Installation view of Diana Al-Hadid's solo presentation at Kasmin for Frieze Los Angeles, booth D6.

“I carry Syria in my heart all the time,” says Diana Al-Hadid, whose recent solo booth at Kasmin for Frieze Los Angeles recalled landscapes, including a few of her homeland. For her bronze sculpture of a spindly, bare jasmine plant, Warda II, 2024-2025, the artist dipped the national flower of Syria’s root ball in wax to make a mold. A layer of bronze seeps out from its base in what Al-Hadid reveals is a rough outline of the country.

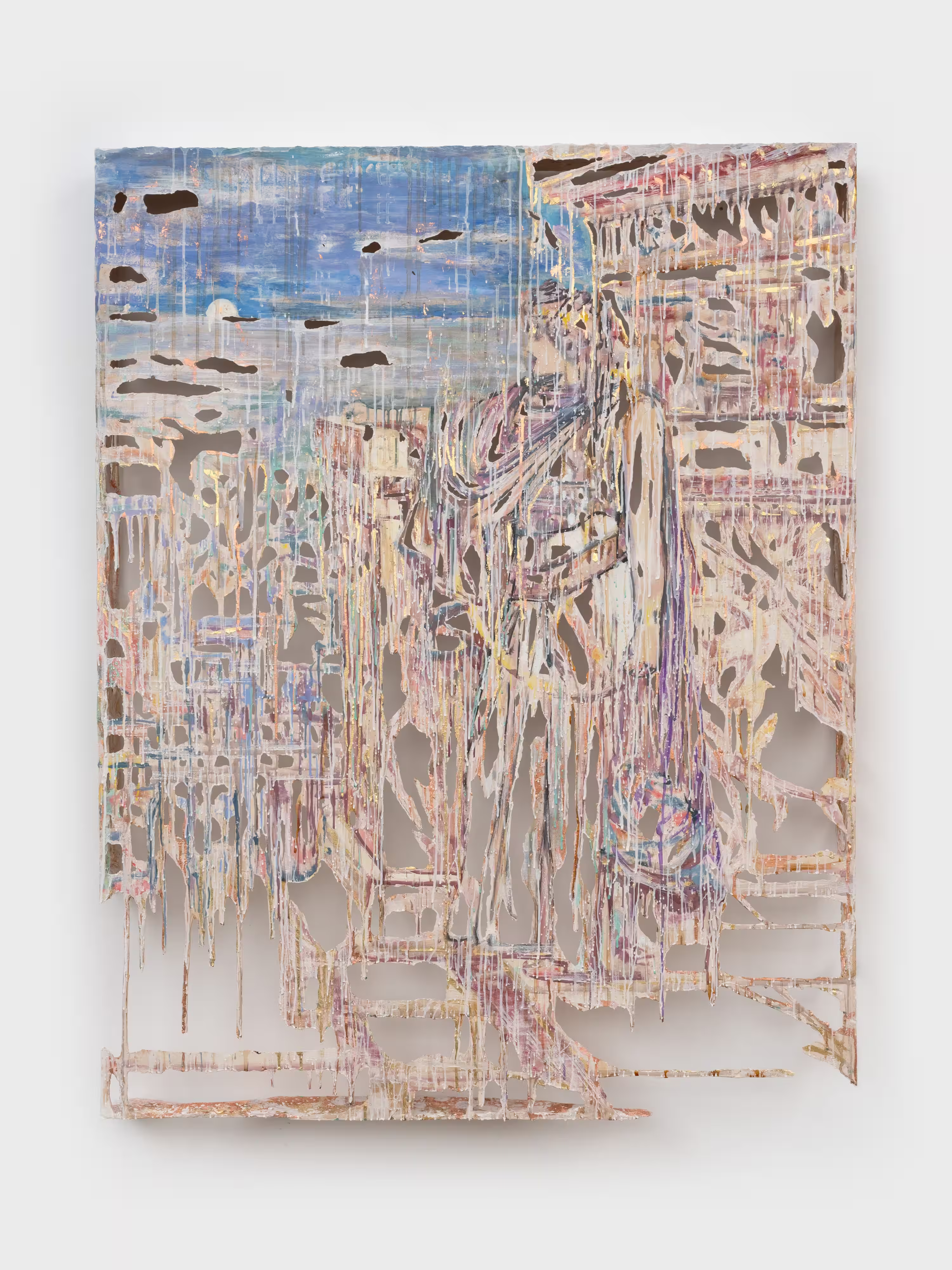

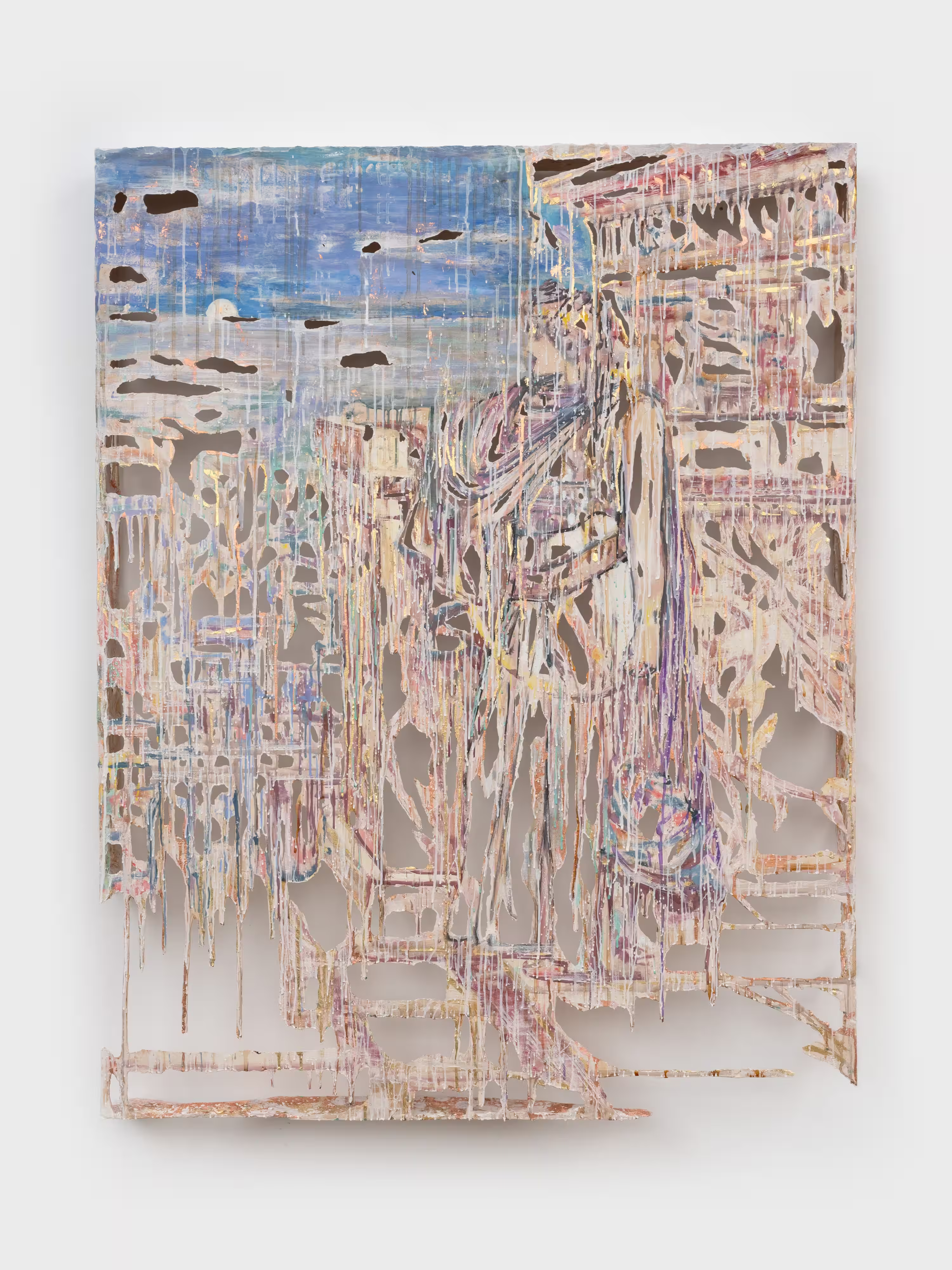

Set at dusk, Zenobia’s Moon, 2024-2025, appears as if it is decomposing or regenerating. A lattice of materials from the artist’s controlled dripping technique obscure the sky, which crystallizes in the top left hand corner. It was born from a reference to English painter Herbert Gustave Schmalz’s 1888 depiction of Zenobia, the rebellious queen of the Roman colony of Palmyra, now present-day Syria. “In the painting, she gazes at what I believe is the moon on the horizon,” says Al-Hadid.

Diana Al-Hadid, Zenobia’s Moon, 2024-2025. Image courtesy of the artist and Kasmin, New York.

Works like these reflect the time Al-Hadid spent in the mountains upstate New York after the pandemic. Pastel, threadbare depictions of skies and trees channel scenes from her property and what she describes “dramatic, impossible perspectives interpreted from 16th- and 17th-century Dutch paintings,” like those of Pieter Bruegel. While Al-Hadid was working on one such wall panel, Dear Wife, Save Me, 2024-2025, she looked at Bruegel’s Magpie on the Gallows, 1568. “Upon his death he asked his wife to burn a lot of his work but said she could keep this one for herself,” she says of her affinity toward the painting. “I was curious as to why he wanted to give her this particular work. I love weird gestures of love,” she adds.

History and speculation, imagination and logic are two sides of the same coin for the artist—dualities that allow for nuanced interrogation of how we understand meaning. As a child, the artist’s older brother would tell her bedtime stories about worlds made of bubbles. “I still think about that world,” she admits.The artist, whose family immigrated from Aleppo, Syria to Cleveland, Ohio when she was 5 years old, recalls watching the city release over a million helium balloons into the sky a few months after her arrival. “I had been in the country no more than a couple of months but I distinctly remember this,” she says. “It was this grand, happy gesture—something outrageous and oversized, a quintessential American experience.”

Diana Al-Hadid, Dear Wife, Save Me, 2024-2025. Image courtesy of the artist and Kasmin, New York.

At home Al-Hadid learned Islamic folklore, and in school Greek mythology. The story of the minotaur in the labyrinth in particular resonated with her: it tells the story of a hero who uses a ball of yarn to escape the labyrinth and kill the Minotaur. “I love debate, and so I was really drawn to the metaphor, in which logic is a method of problem-solving by exhausting all avenues of thought,” she says. Today, such mazes unravel in her works, revealing her complex web of references.

Throughout her practice, in which historical and personal context is transmuted into ethereal, thickly layered labyrinths, Al-Hadid probes constructions of femininity and gendered agency via mythological stories of women in captivity, as well as how feminine power is depicted in mythology in general. “I like to catalog all the various ways in which women are cloistered, held in towers, mountains, walls even,” she explains. “Often these imprisonments are by powerful men to prevent a prophecy that will challenge their authority from coming to light.” That today these tropes feel extra prescient goes without saying: “How quickly the public will turn on a woman for speaking up against abuse, especially if they don’t match up to our notion of the perfect Disney victim,” Al-Hadid observes. “How often women are pressured to prioritize or adapt to the needs of men.”

Diana Al-Hadid in her studio. Photography by Charlie Rubin. Image courtesy of the artist and Kasmin, New York.

This year she has two upcoming projects at the MSU Broad Art Museum and Princeton University Art Museum. The former, opening in June, will feature works from the past two decades that connect her process of reworking materials to reworking frameworks around womanhood. The latter is inspired by the university’s expansive global collections including objects from her birthplace of Syria, to Turkey, to the ancient Eastern Mediterranean. Is there a project she has yet to realize? “So many ideas,” she says. “So little time.”

.avif)