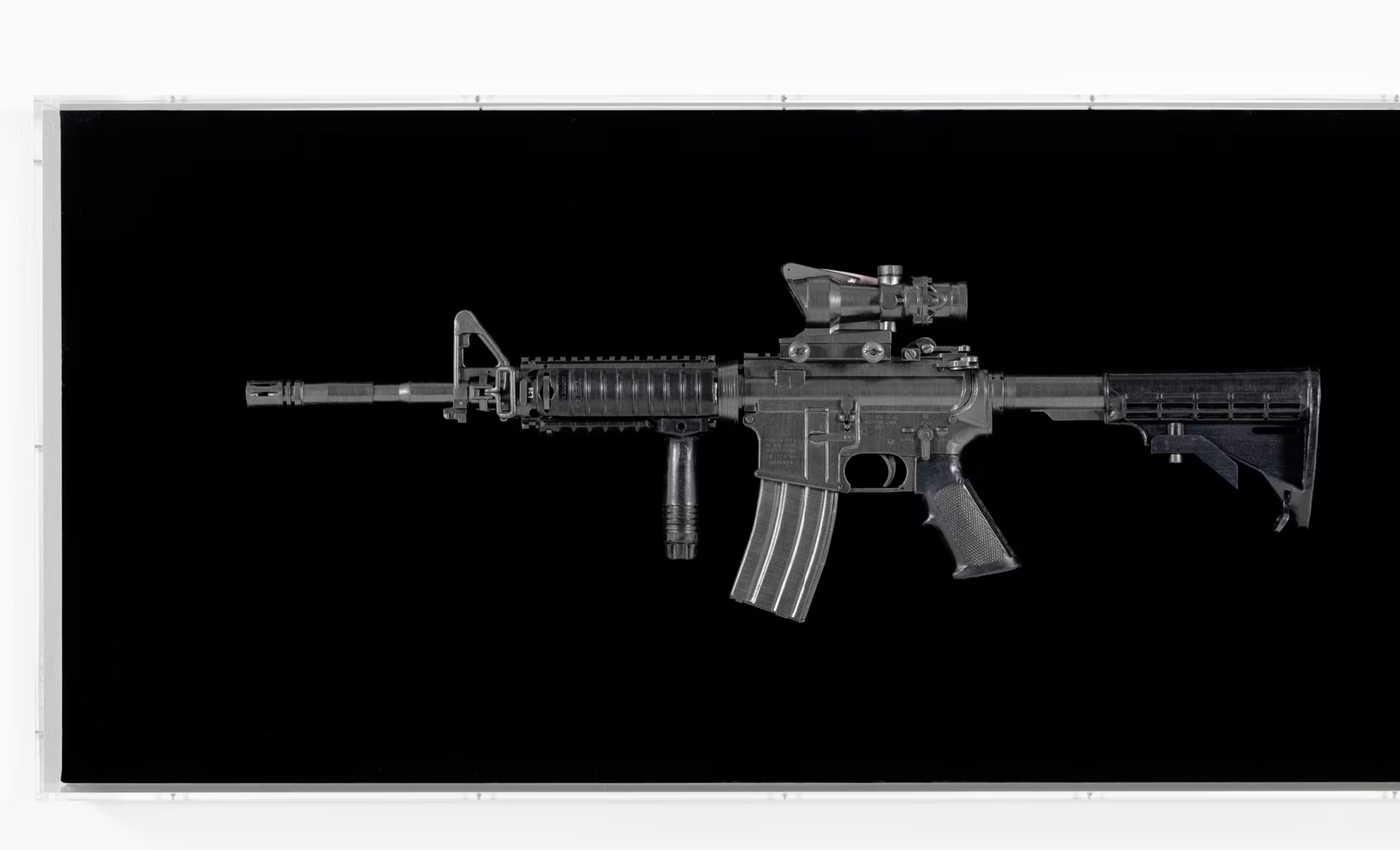

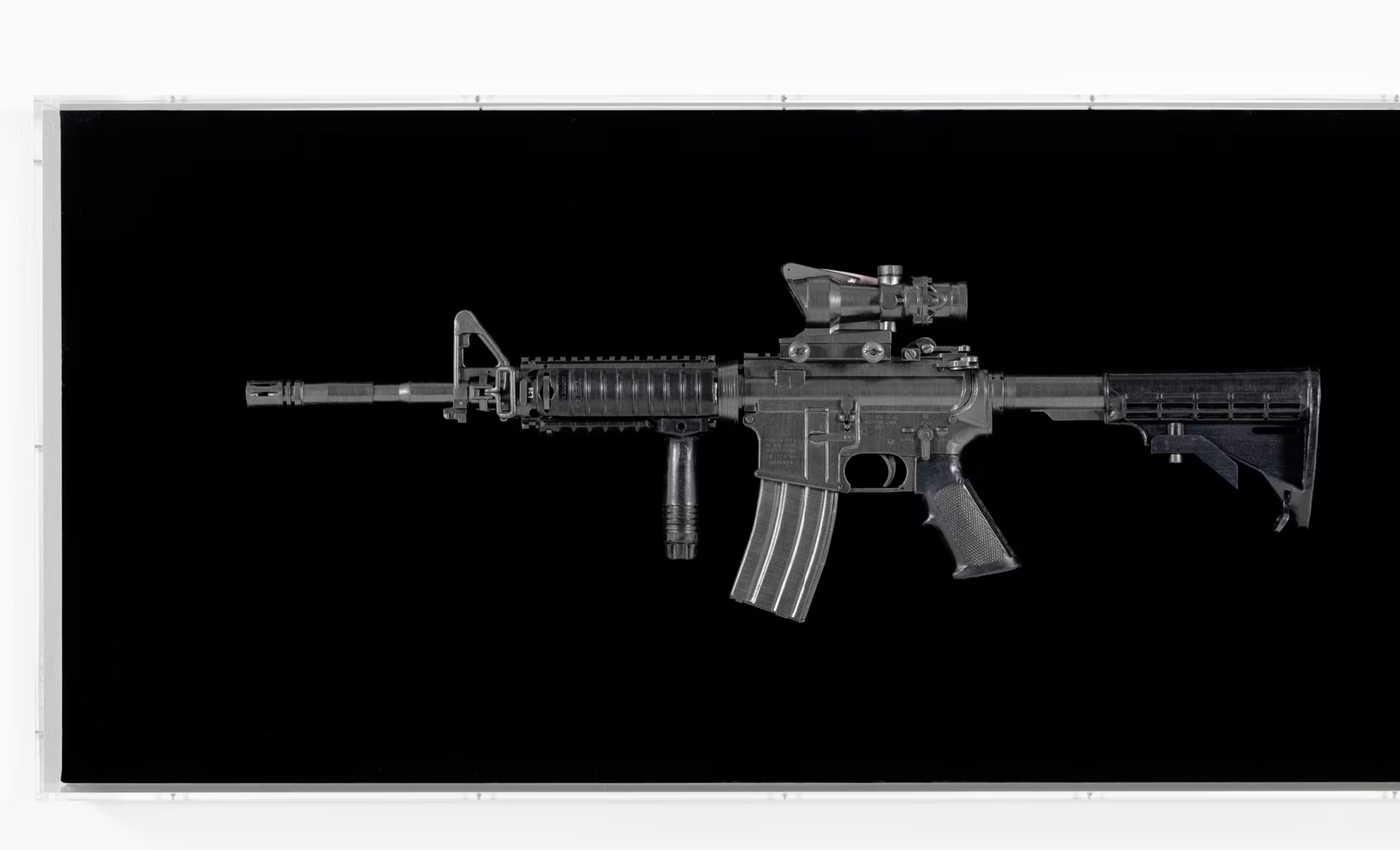

Manabu Hasegawa, M1911A1, 2014. Image courtesy of the artist and Tezukayama Gallery.

I'm eyeing a gun at the Dallas Art Fair. It’s in a glass case at Tezukayama Gallery’s booth. As I step back from examining it, a woman with perfectly coiffed white hair and a crisp pink jacket bends down to admire it. It is a model that the U.S. uses in the military—next to it is an old Japanese firearm.

“It crushes if you touch it,” gallery director Shinpei Okada says when I inquire about the sculpture by Manabu Hasegawa—it is hollow, made with paper and pencil frottage. The subject has been a recurring theme in his work for decades, and a motif that first struck him in the early ‘80s when he encountered a wounded soldier under the Ueno overpass as a child. Despite the fragile material, Hasegawa’s guns appear to be dense and loaded. It is both an object and a metaphor. “We had trouble at the airport,” she adds with a laugh.

Manabu Hasegawa, 6hk4, 2022-23. Image courtesy of the artist and Tezukayama Gallery.

All around, booths boast mostly abstract works, figurative paintings of tasteful nudes, bodies in repose within intimate spaces, plenty of flora and landscapes, and, as a friend pointed out, lots of horses. The thing about these images, devoid of offensive imagery or overt critique is that they give you space and time to fill in the blanks, or have your mind wander. And I can’t get my mind off Hasegawa's guns.

When I first arrived in town, my Uber driver greeted me by emphatically explaining why everyone is coming here. The tax cuts? A fellow writer in the backseat quipped. “No,” he replied. “Well, yes…but that’s just the cherry on top. It’s the cleanest city, these buildings are all new,” he said, gesturing to the newly minted apartment complexes as we speed past. He has been in Dallas as long as he has been in America, over three decades, and “it’s the safest,” he exclaimed—”everyone carries, so people don’t do stupid things.”

Yesterday, the Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton sued Dallas, alleging that the city's Office of Cultural Affairs banned guns at two arts venues. On Tuesday, a high school student in Dallas opened fire on his classmates—there were a total of five students injured. Last week, Texas lawmakers held a public hearing on a bill that would penalize those who prohibit handguns on government-owned land. The Dallas Museum of Art (DMA), for instance, is operated and owned by the city. The bill has yet to be voted on in the Texas Senate.

Manabu Hasegawa, 8×22mm Nambu 25 bullets, 2022. Image courtesy of the artist and Tezukayama Gallery.

Does the right to have a gun trump the right to life? Anton Chekhov once said when you introduce one into a story, it has to go off.

Texas is where art goes to live beyond its inception, upheld by a strong group of institutions, impressive private collections, and wealthy, independent collectors. It is both a cultural incubator and a political pressure cooker. But what gets lost when government censorship reaches down? What happens when police confiscate artworks, as in the recent case of the photographer Sally Mann’s nude portraits of her children at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth? Blank spots on the walls marked the absence of Mann’s work until the obscenity claim was overruled and the photographs were returned. But the aftershock remains.

Mann’s case casts a shadow on Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo’s nude lecture, which was supposed to be held at the DMA during Dallas Art Week for an audience of upwards of 300, but after Fort Worth’s reaction to the “obscenity,” the museum moved the performance to Tureen, a small gallery with a capacity a fraction of the original venue. Online, Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo (also known as Puppies Puppies) shared that Mann’s situation was used to justify her relocation.

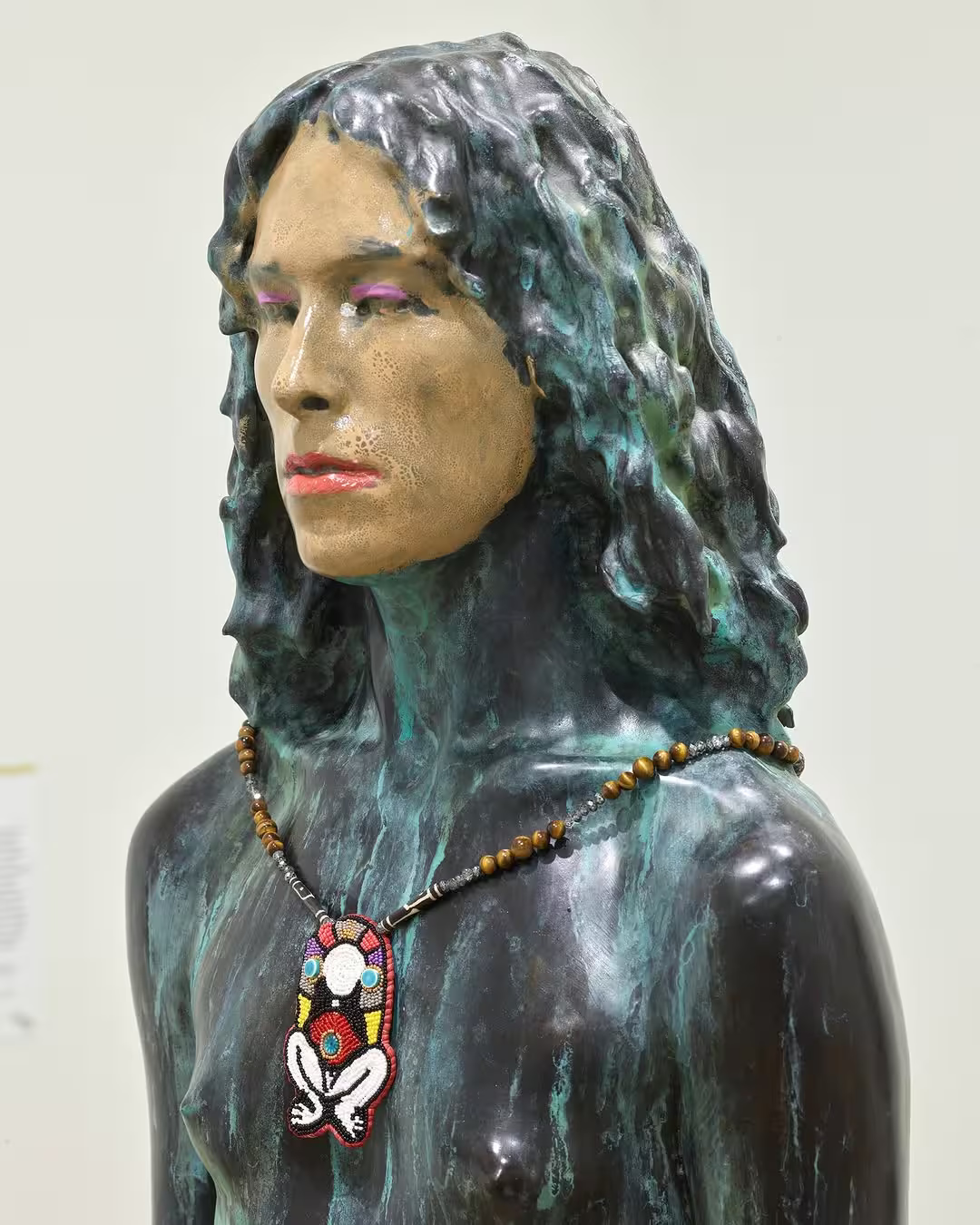

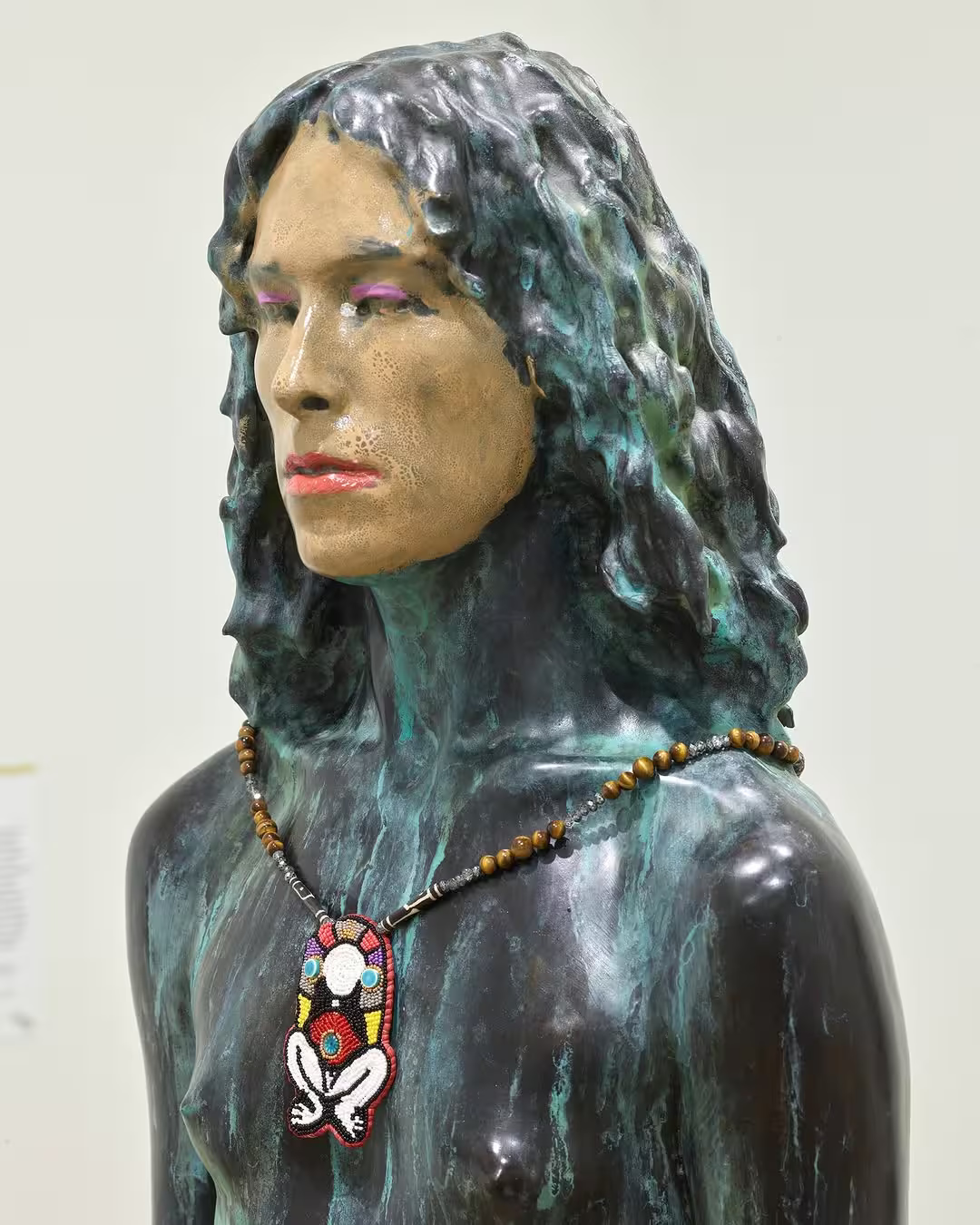

Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo), Performance with A sculpture for Trans Women A sculpture for the Non-Binary Femmes A sculpture for Two-Spirit People • I am a woman. I don’t care what you think • (Transphobia is everywhere and everyone is susceptible to enacting it at any moment) (Unlearn the transphobia brewing within) I am a Trans Women. I am a Two-Spirit Person. I am a Woman. This is for my sisters and siblings everywhere. History erased many of us but we are still here. I will fight for our rights until the day I die. Exile me and I’ll keep fighting., 2022. Photography by Brad Flowers. Image courtesy of the artist and the Dallas Museum of Art.

I’m sitting on a fold-out chair at Tureen, looking at the back of a woman’s head and crying with her as a documentary, Love, Jamie (2024), recaps her life story, or at least a part of it, the part that up until recently meant she was incarcerated on a life sentence for robbery. The part where she picks up a pen pal who encouraged and supported her art, her life, culminating in an art show in New York at Daniel Cooney Fine Art and, eventually, her parole. The film’s message is uplifting—Jamie Diaz made it out, she found a career as an artist, a chosen family—but it doesn’t skirt around the fact that to exist as a trans woman in the prison system is not easy, let alone in Texas, where a recent wave of extreme legislation targeting trans people has made headlines. Where support manifests in grassroots organizations by and for the community.

At the gallery, the front row is filled with representatives from different LGBTQIA+ nonprofits that center Texas’ transgender citizens: Resource Center, North Texas TRANSportation Network, Black Ladies in Public Health, House of Rebirth, and Texas Health Action. The documentary is a part of Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo’s programming, which marks her first time back in Dallas after 15 years away. Nearby at the DMA, a bronze, nude sculpture of her is displayed on a plinth that says “Woman,” a poignant homecoming for the Dallas native.

Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo), Performance with A sculpture for Trans Women A sculpture for the Non-Binary Femmes A sculpture for Two-Spirit People • I am a woman. I don’t care what you think • (Transphobia is everywhere and everyone is susceptible to enacting it at any moment) (Unlearn the transphobia brewing within) I am a Trans Women. I am a Two-Spirit Person. I am a Woman. This is for my sisters and siblings everywhere. History erased many of us but we are still here. I will fight for our rights until the day I die. Exile me and I’ll keep fighting., 2022. Photography by Brad Flowers. Image courtesy of the artist and the Dallas Museum of Art.

Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo undresses with the help of a friend and settles onto a mattress on the floor lit up by lime-green spotlights. A projector displays a power-point presentation above her as she begins to walk the audience through her conceptual practice. While this is billed as and has all the makings of a performance, the artist's presence feels anything but performative. Rather, she appears at home as she addresses her “sisters and siblings,” relaxed and at ease despite being fully exposed—a testament to the safe, nurturing space she has created. Outside two security guards hired by the museum pace back and forth in front of the entrance, hinting at the perpetual threat trans bodies are under. Here, art is a balm as well as a vessel for direct action. And institutional support is paramount to keeping it afloat.

I’m looking at a river six miles away at London-based Harlesden High Street's presentation at the Dallas Invitational, the smaller, independent art fair held in Rosewood Mansion on Turtle Creek. The water is rendered in strips of blue and green fleece on a panel. Its title, A Drowning Place (river), 2025, refers to the mother and her two children who drowned trying to cross the Rio Grande River from Mexico into Texas early last year.

.avif)

Antonio Lechuga, A Drowning Place (river), 2025. Image courtesy of the artist and Harlesden High Street.

“It can be seen as tragic but can be seen as hopeful,” says the artist Antonio Lechuga who made the piece last year after hearing the news. “A river is where life starts from. It feeds the crops, feeds the people. It can easily be thought of as a living place.” He pauses. “But at this moment, it is a drowning place. And if it can happen here, it can happen anywhere.”

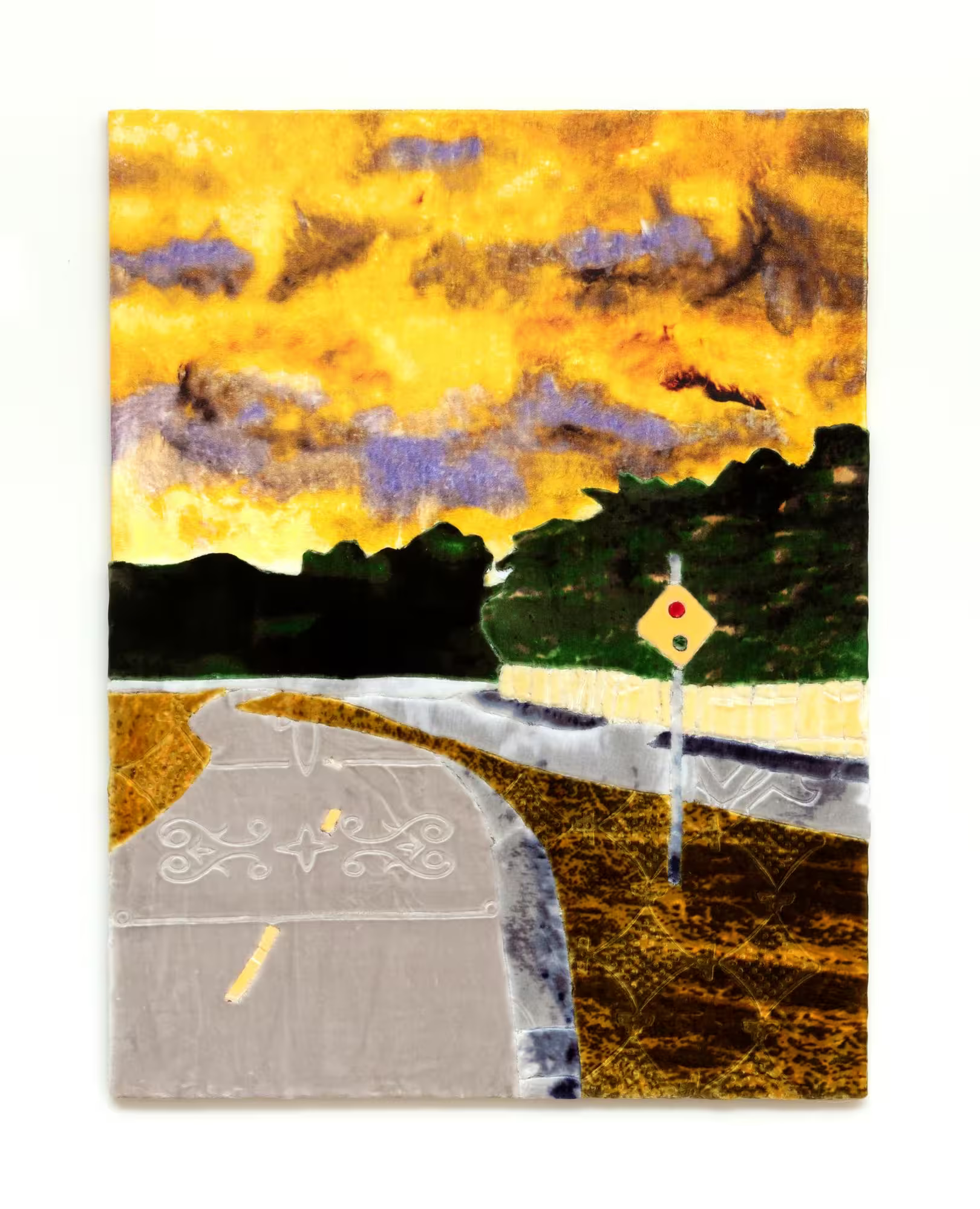

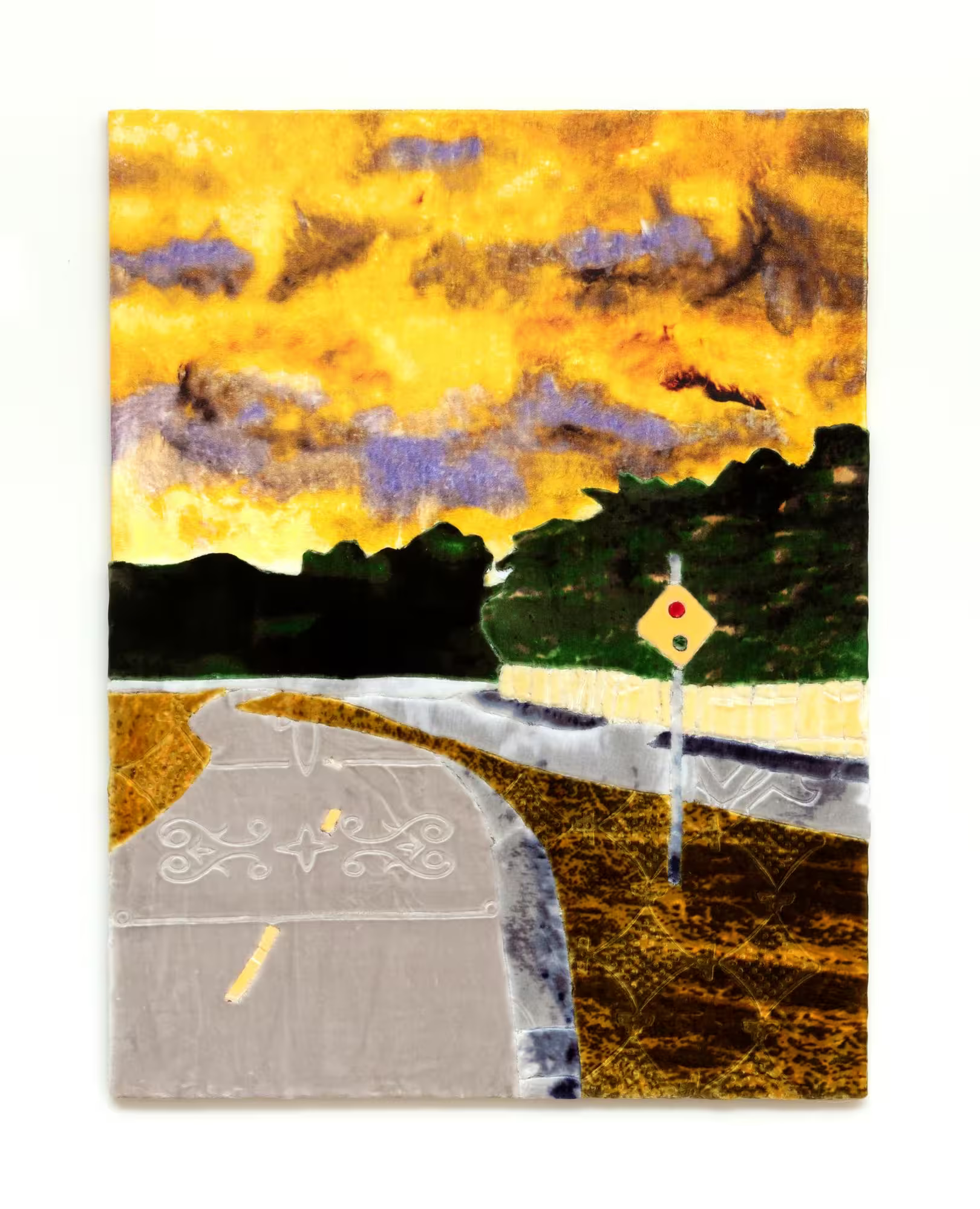

Lechuga’s works are fashioned from cut-up blankets called cobijas, found in homes of Mexican families. “They hold our lives and our stories,” explains the artist who was born and raised in Oak Cliff, a neighborhood in Dallas County. The artist’s works feature flora and fauna, but his scenes aren’t just natural sites, but also sites where something happened. In A Friday in the Summer, a Friday Like Any Other, 2024 (part of the DMA’s permanent collection), an intersection faces out into a dense forested horizon; the sky is yellow and the grass is sun-bleached. The temperature spiked over 100 degrees that afternoon in July of 2022, Lechuga recalls, and he set out to do a loop around the trail behind his studio in East Dallas—“some of the best days to run are when it’s like a sauna.” The image in his work was the last thing he saw before his life changed forever. “I was shot twice,” he tells me. “I remember everything.” He recounts the minutes leading up to the moment he was caught in gang crossfires while he was waiting to cross at an intersection. Then the months in the hospital after, the second lease on life, the anger and the action.

Antonio Lechuga, A Friday in the Summer, a Friday Like Any Other, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and the Dallas Museum of Art.

Lechuga lost a kidney and stayed in the hospital for two and a half months. Doctors were amazed he survived. He made his first piece addressing the experience soon after: An image of the intersection, the last thing he saw before he was shot, with the grassy patch he laid on in the background. Then a year later, he recreated the scene, this time as seen through a red filter, titled Everyday Since. “Before that, my whole life was different.” It was the same year when a gunman opened fire in a Uvalde elementary school, killing 21 people. “It was on my mind,” says Lechuga. So he made his series “Flowers for the Living,” in which wall panels featured a total of 637 flowers reflecting the number of people who died from mass shootings the year he was shot. “It's not just the person who was shot or killed. This bouquet of flowers is for all the people that are affected because of this, those left behind to mourn, too,” he adds.

Texas has long been in the spotlight as a place where guns are both celebrated and condemned, depending on who you ask. “But it’s not specific to Texas,” Lechuga emphasizes. “This is a national issue.” I think of Hasegawa’s pencil and paper renderings and the violence they suggest. I think of Diaz and Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo’s art that both document the experience of being trans in America while also criticizing the circumstances. I think of the right to travel, to pass through borders and spaces safely—and what happens when that right is disregarded or eclipsed by other agendas. “It’s a global issue, too,” I reply. But the stories are personal, begging the question: What do we remember, what do we forget? The answer has the potential to shift as art continues to bear witness.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)