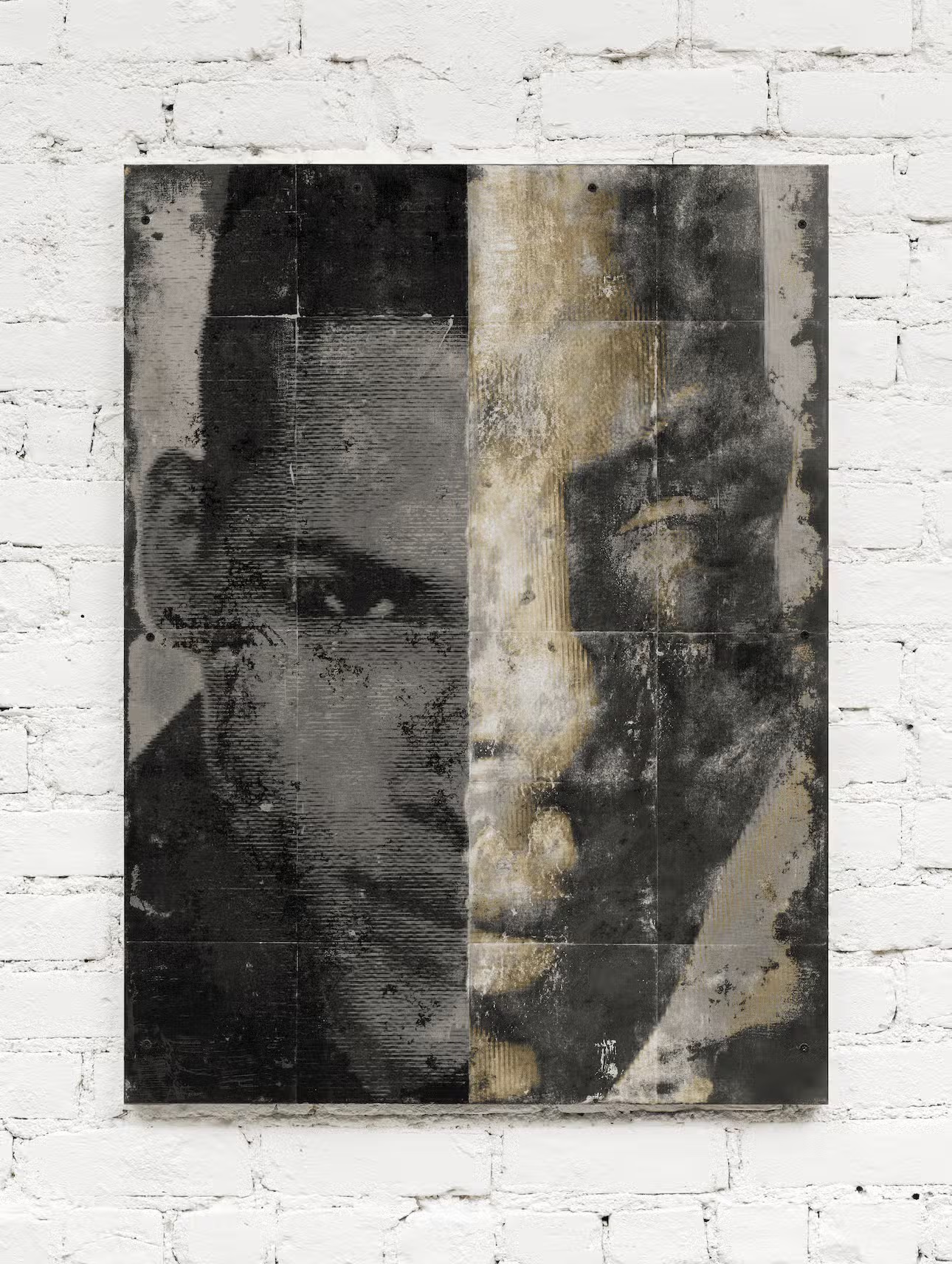

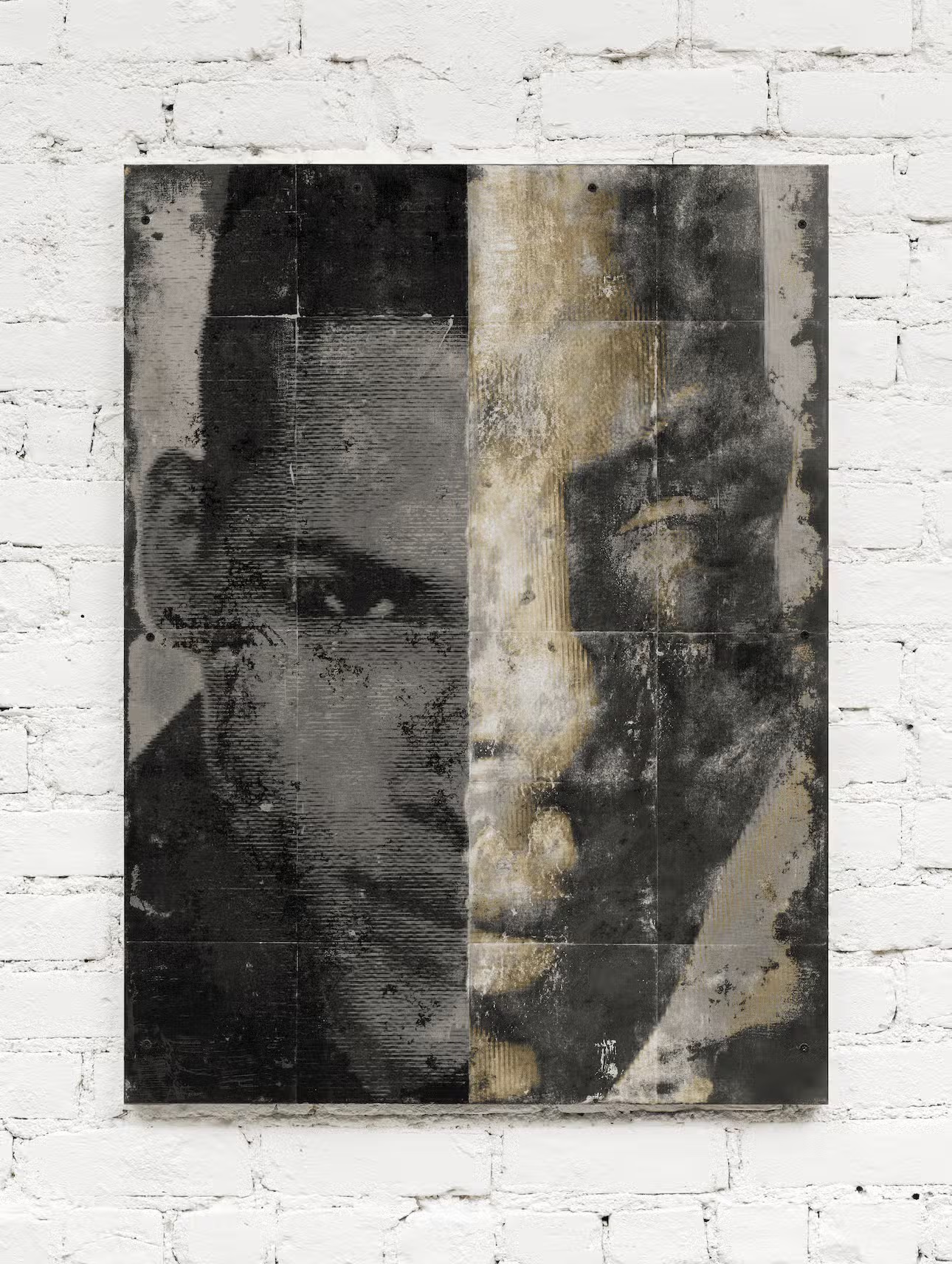

James Bantone, 1312348(Jeunesse), 2024. Photography by On White Wall. Image courtesy of the artist and New York Life Gallery.

James Bantone takes up the quintessential all-American medium, steel for his second solo U.S. exhibition, “Scrap,” following the Paris-based artist's show with the Swiss Institute last spring. Bantone transforms slabs of this industrial material, synonymous with strength, resilience, and mass production, into sleek artworks. The works aren’t humongous minimalist excretions or rhizomatic-cloud capitalism installations. Rather, they are faux-photographs: steel slabs overlain with collaged images of undressed mannequins and portraits of the real-life human models the mannequins take after. Clothes always seem to impose context, whereas the naked skin and surfaces in Bantone’s images reveal what’s underneath. Perfectly imperfect, the exhibition runs until the end of this month at Ethan James Green’s gallery named after the New York Life insurance company, whose fluorescent, cyan-blue sign illuminates the street beyond.

To make the 15 artworks in “Scrap,” Bantone found sheets of tossed-out stainless steel—unforgiving, reflective, and steeped in modernist aspirations—and embeds them with black, white, and blood-red image transfers of mannequins and models sourced from vintage fashion wholesale catalogs. Once sourced, he Xeroxes and prints them onto laser-ink paper. Some of the images he purposefully inverts so that light tones go dark and dark tones shine light. Then he transfers his eusexual subjects (or objects) and distresses them. Using heat, chemical, and vinegar treatments, as well as hand-made scratches, he alters the material so his mannequins and models, really, one supposes, his muses, look aged, discolored from the chemicals and vinegar treatment which expel a thin, rainbow-y film across the slabs. It's a very Gotham patina. Defective. It recalls the oil-ringed puddles that decorate the city’s overused streets complete with garment-wearing mannequins dripping in H&M x Mugler sweatsuits behind storefront window displays. I’m tempted to try to grab at these tattered art-advertisements during the show’s opening but you shouldn’t mug the muse.

James Bantone in the studio. Photography by Jan Anthonio Diaz. Image courtesy of the artist and New York Life Gallery.

“Scrap” stages its own existential wager: In a gallery named for an insurance giant selling security and longevity, the artist’s panels perform a sly eulogy for permanence, composed of hauntifacts with tarnished, spectral surfaces mocking the impossible dream of every artist, that of timelessness. Fashion fades, but beauty is eternal. Yet here, beauty is shown to thrive in imperfection, in decay, and in the fleeting after-image of something once whole.

It makes sense that the artist started off in photography, a practice steeped in after-images. He went on to study video as an undergrad at the Zurich University of the Arts in 2019 followed by a master’s in contemporary art at the Geneva University of Art and Design in 2021. In the last four years, he’s shown extensively across Europe, developing his signature style which includes saturated photographs of highly stylized barbershop hairstyles on friends, ill-fitting business attire on unrecognizably Photoshopped models, and enigmatic neoprene- and safety pin-covered black figures reminiscent of Cy Gavin’s painted subjects.

Installation view: "James Bantone: Scrap" at New York Life Gallery. Photography by On White Wall. Image courtesy of the artist and New York Life Gallery.

The artist often describes the neoprene- and safety pin-covered recurring figure—his alter ego, inspired by cartoon supervillains like HIM from The Powerpuff Girls and other pop culture mischievous spirits embodying both camp and menace—as a stand-in for himself. Sometimes the figures wear a mask of Bantone’s face. In his installation, Terminal Irony presented at Karma International Gallery in 2021, a headless, jet-black and emerald-stained figure struggling to free itself from a mirror pushes this idea further into terminal irony, in which he cannot even see himself morphing to the subject of the other’s gaze. Lacanian or Freudian, all this froufrou gazing theory is making me dizzy.

At New York Life Gallery, three bisected portraits of male models—titled after their respective mannequin’s serial numbers, S29D, S30G, and S28P, 2024—speak to Bantone’s continued reflection on capturing timelessness, albeit there’s still an uncomfortable dissonance between identification and depersonalization he encourages us to recognize. One male model with swooped hair and wide-open, almond eyes appears mid-exclamation, but his tone is inscrutable. The artist has sliced the man’s face in half and replaced his nose, mouth, and chin with that of a cheerful mannequin. His new lower face comes with a peculiar, affected smile. The smirk harks back to similar mannequin-inspired artworks shown in downtown New York over a decade ago, like those by Telfar Clemens, Cajsa von Zeipel, and Stewart Uoo, who’ve often played with similar themes between the idealized yet commodified human form and its flesh and bone human inspiration. Both Clemens’ and von Zeipel’s mannequin sculptures tend to resemble their makers but Bantone’s facial features are not obvious in any of his faux photographs; rather, his fragmented compositions evoke a sense of anonymity. There are different ways to interpret this distortion. What I see are exaggerated fashion victims.

James Bantone, S28P, 2024. Photography by On White Wall. Image courtesy of the artist and New York Life Gallery.

Bantone’s faux photographs confuse human faces with the artificial precision of mannequins. Their distressed surfaces—blemished and bruised, stained and corroded—embody the latent hostility between permanence and decay. A few of the steel panels show mannequins in sectioned-off, full-body units, Unit (Man 1), 2024, and Unit (Man 2 & 3), 2024, like an anatomy poster in a physician’s room, or in contrapposto, Untitled, 2024, alluding to art historical underdogs-as-subjects like Michelangelo's David or Polykleitos's Doryphoros. Others are praying, “kneeling, headless; their heads have been chopped off by their makers. It has to do with the idea of submission and the loss of agency,” Bantone explains.

The artworks, diverging from the polished realism of mannequins in window displays or on runways, resemble relics salvaged from the trappings of fantasy. They come with visible red glamour wounds and psychic scars, equating identity not with the contemporary notion that representation is the human body authentically portrayed but rather identity in the 21st century is the human body under emergency, being cut open on a physician’s gurney, rendered into an idealized object by an artist, or asking for penance or a miracle from a king or a god. The choice of steel then might be Bantone offering this versatile material as a structural element of support for the human body under emergency.

James Bantone, Unit (Man 1), 2024. Photography by On White Wall. Image courtesy of the artist and New York Life Gallery.

Art has always served as a medium for communication across time—a wager on a future audience with curious eyes, an endeavor to inscribe beauty and its inseparable companion, truth, into something priceless and timeless. However, commodification challenges this aspiration, especially in situ in the rotten Big Apple. Bantone's mannequins and models underscores this tension, suggesting that while identity may be idealized yet commodified, the deeper essence of beauty and truth strives for permanence beyond whatever it is that is contemporary. These days, the emergency seems to be replacing the contemporary. Fashion fades, will beauty soon follow suit?

"Scrap" is on view until January 25th, 2025 at New York Life Gallery 167 Canal Street Floor 5, New York, NY, 10013.

.avif)