Wilhelm Sasnal’s paintings are stacked neatly in the corner of his northeastern Los Angeles studio. It is the day before the work leaves for his New York solo show at Anton Kern Gallery, and the outsized, industrial space is only partially occupied—a result of the artist’s temporary station there. As a periodic Californian, Sasnal taps in and out of SoCal’s frequencies with the detachment of an outsider blended with the discernment of a temporary denizen.

Sasnal welcomes me at the door before pivoting in and away from the Angelinian sunlight. He wears a yellow Stereolab T-shirt and glides across the room as we speak about the connective tissues between music, graphic design, and painting. Born in Tarnów, Poland, Sasnal moved to Krakow in 1992 to study architecture before switching over to painting. Since then, he’s remained faithful to the medium while also producing multigenre films.

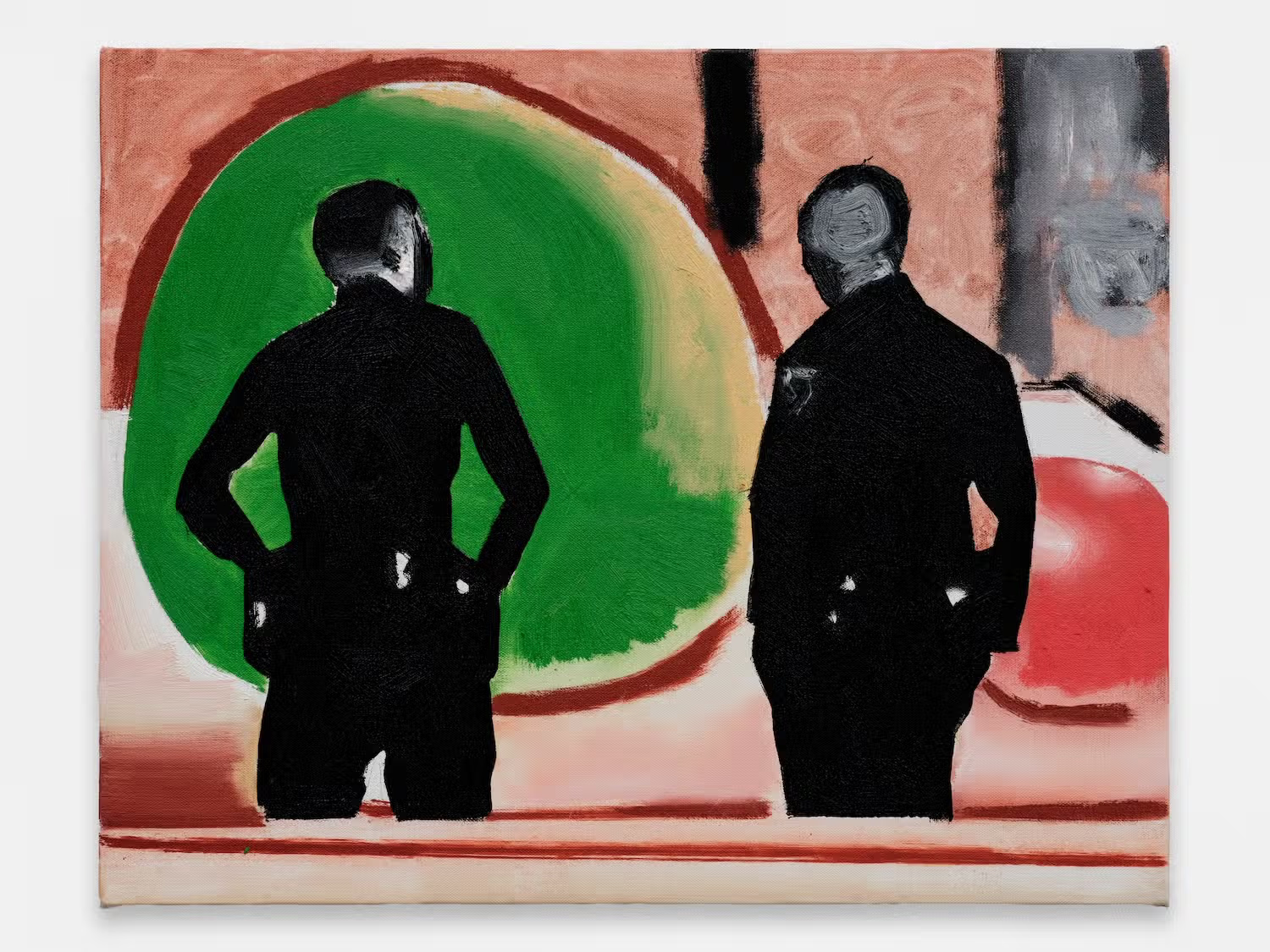

There is no value system attached to Sasnal’s choice subjects, but rather an acceptance of the image’s fluidity. The artist pares down visual matter, drawing from his interest in iconographic materials like album covers and film posters, arriving at compositions that register with ease. As such, Sasnal is often parsimonious with details. His new works at Anton Kern Gallery, all made in 2024, lean on the basic structure of the given subject. With Untitled (Two Policemen in Front of Fruit Still Life), the officers are present in silhouette only, superimposed on an inscrutable pair of polychromatic fruit that become oversized in this new context. Another painting implicates the same botanical subject, albeit in this case the Cézannian orbs have been transported into a quotidian office space.

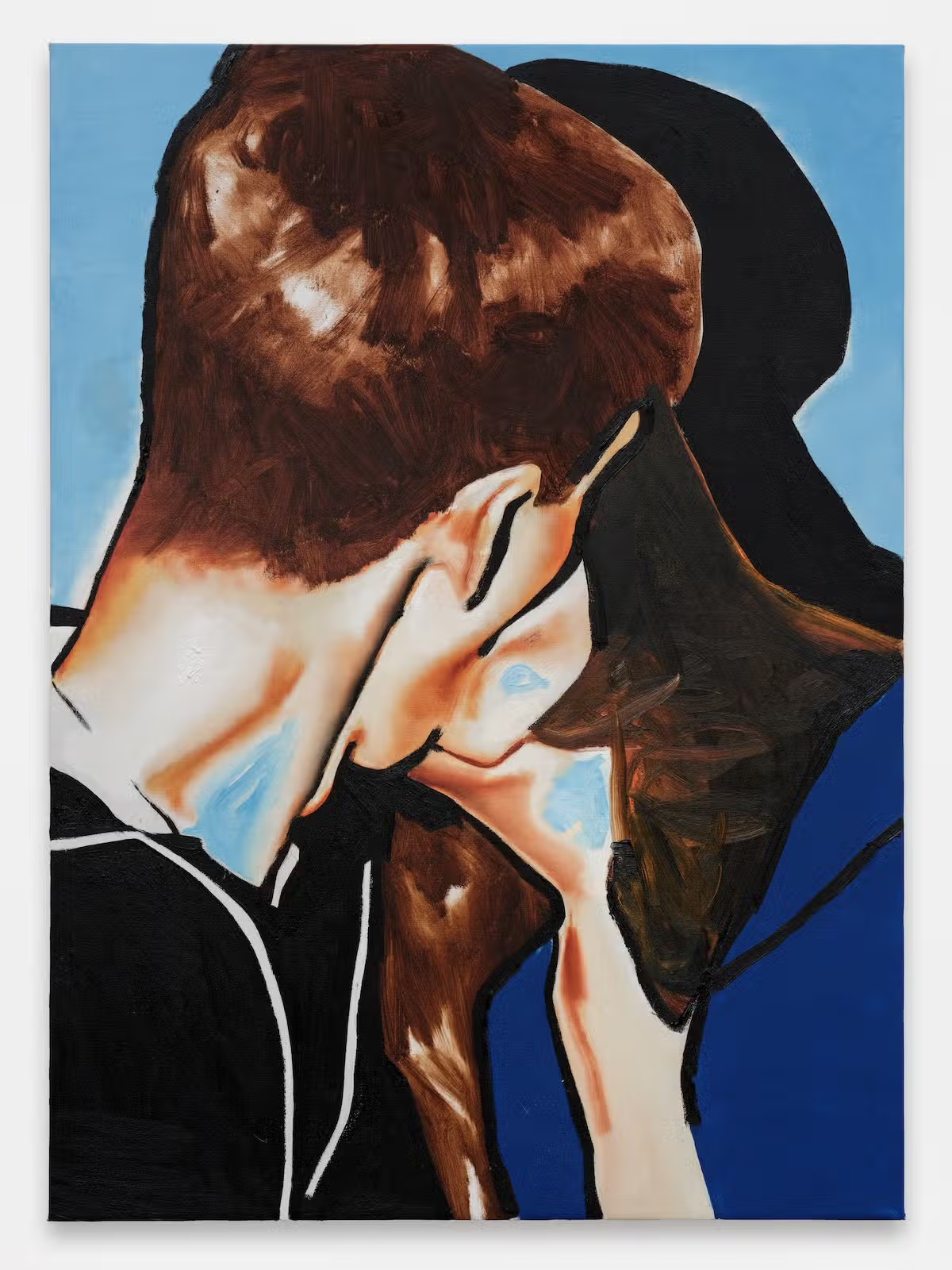

With Untitled (The Kiss), Sasnal opts for sky-blue highlights in yet another move away from photographic fidelity, which he describes as putting the painting into “overdrive.” As he ambles around in painterly territories, he refuses submission. “I’m not going to stick to the source materials unless it’s for the sake of painting,” he asserts. His formal strategies lend to an amorous moment: The site where the lovers’ lips touch is the only point where dividing lines are absent, and their faces dissolve into one another. Everyone who has ever been kissed knows exactly what this feels like, to completely disappear into a sensation. This is not Sasnal’s first depiction of the intimate exchange. “It’s always striking, it’s like peeping. It’s something private,” he contends.

Sasnal observes the city’s contours, from curbside trash cans to ominous graffiti on an Echo Park transformer box. His preferred vantage point—from the seat of a bicycle—becomes a director’s chair as he captures the sprawling urbanity in motion. In both Tristes Tropiques and Untitled (All American Asphalt), Sasnal directly refers to the road’s surface quality, using frottage to generate the rhythm of asphalt. Other paintings, like Berkeley Street and Untitled (Corona Truck), proffer the hum-drum aspects of life in this suburb-as-city. However, Sasnal’s subjective decision to paint explodes the potential of the mundane.

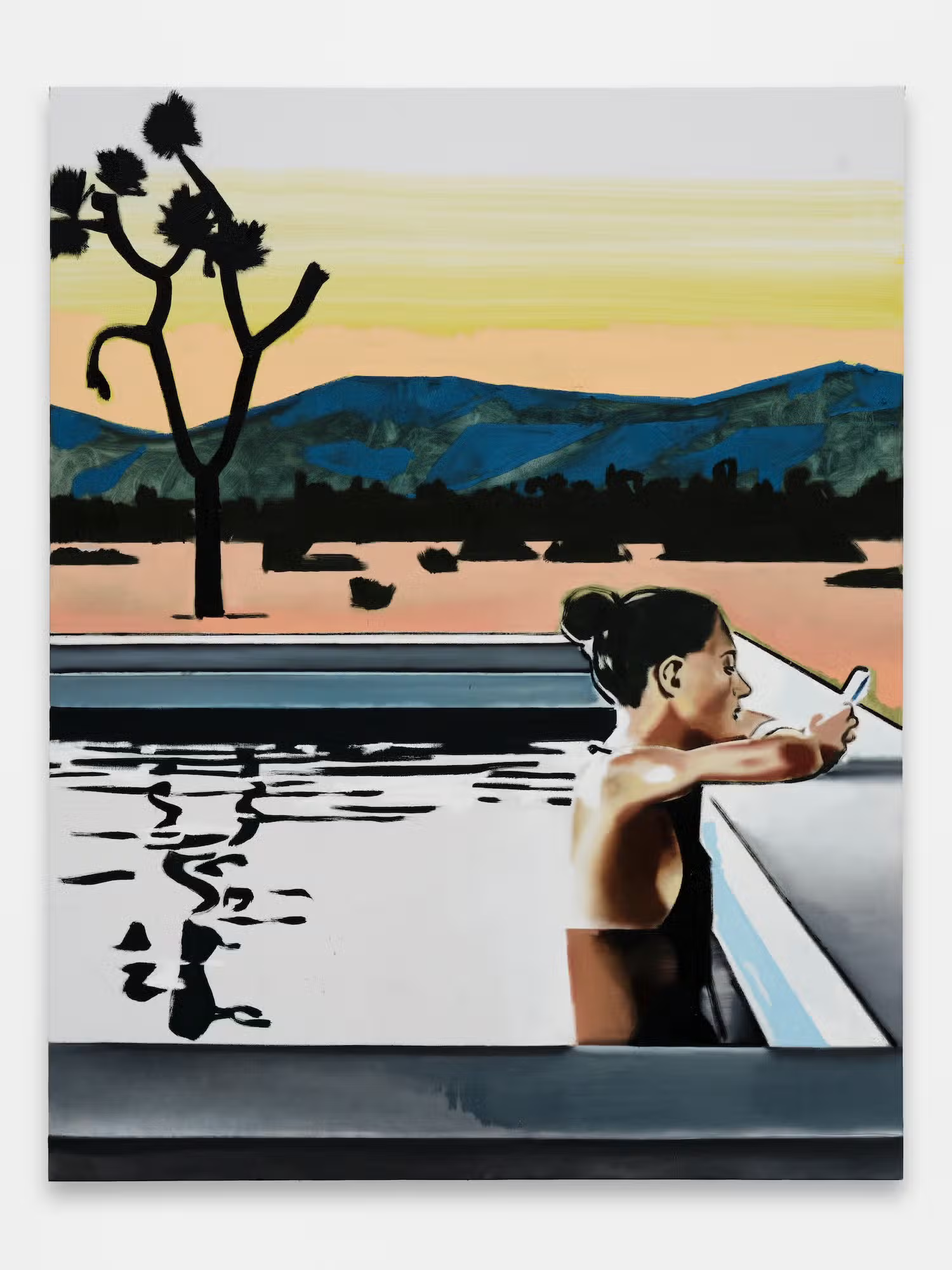

Abandoning the metropolis, in Untitled (Rita in Pool) Sasnal’s daughter takes a break from swimming to text at the pool’s edge. Behind the figure, Joshua Tree’s geography is inverted in the water and reduced to calligraphic abstractions. A companion picture, Untitled (Green Landscape with Electric Poles), sees the contours of power lines frame a sun setting on the outskirts of town. Moving further up the coast, dual images of Bodega Bay allude to Monet’s Normandy shorelines. The impressionist seascapes are traded in for high contrast ones, as Sasnal attaches a film noir texture to his family vacation.

There is no value system attached to Sasnal’s mode of work, but rather a visual fluidity. Ultimately, the world is material. Fragments from museum objects, doom scrolling, cinema, and variable ephemera meet the sentimental landscape of domestic life. Sasnal approaches selection with discernment, indexing choice visual matter, therefore re-enchanting detritus from a hyperimaginal culture. Most compositions in this exhibition refer to Sasnal's American context, however a few choice outliers alert the viewer to the confluence of experience and projection.

To this end, Sasnal applies a discrete, painterly language to found images. “For me, the painting itself is always an independent being,” he clarifies. By cataloging the torpidity of common photographs, the artist becomes a pictorial mechanic whose process greatly transcends the limits of the camera. “I’m not interested in pure execution,” he continues. “When something is too easy I am suspicious.” During the act, different aspects start to materialize and historical materials flutter in by chance. Sasnal mentions his subconscious references to Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko in Untitled (Wall with Cardboard Boxes), with his adherence to a reductive approach when describing a location.

All of these decisions that happen in solitude are exploded when it comes to staging an exhibition. The medium itself is extended beyond the studio’s confines and into the white cube, where paintings can weave and bind amongst each other on a brand-new stage. The day after install, we speak again—this time over the phone. I refer to his heterogenous practice as collage-like, becoming montages of the works on view. He agrees, “When I hang the show, it’s like film editing… These are the scenes, and I can somehow anticipate in the viewer a perception of the images, of the sequence, how one enters the room, how the paintings come one by one.” Sasnal thus obfuscates certain truths and narrative through lines: ”It’s better to suggest than to expose.”

“Wilhelm Sasnal: Sad Tropics” is on view until March 6, 2025 at Anton Kern Gallery at 16 East 55th Street New York, NY 10022.

_1.avif)