Martina Cox, Spinal Top, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Alyssa Davis Gallery.

“Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity,” wrote the philosopher and mystic Simone Weil in a letter to the poet Joë Bousquet. I’m often reminded of this line when observing the work of an artist whom I’m pointedly drawn to. It’s touching to encounter the labored research and obsessive tendencies of another’s mind, to discern the vital expressions of their thinking through tangible, visual objects—as well as the compulsion to share these findings with others. And for those who do this particularly well—that is, get the point across—it’s a way of shortening the gap of relation between maker and viewer, broadening ways of seeing, arousing the veritable wellspring of human connection.

Attention, then, remains a core conviction of the work of artist Martina Cox. Dealing primarily with antique Victorian garments (which she prodigiously researches and collects on online bidding sites), Cox is interested in the architectural structuring of these pieces, and the history and gendered customs that have since come about. More than that, the work is an exacting attention paid to what these garments obscure and the secrets and hidden labors their fabric contains.

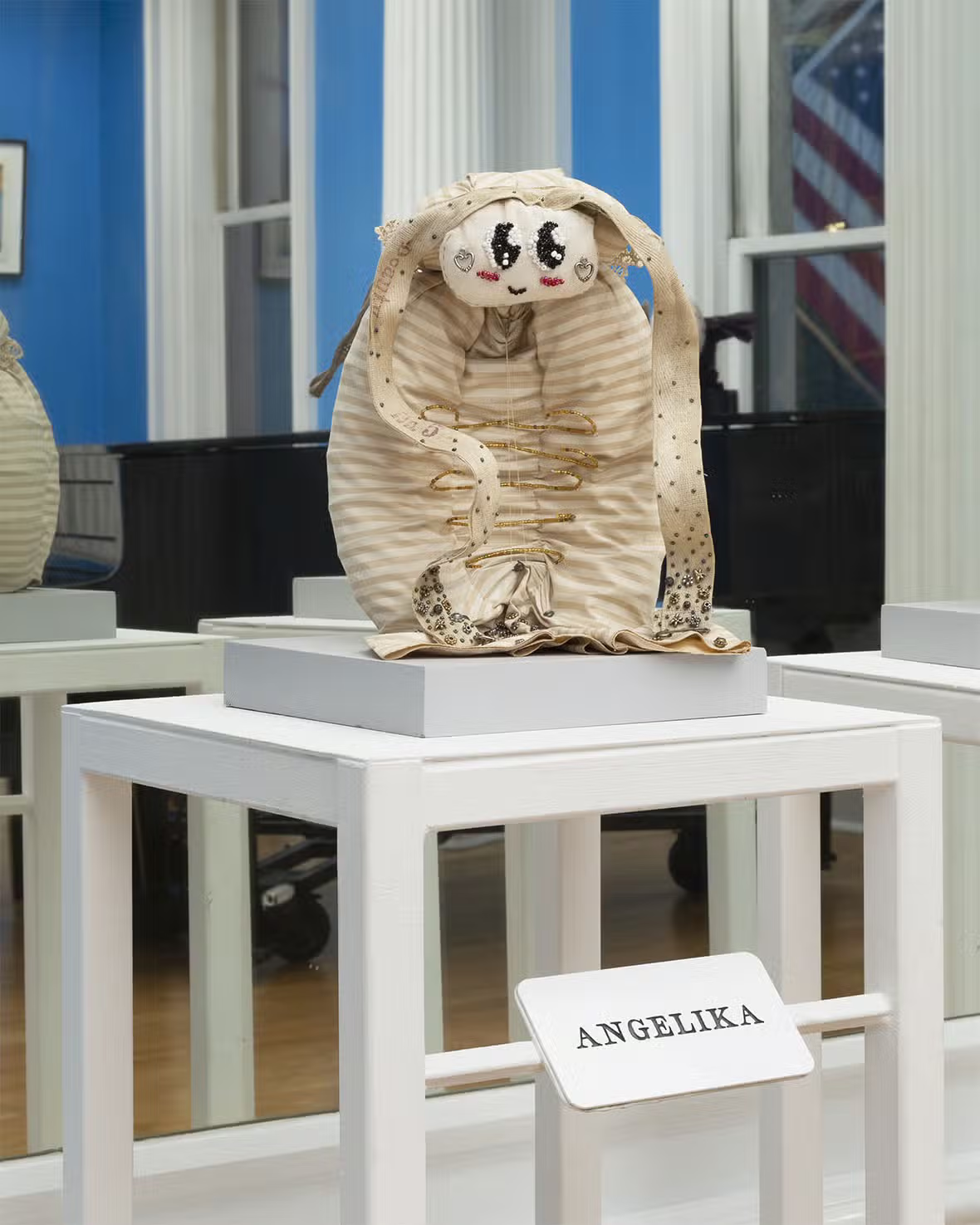

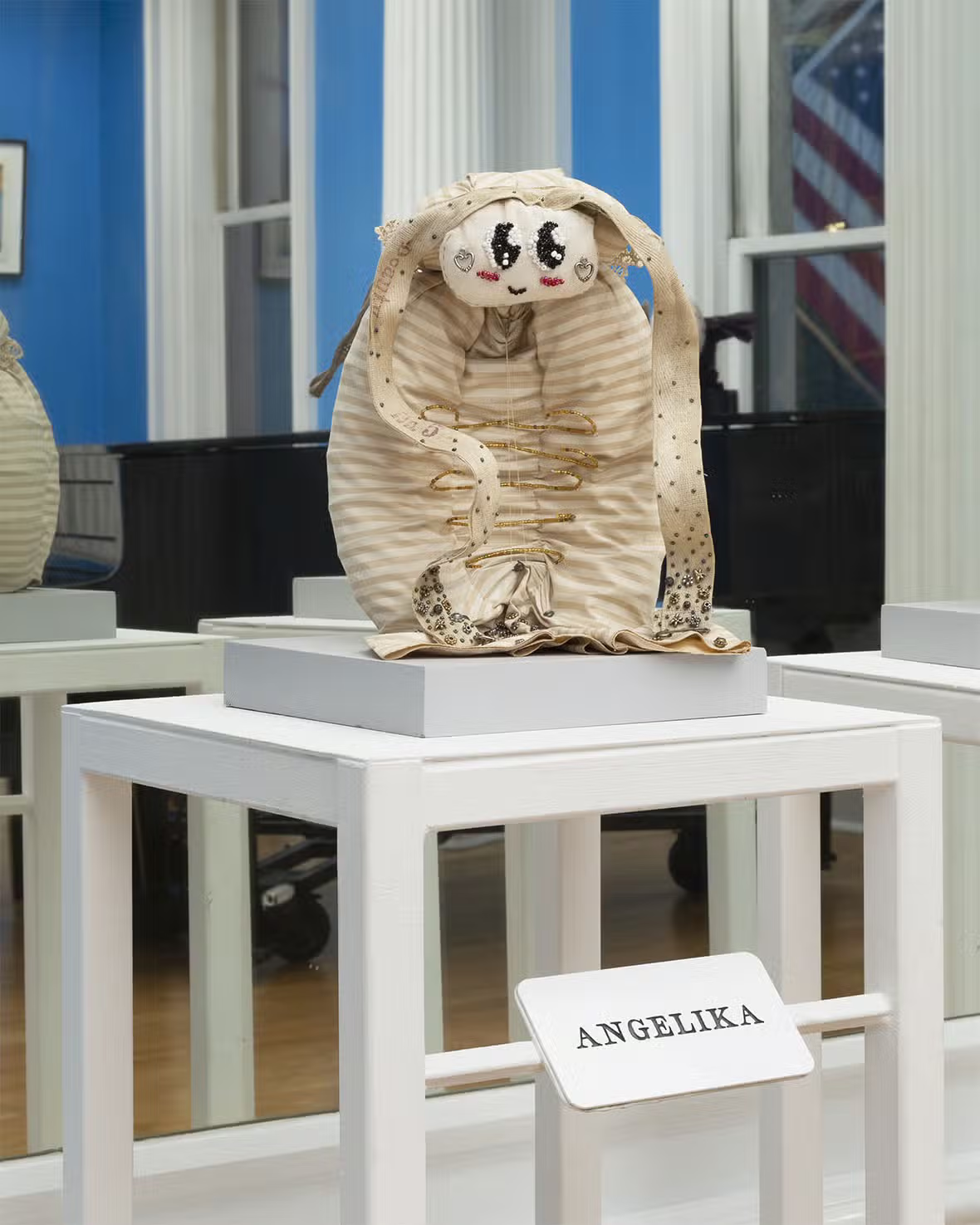

Martina Cox, Angelika, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Alyssa Davis Gallery.

In her show, “Waist Management,” Cox takes a proverbial scalpel (and her own very real needle) to 19th century bodices and bustles. Hosted at the New York Estonian House with Alyssa Davis Gallery, Cox proffers a series of sewn sculptures and drawn, hyperreal depictions of these garments’ splayed-open insides—or “guts,” industry slang in costume design, as Cox explains to me. With these pieces, she’s also pierced through the paper and sewn it with thread, a subtle pronouncement of the bodices’ own original stitchwork.

Her reference images are plucked from the bidding site listings Cox regularly lurks (antiquedress.com is a favorite for the artist, whose 2D-interface looks like it hasn’t been updated since the turn of the century). “They’re so haphazardly taken, thrown open purely to document the quality of the inside,” Cox says. “But while I was spending time on these sites, I started to fall in love with the photos of the listings, especially the insides. They looked so beautifully abstract.” These photos are of the documentarian strain, digital retail conventions which, close-up and removed from their original context, render the bodice viscera as something more akin to an alien planet landscape.

Martina Cox, Gut Flora a gaping mouth, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Alyssa Davis Gallery.

Lushly pigmented with rich gem tones and elegant pastels, the “Gut Flora” drawings are almost psychedelically real. Their satiny folds and corset boning surge with a grotesque and beguiling life force: a sentient, teeming microbiome, their secrets spliced open for even the most insouciant outsider. Gut Flora a gaping mouth, 2024, for example, could be construed as the maw of some blue-tinged sea creature, lolling open for a dental inspection. Its “teeth”— where Cox has punctured and sutured the work—are also a spectral performance of invisible feminine labor. Known as whipstitching, garments from this era had to be fastidiously sewn together, seam by tiny seam. “I was originally really drawn to this labor of love, to whipstitch the inside of every single inseam, because it’s such a painstaking process. And most people then only had two or three outfits to wear, so everything was very intentionally created to last throughout their life,” she says. “It’s an intense care and emphasis on craft that creates this durability. I wanted to honor that work.”

Looking at the meticulous tenor of Cox’s practice, it makes sense that rigor and precision, in other, non-art forms, were constituent to her adolescence. Born and raised in New York, Cox trained intensely as a gymnast from a young age and attended Bronx High School of Science. Equally fundamental was her curiosity for the alternative and underground. It was also during this time that she became enmeshed in the rave scene in the city, which later informed her post-college stint in Berlin. (“I basically lived at Berghain for a summer,” she laughs.) In that in-between period, she pivoted to art school to study at The Cooper Union, primarily focusing on painting and photography. Her senior thesis show, another pivot, unwittingly launched her into a years-long art practice centered on clothing design, as well as a full-fledged fashion line. The works from that show—girlish, innocuous pieces inlaid with miniature cut-out windowpanes of clear PVC vinyl, cheekily placed on the garments’ chest or as a replacement for back pockets—struck a resonant chord and were quickly sought out by the downtown fashion scene, where her garments regularly sold out at the beloved concept store Cafe Forgot.

Installation view of "Martina Cox: Waist Management." Image courtesy of the artist and Alyssa Davis Gallery.

With her eponymous fashion brand, Cox carried this through-line for as long as financially and creatively tenable, though she felt the urge to develop her practice in other ways. “There was no way to expand; there was no business model that worked for me,” she explains. “Being so financially dependent on my work was actually so taxing on my creativity.” This led Cox to close the line and return to New York. Instead she pursued teaching art for elementary students as well as other side gigs, which became a moment for incubation and reflection. “I was interacting with kids in a creative way and not having the pressure to maintain the line. And it helped me realize that my clothing-making had been a studio practice the whole time: It was performative, and it was sculptural. I just hadn’t framed it like that in my head.”

The love and creative vigor Cox felt detached from for so long is clearly manifest, alive and kicking, in “Waist Management.” Alongside the drawings which took two years to complete, Cox has also created a series of soft sculptures, perched atop the grand piano in the azure-blue drawing room of the Estonian House. Hewn from 19th-century bustles and reconfigured as plush characters, they have been embroidered with beaded eyelashes, sparkling anime eyes, and gentle, demure smiles. I’m particularly fond of the “Horse Girl” series, three works stuffed with horsehair that resemble varied phases of the moon, and also a bit like handbags. Gallerist Alyssa Davis described them, spiritually, as a kind of “vegan taxidermy,” reliquaries containing the lives of their former wearers from centuries past. The girls are nestled in beds of hand-smocked, dyed, and starched fabric, another demanding design craft of yore that Cox has implemented in the present. “Waist Management,” then, is Cox’s gift of attention: calling forth the secretive and hidden: what has been warped by the passage of time, changes of industry, shifting social mores. And here, the artist is the vessel, the seer and arbiter.

“Martina Cox: Waist Management” is on view by appointment through December 19, 2024 with Alyssa Davis Gallery at the Estonian House at 243 E 34th St, New York, NY 10016.

.avif)