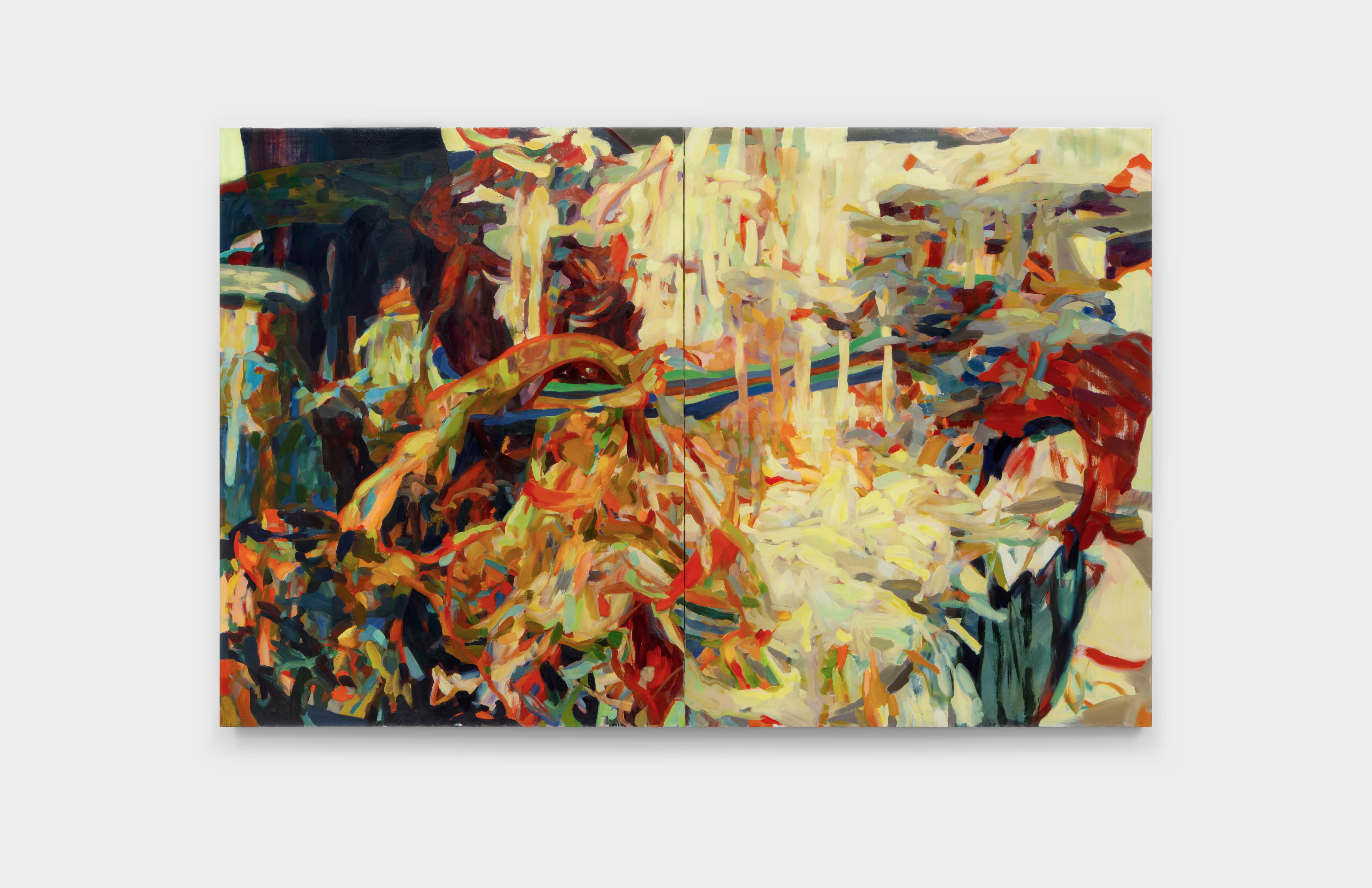

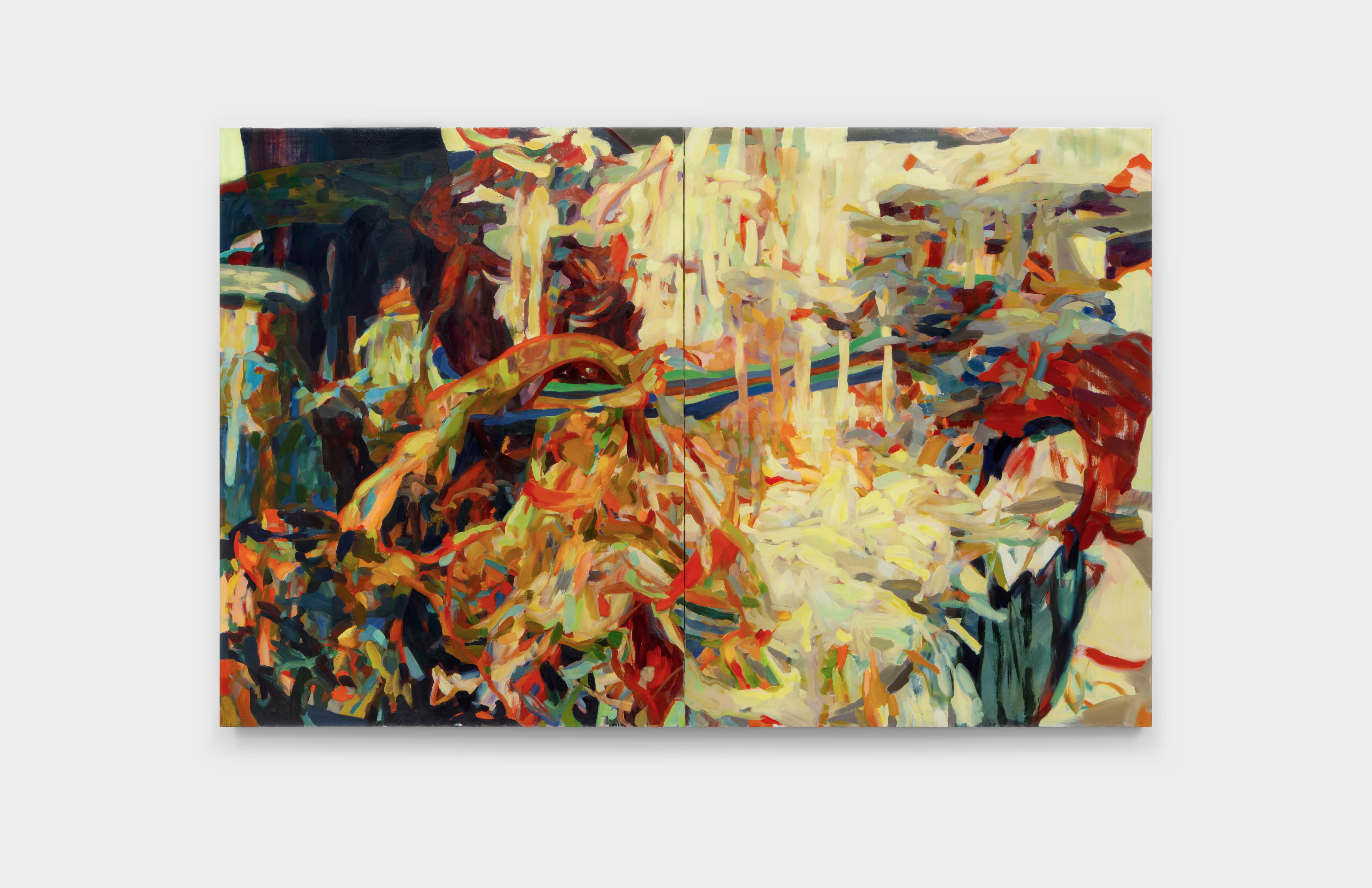

Nina Kintsurashvili, Misdated Object, 2025. Photography by Grigoriy Sokolinsky. Image courtesy the artist and Polina Berlin Gallery, New York.

Nina Kintsurashvili received her art education across remote destinations within Georgia, accompanying her father, Lasha Kintsurashvili, a renowned fresco painter and calligrapher, as he restored decaying works across the country. It was during these travels that the artist developed her own visual language, influenced by Mkhedruli (the curved script of the three Georgian alphabets), religious imagery and iconography, medieval murals, arahceolgy, and frescoes found in cathedrals and monasteries. “Now I try to portray the essence of those ancient environments,” says Kintsurashvili, who was born in the capital of Tbilisi just a year after the nation declared independence from the U.S.S.R. She recalls observing light travel inside the narrow church windows and the way frescoes traced the arches.

“Before painting I always ask myself, What kind of space do I want to create?" she tells me from her studio. Somewhere in between abstraction and figuration, gently rounded gestural strokes intertwine with vigorous motions, forming a lyrical composition that she painstakingly reduces and adds to, layer after layer.

Nina Kintsurashvili, Verse I, 2024. Photography by Grigoriy Sokolinsky. Image courtesy of the artist and Polina Berlin Gallery, New York.

At Polina Berlin Gallery in Manhattan, Kintsurashvili presents six new works created over the last two years. Imbued with references from her past, their colors are guided by her intuition. Aptly titled “I Met a Traveller,” Kintsurashvili’s current exhibition is her first solo show in New York. On view through the end of the month, it gives viewers a glimpse into the complexity of her own Georgian history, identity, and memory.

Still based in Tbilisi—a democracy slowly transforming into an oligarchy in the midst of the political turmoil—Kintsurashvili got to work. The artist had to make a tough decision, with the current unrest stemming from mass protests triggered by the Georgian parliament’s advancement of a controversial “foreign agents” bill closely resembling Russian-style authoritarian legislation. “Being an artist anywhere today is extremely hard, but in Tbilisi it comes with even more responsibilities,” she says. “Almost every day you ask yourself: Do I go to a protest today to be beaten up, or do I go to the studio to paint?”

Nina Kintsurashvili, Mute Things, 2023. Photography by Steven Probert. Image courtesy of the artist and Polina Berlin Gallery, New York.

While most of her paintings are on square canvases, Mute Things, 2023, consists of three angled panels standing independently on the floor, like a large room divider. “I wanted to make a painting impossible to see as a whole from one angle,” she says of the work. Its 45-degree corner breaks up the surface in a reference to architecture. “If you stand too close it will wrap around you like a fresco.”

The compositions on view may seem abstract, but they are deeply referential. “You can never escape the visual culture you grow up with,” Kintsurashvili shares. “Some references are conscious, through research and studying of images and places, but most come out subconsciously and only make sense after I’m done working.”

.avif)

Nina Kintsurashvili, Death by the landscape, 2024-25. Photography by Grigoriy Sokolinsky. Image courtesy of the artist and Polina Berlin Gallery, New York.

As the artist works through her memories and her relationship with her heritage, she is also preparing for what might be her most intimate project yet. This week at Konsthall C in Stockholm, Kintsurashvili opens the exhibition “Udabno” with her father, marking the first time her work will be shown alongside his small, figurative paintings made during the civil war. “I always see intergenerational differences between me and my father in the wider historical context of Georgia. His generation was that of dissent, activism and self-sacrifice,” she explains. Whereas the 32-year-old artist characterizes her upbringing in the newly independent country as a different beast. Up until adulthood, she only saw Western art in poorly printed Soviet-era books, but she was exposed by an onslaught of wide-ranging visual information produced by “chaotic capitalism.” “When I think about a partially erased or vandalized mural or a broken artifact, I don’t feel the desire to see it restored into its initial form,” she muses. “I’m more interested in the trace of time. In some sense what we inherit in its most damaged form is already a completed work.”

“I Met a Traveller” is on view through April 26, 2025 at Polina Berlin Gallery at 121 W 27th St, Unit 704, New York, NY 10001.

.avif)

.avif)