.avif)

Sedrick Chisom, Medusa Did Not Spread Gangster Rap Lyrics to The Youth of The Southern Cross, but She Did Not Care to Contradict Her Accuser, 2024. Photography by JSP Art Photography. Image courtesy of the artist and Clearing New York/Los Angeles.

A new painting by Sedrick Chisom, titled Medusa Did Not Spread Gangster Rap Lyrics to The Youth of The Southern Cross, but She Did Not Care to Contradict Her Accuser, 2024, places the mythic Gorgon in a setting both antebellum and post-apocalyptic. Medusa’s hair flies into a yellow sky while her feet melt into the earth. Intense, vertical drips define her silhouette against the bright landscape. The viewer looks at Medusa through a dark frame that enhances the image’s storybook quality and troubles notions of danger and viewership: Medusa, famously, can turn onlookers to stone. Yet back turned, she looks out to the horizon. In Chisom’s imagining, she is only “guilty of sharing carnal knowledge with the light of the morning star, guilty of listening to the forest whispers of Shub Niggurath."

The painting is featured in “...And 108 Prayers of Evil,” Chisom’s debut solo show in New York, on view at Clearing through June 8. It marks the New York-based artist’s third presentation with the gallery’s director John Utterson and includes a textual preamble, printed across a wall, that grounds the new work. In the not-so-distant future, the presidents of “Altrightland'' have found Medusa “guilty of crimes that are worthy of death.” Instead of contending with their “hateful hearts,” a “revitiligo” epidemic that has turned their skin black, and an impending magmatic eruption, Altrightland’s citizens pursue Medusa, the “demoness” and “outside agitator.” Yet Medusa appears unbothered. “She has peace of mind,” the artist says. “She’s outside the social community, but her goal is to achieve a community of her own.”

Portrait of Sedrick Chisom. Photography by Nancy Kote. Image courtesy of the artist and Clearing New York/Los Angeles.

Chisom has a similar worldbuilding instinct. The artist wrote a three-act play, titled 2200, 2018, during his time in the Rutgers MFA program. He graduated in 2018 and has subsequently used the text-like sheet music to inspire drawings, paintings, and exhibitions at-large. Chisom notes the long history of artists who also worked in set and stage design—fields similarly invested in space, drama, and light. With each new exhibition, he expands his own creative universe.

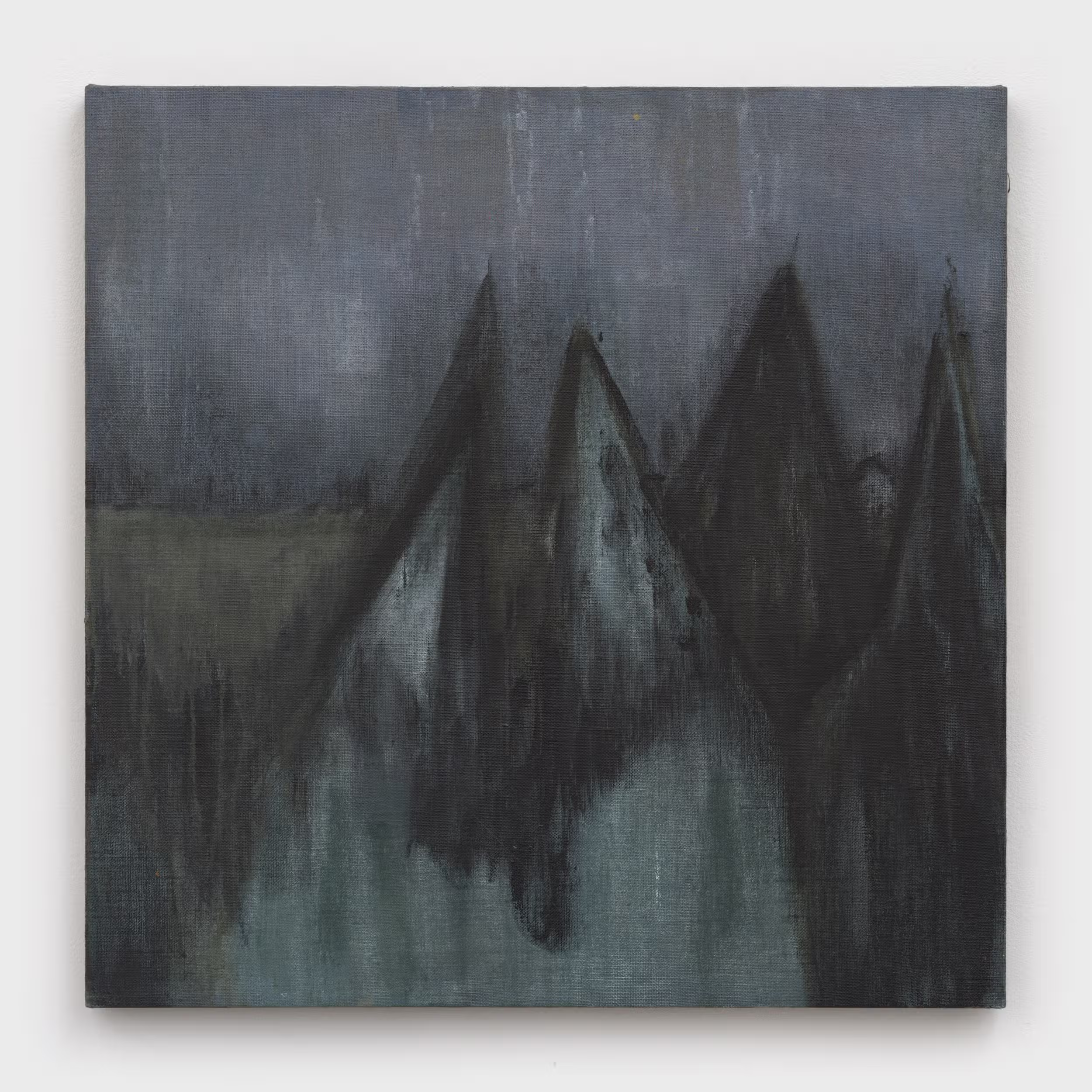

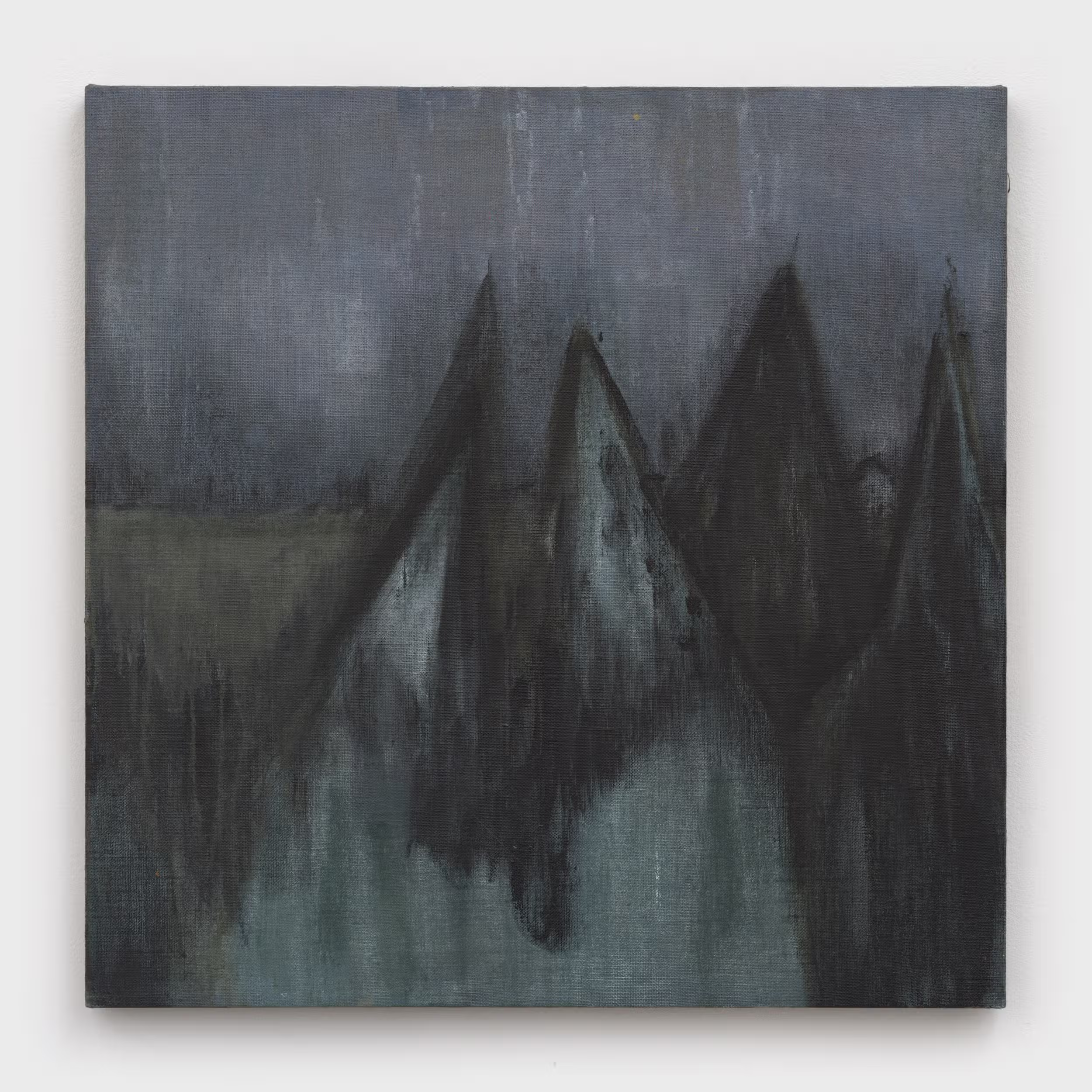

At Clearing, the artist unites Medusa with a bevy of characters. The General of the Northern Armies stands against a blood-red sky, while heads and limbs appear on stakes before the Capitol building. Foreboding shapes resemble jagged mountains or hooded members of the Klu Klux Klan in Prayer of Evil, 2024. Elsewhere, two cows graze amid a green and purple landscape. The lonesome figures, Chisom says, “exist in intensified, anxious spaces” and project their fears onto Medusa, the “other.” The show’s title derives from the Buddhist teaching that evil is misfortune, that ignorance confines humans to patterns of destruction.

Sedrick Chisom, Prayer of Evil, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Clearing New York/Los Angeles.

Such tensions between tranquility and doom, natural beauty and human misdeeds, find their corollary in Chisom’s formal decisions. The artist begins by layering acrylic onto unprimed, unstretched canvas. Once he finds a sense of light and space, some kind of “primordial mist or cloud or swamp,” as he says, he seals the canvas, then builds subsequent layers and sands them down. Paint simultaneously sits inside and atop his surfaces. Drips suggest a literal sense of gravity, while vibrational color palettes enhance tension. “There’s a vulnerability and solidity about the material process,” the artist explains. “Half the large paintings have a granular quality. They seem iridescent. They’re thin and thick, vibrant and muddy.”

For the first time, Chisom integrates vitrines into his presentation strategy. They display source material including an excerpt from 2200 and Jean Raspail’s dystopian, xenophobic 1973 novel The Camp of the Saints, which has become a favored text for white supremacists. There is also an Alan Moore Swamp Thing comic book, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, and books on both “monstrous races” and women in the Civil War. Altogether the artifacts offer a record of the artist’s research, provide a damning account of racial prejudice in the Western world, and evoke an off-kilter natural history display. Chisom imagines who might be collecting this material and narrating the textual preamble: “The voice comes from one of those alien guys on the History Channel. A disheveled academic with little credibility.”

Chisom maintains a sense of humor and play despite his ruinous vision of the future as well as his reckoning with the past. His description of Medusa reveals a larger attitude towards his work: She’s not a stand-in for the artist, he notes, but a mystic. And the histories of art and mysticism are elitist, granting secret knowledge to the few. “I’m not trying to have moral authority, to occupy this position of wisdom, casting judgment on everything,” he offers. “I’m commenting on traffic while inside traffic. I’m also the traffic.”

“Sedrick Chisom: …And 108 Prayers of Evil” is on view until June 8, 2024 at Clearing at 260 Bowery, New York, NY, 10012.

.avif)

.avif)