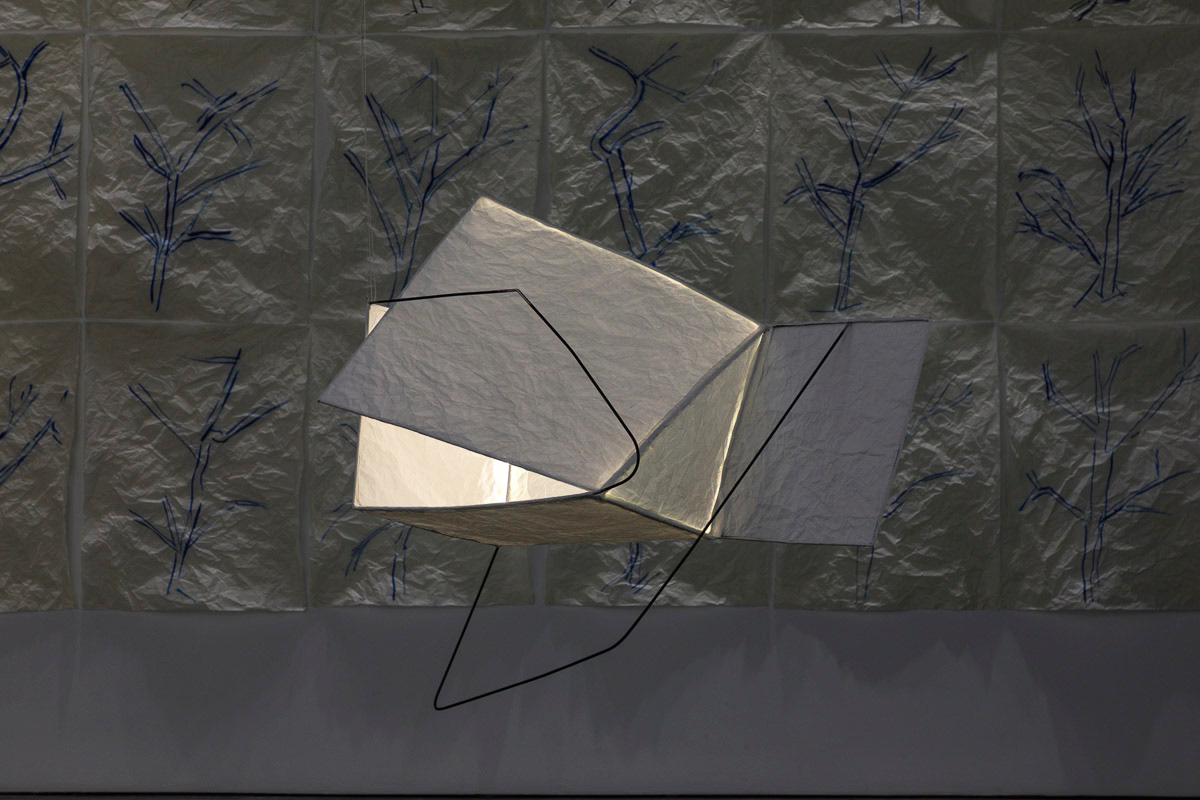

Installation view of "Joan Jonas: Empty Rooms.” Copyright of the artist and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photography by David Regen. Image courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

Most mornings for Joan Jonas begin with walking her poodle, Ozu, returning to her loft on Mercer Street, where she has lived and worked for over six decades, and having breakfast. A collector of odd and unassuming things, her home is filled with relics and curiosities that inspire her: drawings and notebooks sprawled across tables, stacks of books, numerous mirrors, time-worn masks, sun-bleached kites, several bird-callers, collected stones, and wooden animal figurines.

At 88, Jonas has outlived many of her closest friends—collaborators like choreographer Trisha Brown, whose mentorship informed Jonas’ radical approach to movement, and sculptor Richard Serra, with whom she traveled to Japan in 1970, returning with the Sony Portapak camera that forever changed her practice. Others, like Susan Howe, remain. At the opening of Jonas’ “Empty Rooms” at Gladstone Gallery, the poet read a series of her works.

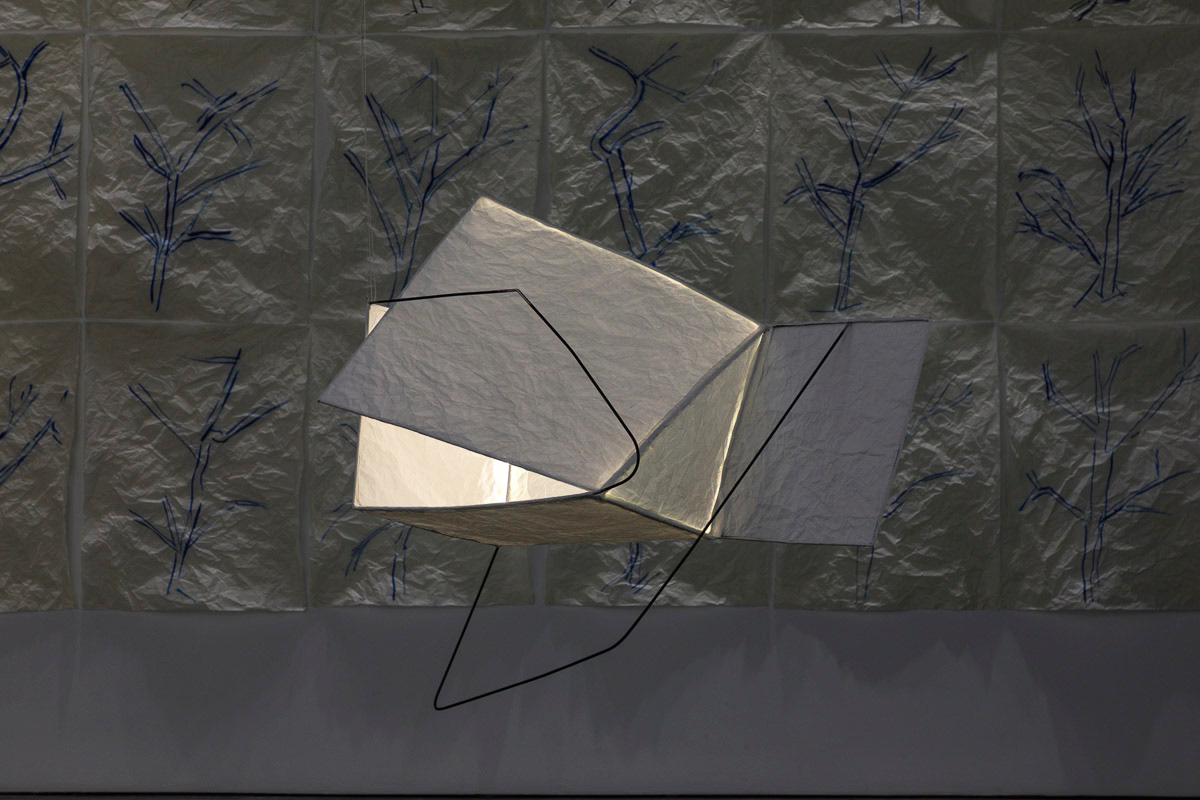

Installation view of "Joan Jonas: Empty Rooms.” Copyright of the artist and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photography by David Regen. Image courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

Central to the exhibition, which invites viewers to contemplate what lingers in the spaces left behind, are 12 hanging sculptures crafted from Japanese Torinoko paper and sewn onto steel wire frames, each inspired by a friend Jonas lost last spring. “It was something I couldn’t shake off,” Jonas says of what became the exhibition title. “The idea that a room was left empty.”

The artist doesn’t attempt to resolve absence nor does she treat it as something finite. Instead, her work moves through the murky space between remembering and forgetting, where the past refuses to stay still. At the gallery, it hovers overhead, suspended in aerial vessels, at once delicate and unyielding. After all, an empty room isn’t really empty—light shifts, air moves, dust unsettles. But the installation is not to be conflated with grieving; Jonas mourned before making, and as always, leaves meaning open-ended. “Everyone will see it in their own way; I have no control over that, and I don’t want to,” she says, her short, silvery locks framing her inquisitive gaze.

Installation view of "Joan Jonas: Empty Rooms.” Copyright of the artist and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photography by David Regen. Image courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

Jonas’ presence holds the weight of a lifetime spent observing, her voice steady and precise, each word carefully paced. The artist’s work has always moved fluidly across mediums—poetry, performance, video, drawing, sculpture and installation—each folding into the next. When she saw Mirror Piece I & II, 1969, restaged at the Museum of Modern Art last June (to accompany her first retrospective in her hometown), she was struck by its iterations. “They performed it ten times,” she says of the work in which performers carry mirrors and panes of plexiglass in synchronized motions, reflecting and fragmenting their surroundings as the piece unfolds. “But I didn’t think of it as ritual when I made it.” Watching it again made her reconsider.

“Empty Rooms” is an open-ended environment without a fixed viewpoint. Visitors move around, assembling the narrative from fragments—the floating structures, ink drawings of trees on handmade paper, outsider folk art, an original piano composition by longtime collaborator Jason Moran, and a projected video. Recurrence runs throughout: the same lines traced again and again, shifting across mediums. Jonas has always worked in loops—gestures revisited, ideas resurfaced, the past bleeding into the present.

Installation view of “Joan Jonas: Empty Rooms.” Copyright of the artist and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photography by David Regen. Image courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

The footage and the whale—an artwork by Myles Kehoe—come from Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, where Jonas has spent summers since 1970. A version of this imagery was first presented in “They Come to Us Without a Word,” her 2015 U.S. Pavilion installation at the Venice Biennale. There, the sequence meditated on disappearance, both ecological and metaphysical, blending ghost stories from the island with images of bees, birds, wordless children and teens, and the artist herself, masked, drawing on a chalkboard with ritual-like motions. In “Empty Rooms,” the video reappears as a shadow, its presence reframed to feel at home within this new constellation of works. Nature has been integral to Jonas’ work since early pieces like Wind, 1968, where she filmed performers struggling to move against powerful gusts on a Long Island beach. The act of returning—to concepts, to materials, to spaces both physical and symbolic—underscores the cyclical nature of her practice, not as mere repetition, but as an evolving dialogue with form, memory, and perception.

Jonas’ experimental approach to space traces back to childhood visits to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where the Egyptian collection of miniature sculptures sparked her imagination. At MoMA, Paul Cézanne’s The Bather, 1885, also left a lasting impression. “It was the first thing you saw when you walked into a certain room,” she remembers of the painting that pushes foreground and background together, effectively rupturing perspective. Jonas became attuned to how a work could heighten the viewer’s sensitivity to composition, distance, and their own vantage point simply by its placement—a spatial awareness that informs her installations.

Installation view of “Joan Jonas: Empty Rooms.” Copyright of the artist and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photography by David Regen. Image courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

The artist’s interest in place, in setting roots, has remained constant. Jonas came of age in a New York that no longer exists, a late ‘60s downtown where structures were falling apart, where possibilities emerged in the cracks. Today, she still lives in the very same loft where she first staged performances, where she and her peers intermingled, where ideas were shared as freely as space.

Since then, Jonas has been reckoning with time—how it erodes and accumulates, how it fractures memory yet leaves imprints behind, how it shapes what we see and what we remember. But she doesn’t dwell, nor does she rush. She moves with measured intent, allowing the next idea to surface on its own. When asked if there’s a project she has yet to realize, Jonas answers, “Not yet,” with the nonchalance of someone who knows better than to waste time chewing on such questions.

“Empty Rooms” is on view through April 12, 2025 at Gladstone Gallery at 530 West 21st Street, New York, NY 10011.

.avif)