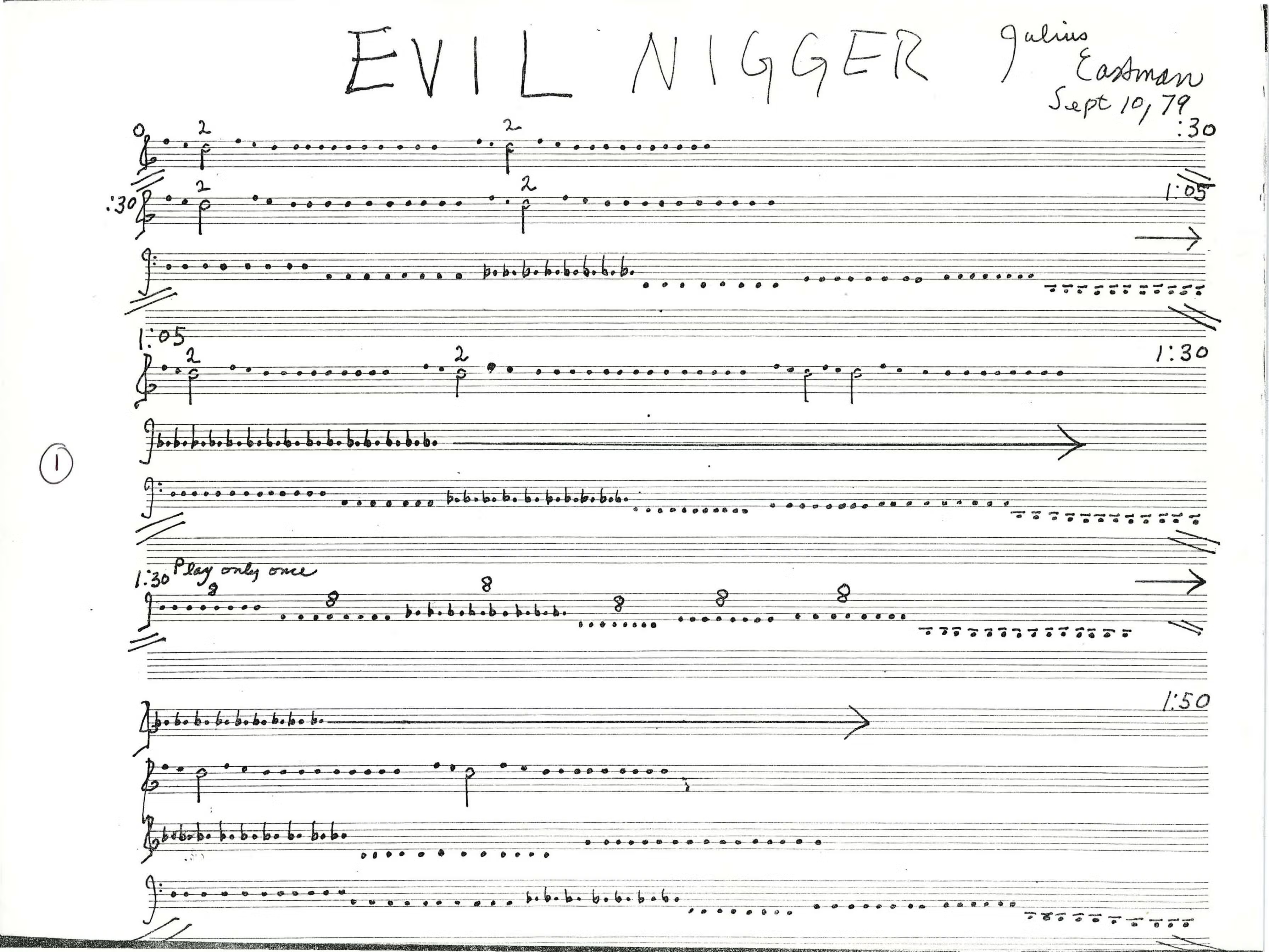

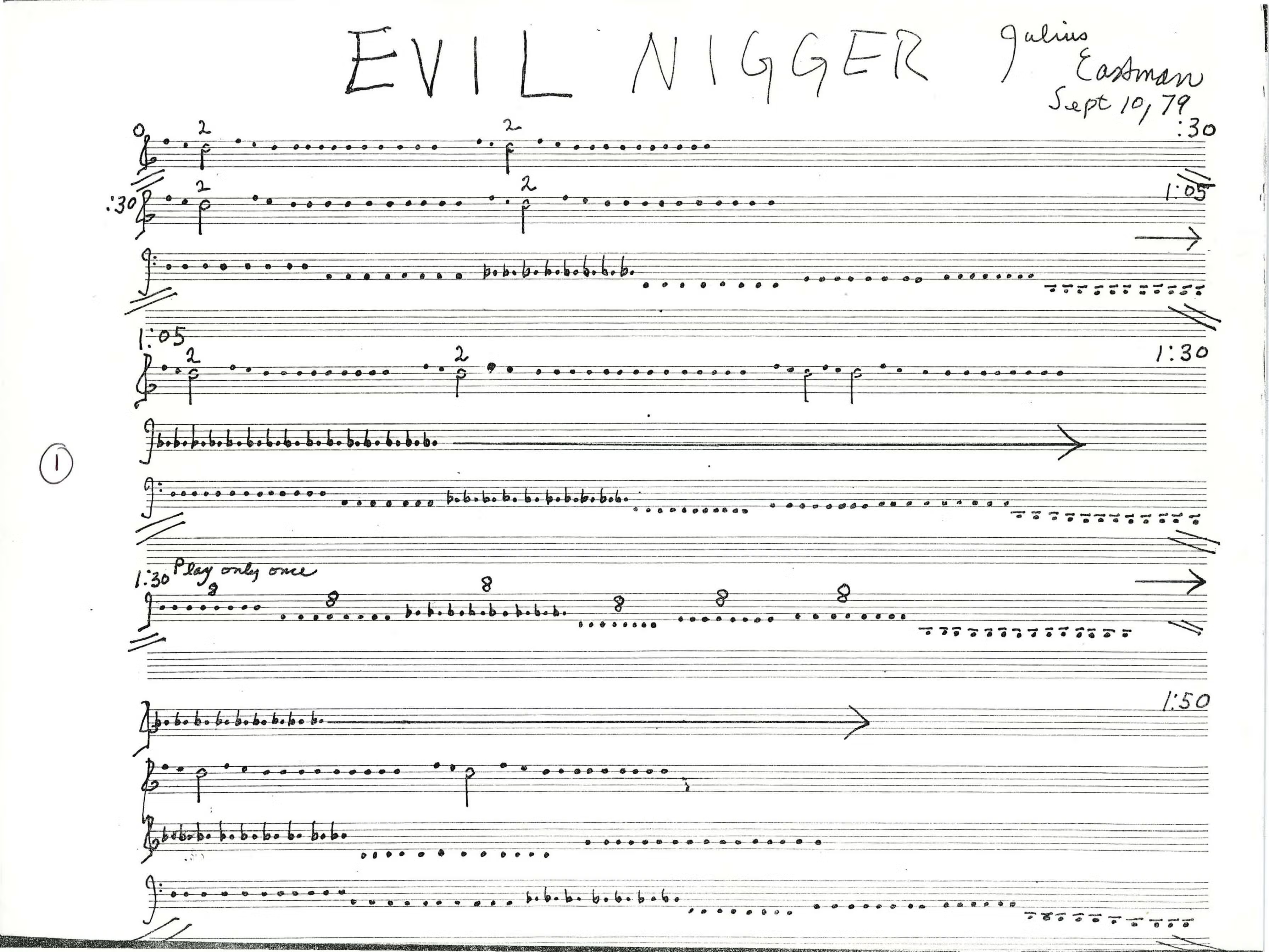

Julius Eastman, Evil Nigger, 1979. Copyright © 2018 by Music Sales Corporation (ASCAP) and Eastman Music Publishing Co. Image courtesy of ASCAP.

“What do you think of when you see the title ‘Evil Nigger’?” I’m asked as I walk into 52 Walker in New York. The words are emblazoned in all caps on the cover of a new zine inside the gallery at the start of its new, two-person exhibition, Julius Eastman & Glenn Ligon: "Evil Nigger.”

I smile now thinking of the late Pope.L’s 2002 book Hole Theory and the connections Eastman would have probably had with it given his “The Nigger Series,” a seminal collection of works recorded around 1980. I can only imagine that Pope.L’s very response to this question might be found in his own writing: “How is one to decide how to be right within the lack of the world?”

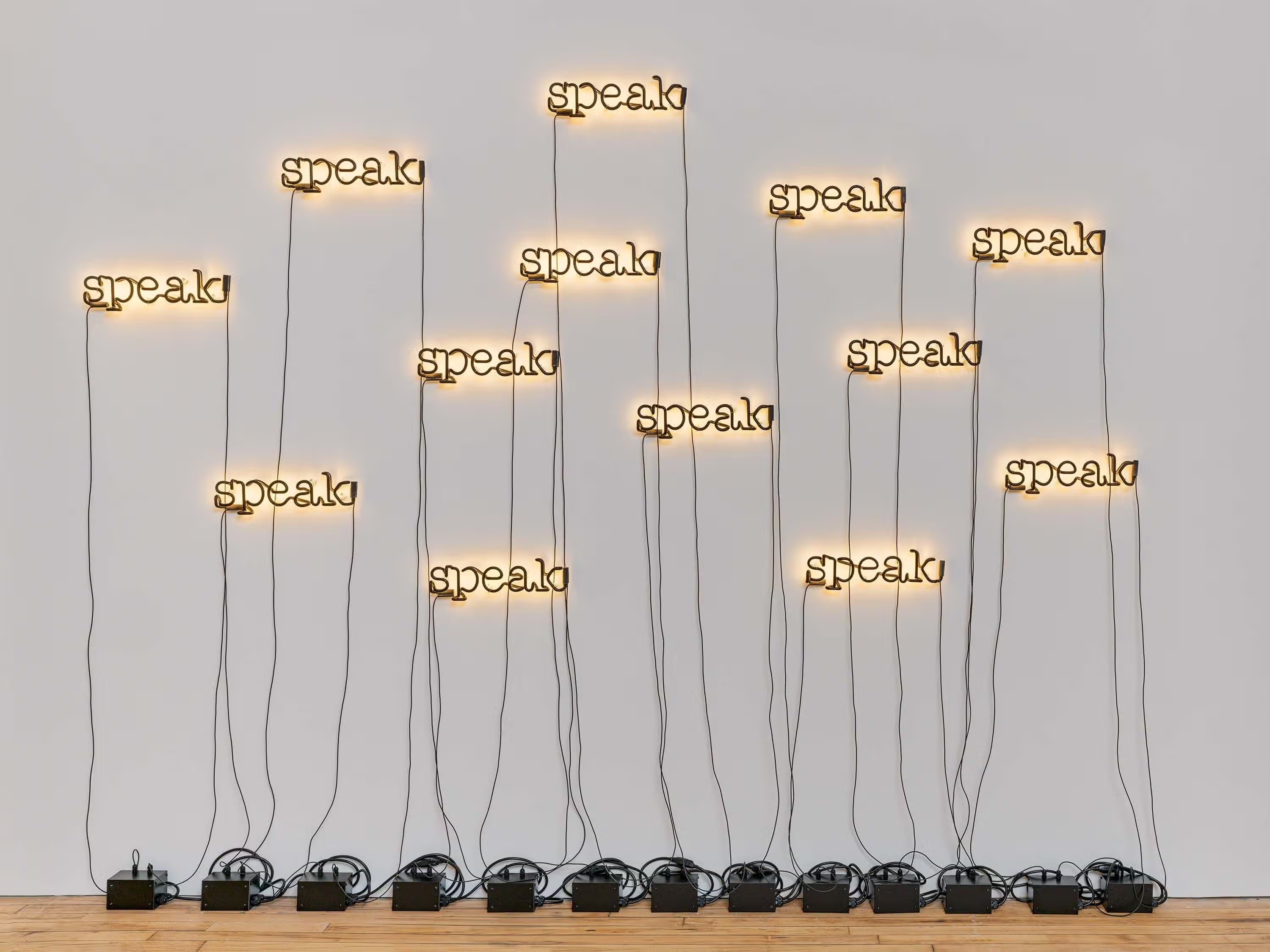

Installation view of Julius Eastman & Glenn Ligon: "Evil Nigger." Image courtesy of 52 Walker.

Throughout his life, Eastman pushed past the societal limits imagined for Black Americans. The post-minimalist composer and musician from New York had created at least 15 scores by 1970 when he joined composer Petr Kotik’s S.E.M. Ensemble. Two years later, he made his New York Philharmonic debut. Eastman would later cement his reputation as a provocateur when he performed three major compositions in 1980—titled “Evil Nigger,” “Crazy Nigger,” and “Gay Guerrilla”—at Northwestern University in Illinois. The same year, Eastman infamously had all his possessions harrowingly destroyed by the NYPD Housing Authority in the Lower East Side. In the decade that followed, he showcased a relentless commitment to music, which challenged both sonic and social structures before passing away in 1990, homeless, at the age of 49. Today Eastman’s compositions, although not many, remain incredibly powerful.

As I listen to Eastman’s music emitting from self-playing pianos at 52 Walker, something arises from within me. When positioned next to new works by Ligon, another dimension of conducting becomes more clear. It’s a cross-generational dialogue anchored to Eastman’s aforementioned “The Nigger Series.” Says 52 Walker director, Ebony L. Haynes: “I was interested in curating something about notation, authorial voice, minimalism, translation, context. I was really thinking about the person who was creating that language and writing that score.”

Glenn Ligon, Untitled (America) (for Toni Morrison), 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and 52 Walker.

Haynes’ exhibition begins with Eastman’s “Evil Nigger,” 1979, a compositional work grounding the viewer, but the curator makes it clear this show is not only about sound. Ligon’s standing neon work, Untitled (America) (for Toni Morrison), 2024, spells out “sth tsh sth,” a common teeth-sucking sound amongst African diasporas, one that can be interpreted as an audible disapproval or dismissal through the action of the tongue swiftly pulling air against the teeth. The neon’s spelling is illustrated in Toni Morrison’s handwriting, positioned across from the four pianos almost as if it is conducting Eastman’s sheet music.

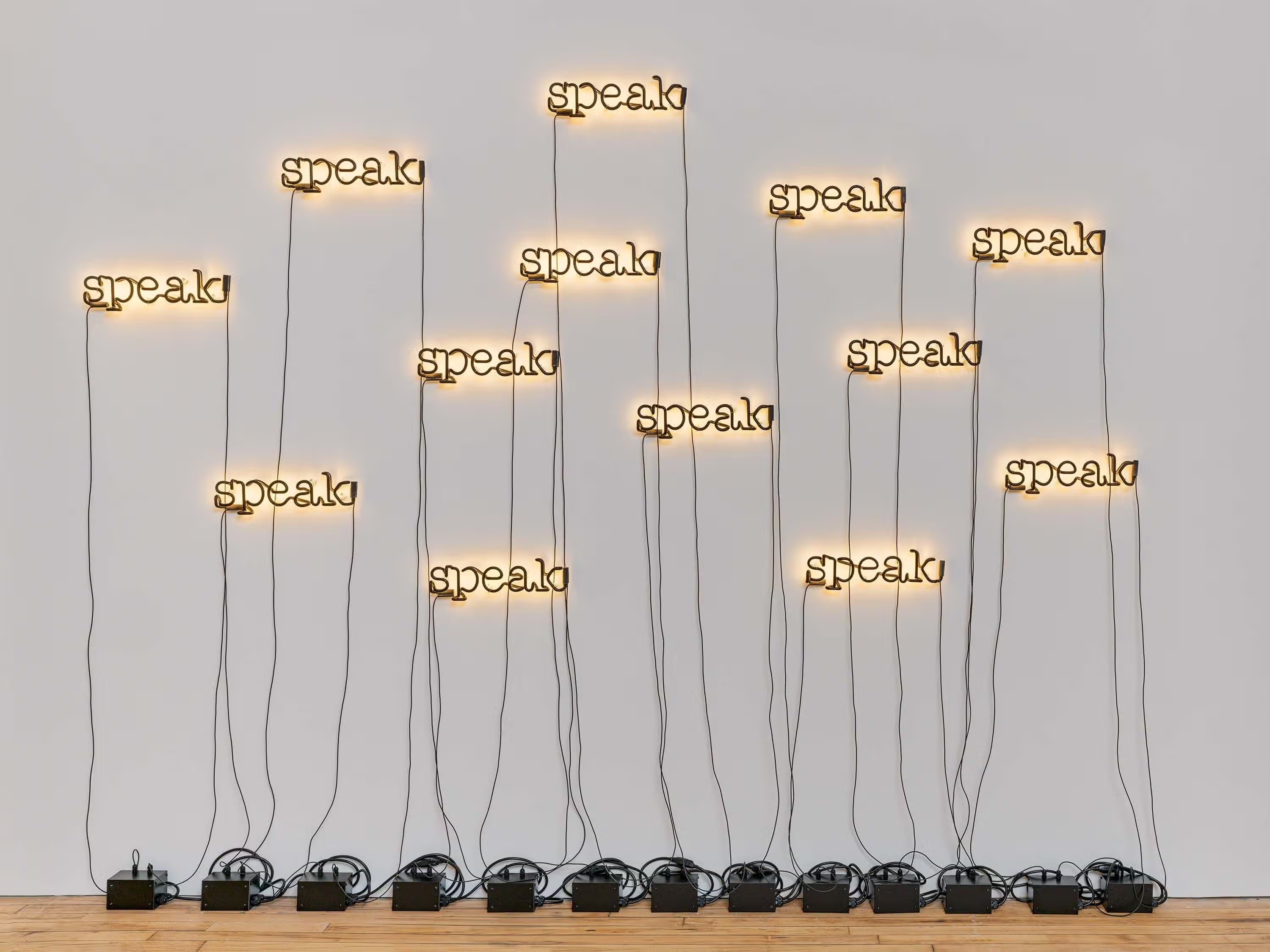

Another neon, Sparse Shouts (for Julius Eastman), 2024, references the composer’s prayer-like a cappella interlude to his score “The Holy Presence of Joan d’Arc.” There is a section in Eastman’s original piece in which he repeats the word “speak” 13 times. Ligon’s animation blinks off and on, corresponding to the recording of Eastman singing the song. “I first became aware of Julius through musicians and thinkers like Jace Clayton and Okwui Enwezor,” explains Ligon, crediting the latter for exposing him to Eastman’s work firsthand in 2015. “He curated the Venice Biennale, where the Arena featured Eastman’s compositions,” he recalls.

Glenn Ligon, Sparse Shouts (for Julius Eastman), 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and 52 Walker.

The exceptional thematic and conceptual similarities between the two men is apparent throughout the show. Both artists engaged in themes of identity, language, and the rejection of mainstream norms, evident in the fact this is the first U.S. showing of Eastman’s works. Ligon is now widely recognized and celebrated, but his work didn’t always get the institutional recognition it deserved. This pairing poignantly draws connections between both queer men as they confront uncomfortable truths. While Ligon’s work doesn’t usually deal with sound and voice directly, his decision to engage with Eastman’s music was a pointed one. “For queer people and for Black people, the idea of coming to voice and the many ways that can happen is so important,” says the artist.

“Julius Eastman & Glenn Ligon: Evil Nigger” is on view until March 22 at 52 Walker at 52 Walker Street New York, New York, 10013.

.avif)