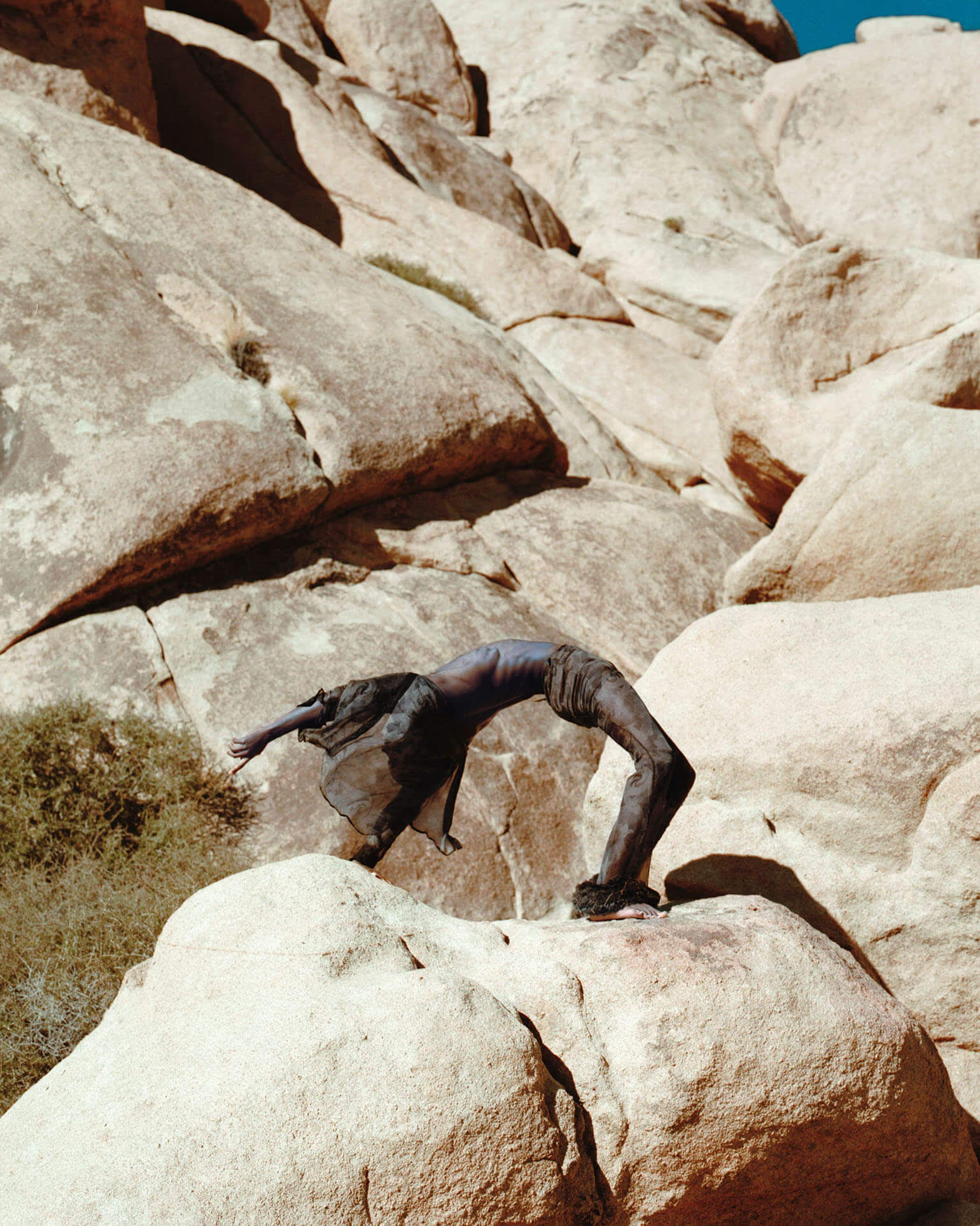

Alton Mason wears skirt and pants by BOTTEGA VENETA.

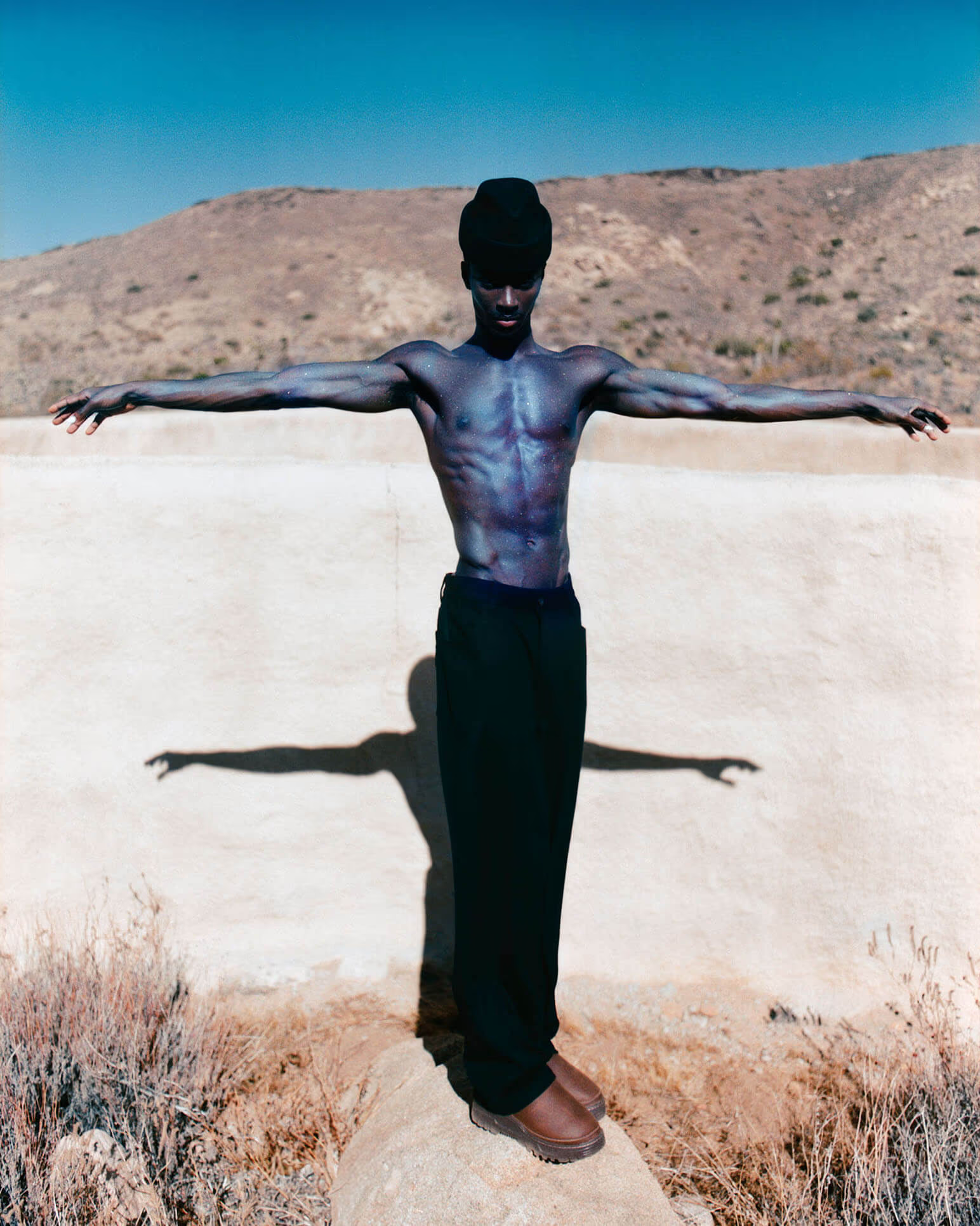

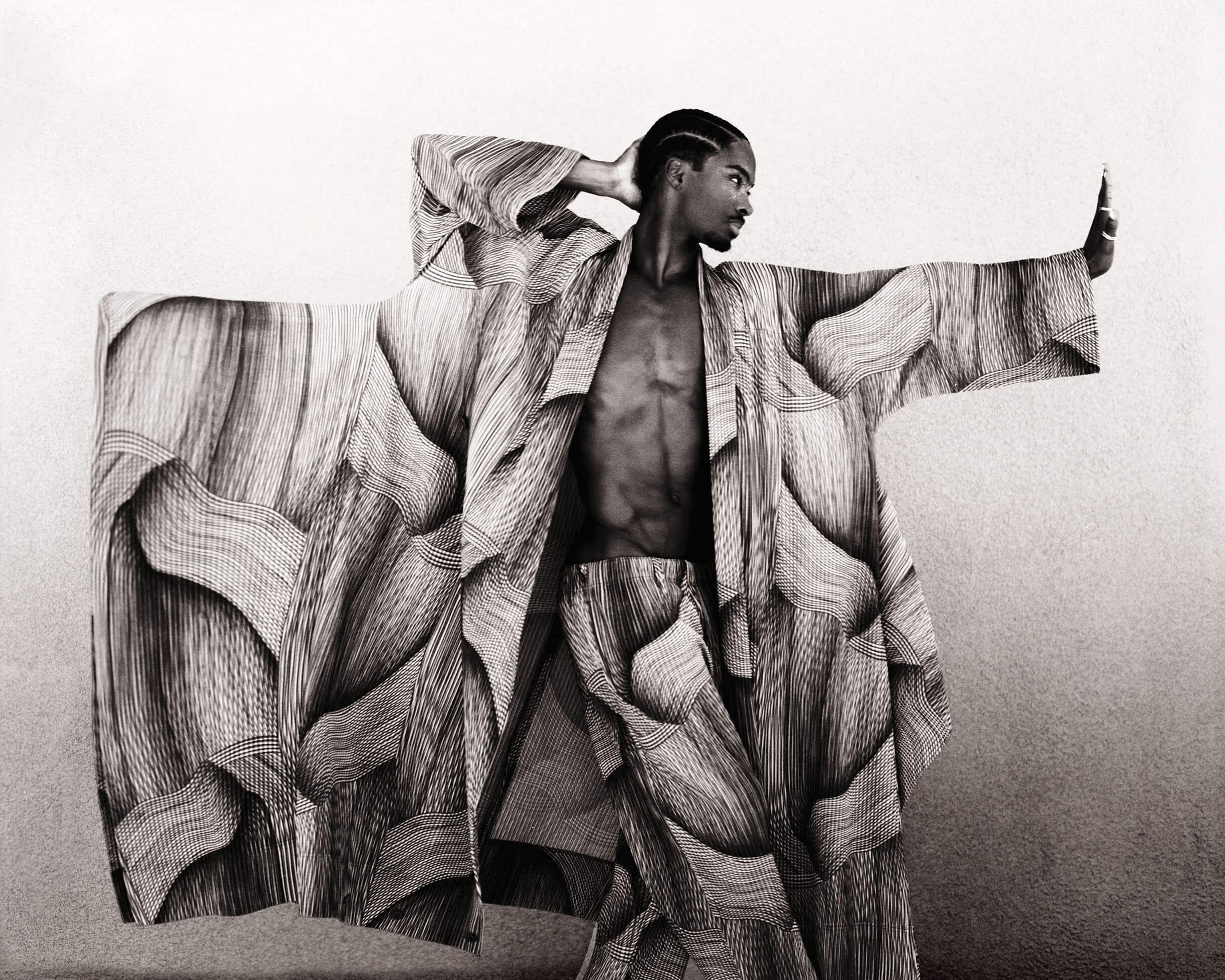

On the runway, Alton Mason glides with rhythm, allowing his spindly body to pulse with precision. His expressions exude swagger—a slight smirk, a dalliance with his eyes—or sometimes, he does what’s in his spirit, like when he did a backflip at the Louis Vuitton Fall/Winter 2019 show after the late Virgil Abloh asked him to improvise. On the page, his pliancy is also apparent: elongated backbends, nimble shoulders, seemingly always knowing what to do with his arms. Mason moves with an assured confidence that comes from intimately knowing your body’s capabilities, a tell of his dance foundations. Before the 27-year-old became Models.com’s four-time Male Model of the Year and walked in more than 100 fashion shows, he was a dancer. Mason studied at the American Musical and Dramatic Academy and then interned for famed choreographer Laurieann Gibson. It’s what has set him apart from the get-go and propelled him from model to supermodel, a rarity itself in his industry.

Unquestionably, movement is central to photographer Ming Smith’s work as well. Her black-and-white images have rhythm to them, too. She plays with light, using long exposure to evoke the emotion of moving bodies and capturing performers like Grace Jones, Tina Turner, and the Alvin Ailey dancers. Smith, 76, who worked as a model early on to support her photography practice, was inspired by choreographer Katherine Dunham and studied modern dance. It’s why her distinctive photos have a surety to them: In order to break the rules of the medium, one must have spatial awareness and an understanding of form.

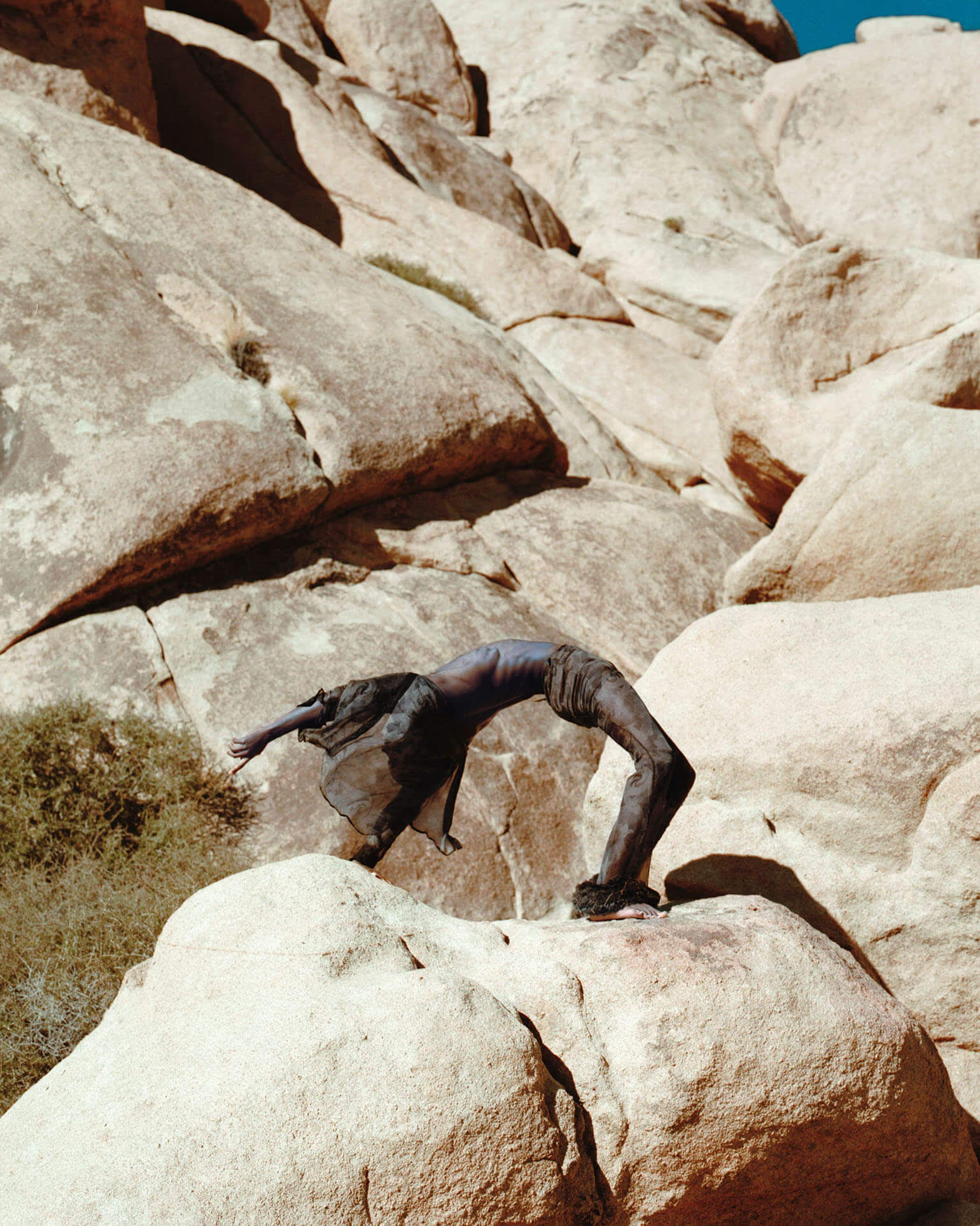

Alton Mason wears shirt and pants by ETRO.

Moving with confidence, and understanding our bodies, often translates to the way that we move in the world. In this way, Mason and Smith, decades apart in age, are connected in spirit. They both understood early on what it felt like to break boundaries—he became the first Black male model to walk for Chanel in 2018, while she was the first Black female photographer to be acquired by the Museum of Modern Art nearly 40 years earlier, in 1979. For the two iconoclasts, the best course of action has always been moving as themselves.

“Accomplishment is great, but once you make history, what do you do with it?”

— Alton Mason

Alton Mason: When I was coming into the industry, there weren’t many models who were dancers. The first male model that really started that was Sterling St. Jacques; he is a big inspiration for how I move and how I present myself today. Talking with you is a real honor because both he and you paved the way for guys like me, who started off dancing or performing and have used modeling to tell a story through movement. Moreso, you being a multi-hyphenate... I have so much respect for you to be able to literally move through this industry as a dancer, model, photographer.

Ming Smith: Just as you say I inspired you, you’re inspiring other people—other young artists, people who are trying to find their way. Art for me has always been a way of surviving, of trying to keep myself together, of not withdrawing. Some of us made it, but a lot of my peers at the time didn’t. I was fortunate to find photography—or photography found me—but so did dance. People look at us and say, “Oh they live a glamorous life,” but it was such a struggle, such a fight. Not just racial things, but within the family... not being accepted by my own mother and father. Like, “What the heck are you doing in New York?” Or, “You went to college.” And, “Oh, you dance?”

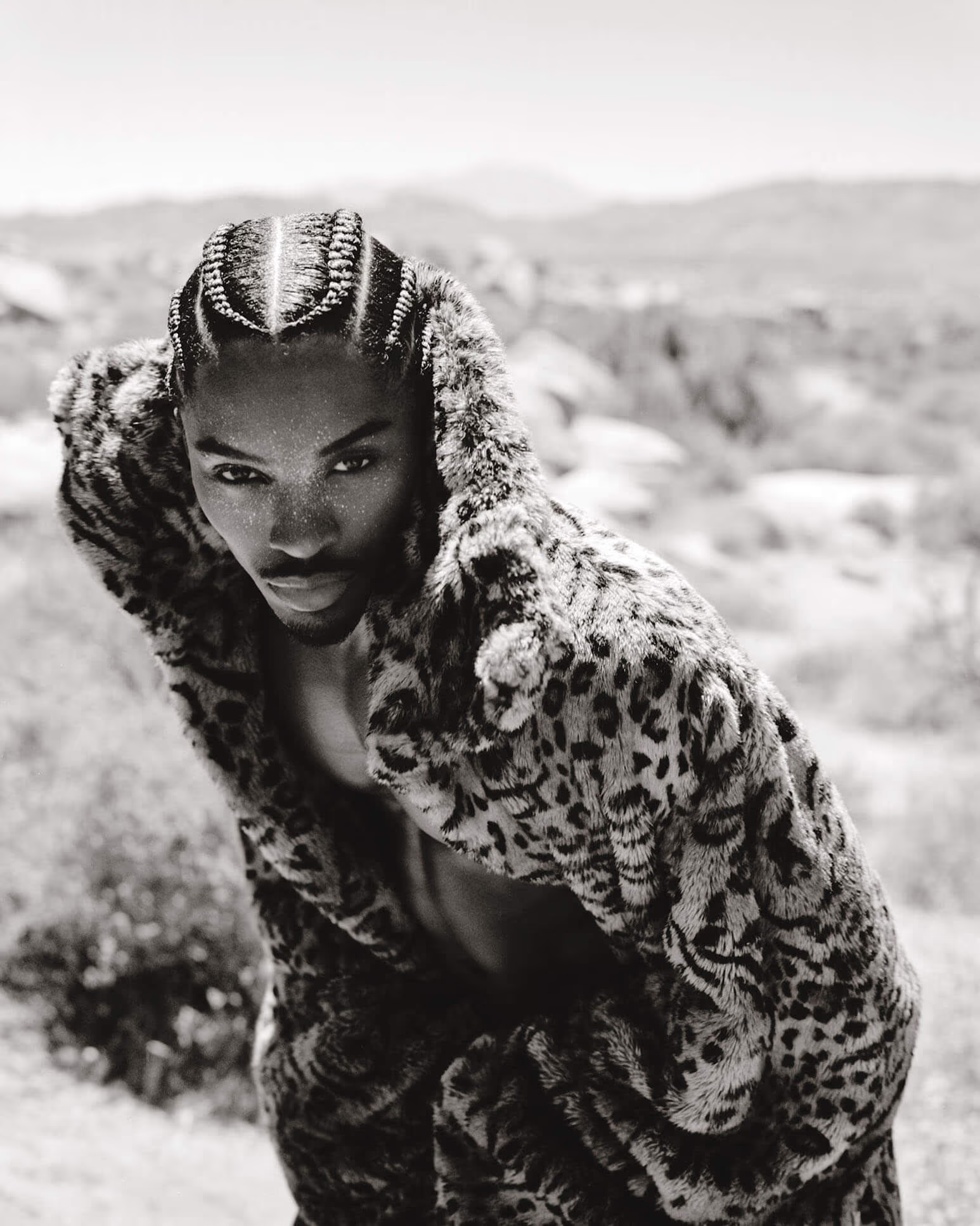

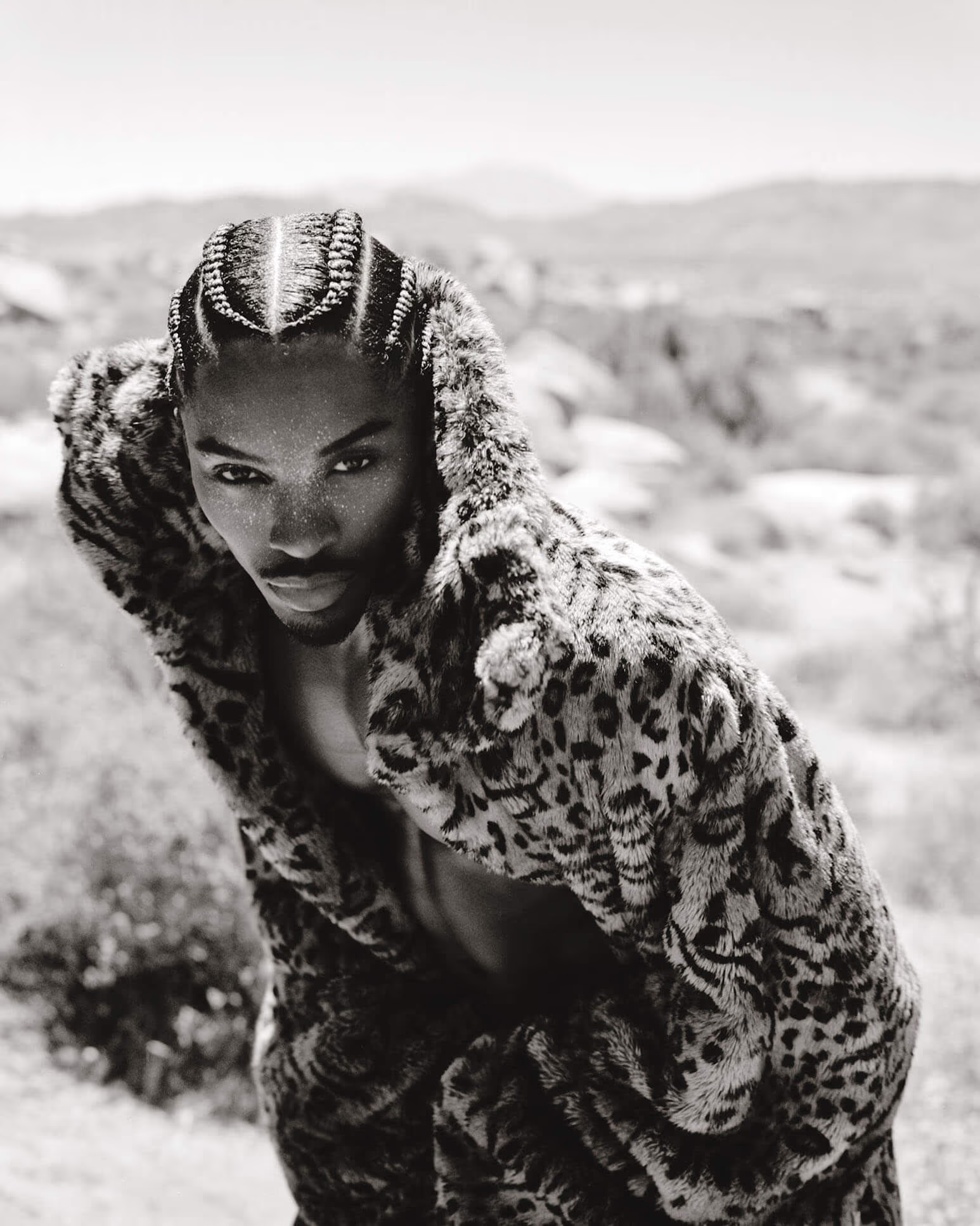

Alton wears coat by BALENCIAGA.

AM: I can only imagine the times you were in and how fearless you had to be to step into a studio or step into a room and just be. To live in your truth, and move the way that you know. I face a lot of adversity because they want us all to be hangers—to be stagnant and still. That constraint just doesn’t really work for me.

MS: We have to not worry about what other people are saying or doing. You just find the truth within yourself, and it’ll work out. You just do it, regardless of the times. I remember I took that photograph of Grace Jones in [the hair salon] Cinandre’s while Andre [Martheleur] was doing her hair in his iconic shape. We were girlfriends, and we talked about how hard it was—we just didn’t fit in. She was too much for people. I was, in my own way, quiet. Grace went to Paris because she wasn’t accepted here. They used to call us “exotic.” Now, people would take photographs of her. I remember going around—you would ask photographers to take photographs of you back then because you wanted to build your book and have different shots—but for most of us Black girls, they only wanted to use us to do nudes. And even afterwards, the business and advertising were cigarettes and liquor ads; that’s what they used us for. We all came to New York to be somebody: That was the main thing we had in common, and that we had each other as friends. Other artists had to support each other.

AM: Having a foundation of family and friends around you is truly what will keep you sane and keep you solid in an industry that wants you to change so much. I actually tried to play the game. I tried to go to castings wearing all-black skinny jeans, black T-shirts. You know, I tried to follow the formula. What ended up happening is that I’d call my mom at night and tell her, “Mom, I go there looking like the other guys, and I still get overlooked. No one’s seeing me, and I’m tired of this. I feel like I’m wasting my money. I’m wasting my time. I’m going to 20 castings a day, and all I’m getting is "Thank you, next." It was my mom who said, “Well, just be you. Go to the castings and show up how you would show up. Don’t listen to your agent. Just go how you would do it.” I listened to her. I started showing up to castings in this rasta tank top and a fur coat from the thrift store and leather pants and boots. I’d walk in, and the casting director would be like, “Wait a minute, who is that?”

MS: They were probably like, “That’s Miles Davis up there.”

AM: When you’re around a lot of dance, when you’re around a lot of performance, you’re around a lot of stars, and you’re around a lot of development, you’re gonna learn something. Working for Laurieann Gibson for like a year and a half... one of the biggest things she taught me is to be yourself. Find it. Be it. Whatever it is. Once I started making decisions based off of how I truly felt—as opposed to how I want people to view me or how I want their perspective of me to be—I started attracting what was meant for me, and that’s when things started working for me.

MS: Wow, that’s really beautiful.

Alton wears full look by JIL SANDER.

AM: A lot of us suffer from wanting to be accepted or validated in this industry. As we all grow up, we go through those growing pains. I’m blessed enough to have learned that earlier, and sometimes have learned it the hard way. You know when you leave a room and you just have that feeling like, Mmmm, something doesn’t feel right?

MS: I still have it everyday.

AM: You’re like, There’s something I wanted to say, or This is how I want to feel. This is who I am. I thank New York for that, too, because when I moved here at 18 by myself, I was forced to find it.

MS: At least you found it, because other people die trying to. At least you found it. That’s why you’re a success. That’s why you’re admired now. It’s our responsibility to help other people find it, you know? That was my purpose from the very beginning. From the very beginning it was about the culture. People like Romare Bearden or Elizabeth Catlett or Alvin Ailey. People have fought for you to get where you are now. People fought to get into these galleries. Faith Ringgold fought, protested. And it’s still going on. We’re still just in the beginning. We still have to fight for it.

AM: And that’s why I said in the beginning, thank you.

MS: I thank you, too, for reminding me, because I still go through it. Trust me.

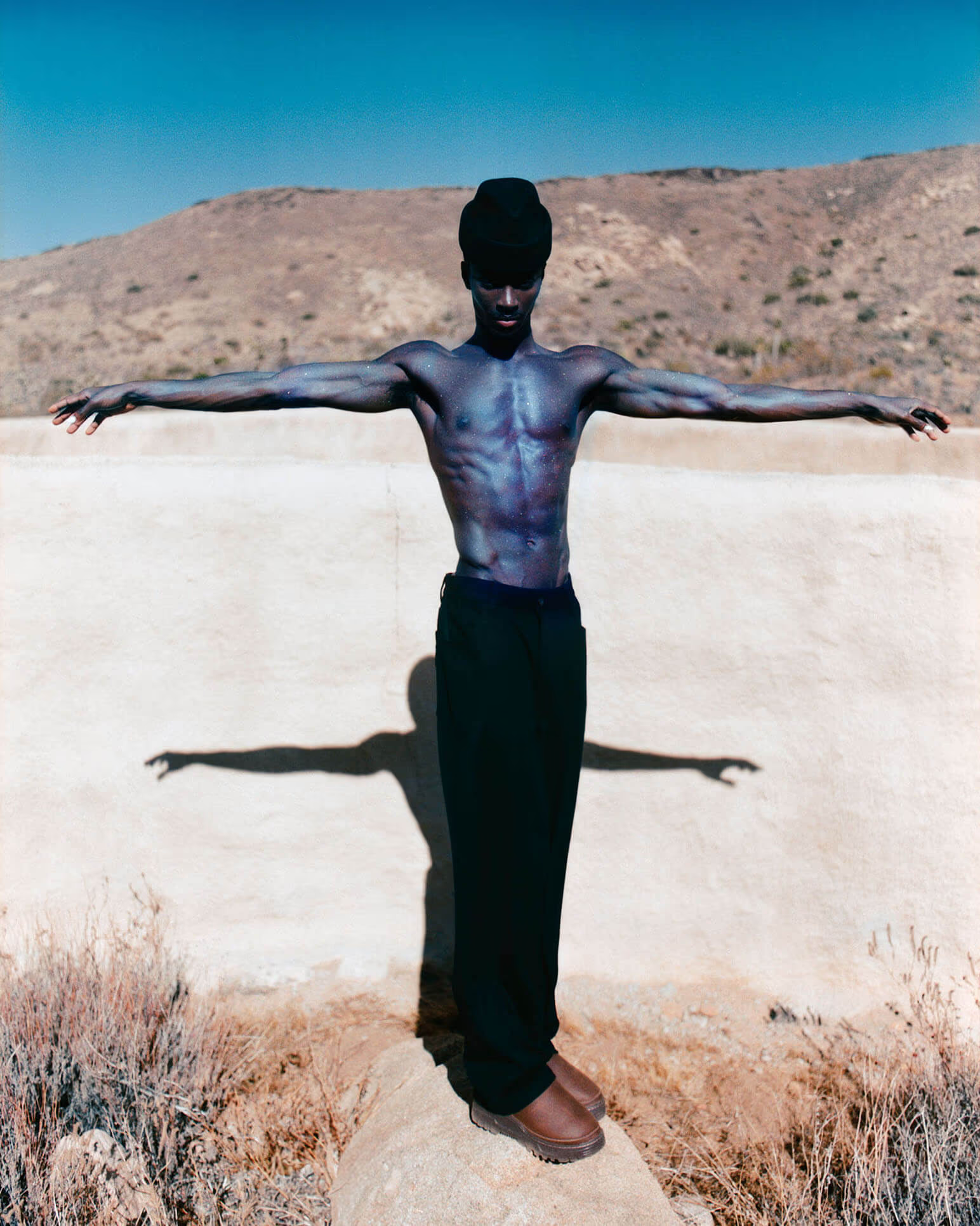

Alton wears pants and hat by EMPORIO ARMANI and shoes by UGG.

AM: Wow, that is crazy that you still go through it. I also admire you not only as a model, not only as a dancer, but through your photography: the people that you’ve chosen to capture and how you capture them and the stories that you’re telling. There is a lot of truth that radiates off of these photos. You’re seeing these authentic moments, intimate moments, with Grace, with Tina. As a viewer, I feel like I’m there.

MS: Also look at Talley Beatty, who was one of the main dancers with Katherine Dunham. He did beautiful choreography for Alvin Ailey. Dunham said—and I heard her say this at The Joyce [Theater]—that there were two young men, they must have been like 13 or 12, and they were trying to break into her studio in East Saint Louis, and she caught them. She was like, “Oh, you guys both have strong legs,” so she made them dancers, and look, they’re great. They traveled the world dancing. It’s beautiful. With the right energy and some direction and inspiration, anybody could become what they really want to be.

Alton wears vest and pants by BALMAIN and boots by LOEWE.

AM: When I became the first Black male model to walk for Chanel, it was celebrated. It was a very big milestone, and it made history in fashion, but I received a lot of adversity from it. It used to confuse me because I’m like, Dang. Why did it take this long? I know that it’s a women’s brand and that it’s an honor for a male model to walk in the show. It only happens once in a blue moon. Then, I did start to question: Why did it take this long, and is this something I should celebrate? I had to have a conversation with God, and God told me, “If not now, then when? And if not you, then who?”

I thank God for using me as an example and using me as his vessel for other up-and-coming models, and I thank the models that came before me who’ve made history and opened the doors for me, because now I’m opening the doors for others. I am starting the conversation with other brands and other casting directors and stylists and photographers who are seeing this news and seeing this history being made. Hopefully they want to make a change with whatever client or brand they’re working for. Like you said, you’re still facing adversity, and I wouldn’t want anyone who has opened the door or made change or made history to live in fear and start questioning the reason and the timing of it, because we still have a lot of work to do. Accomplishment is great, but once you make history, what do you do with it?

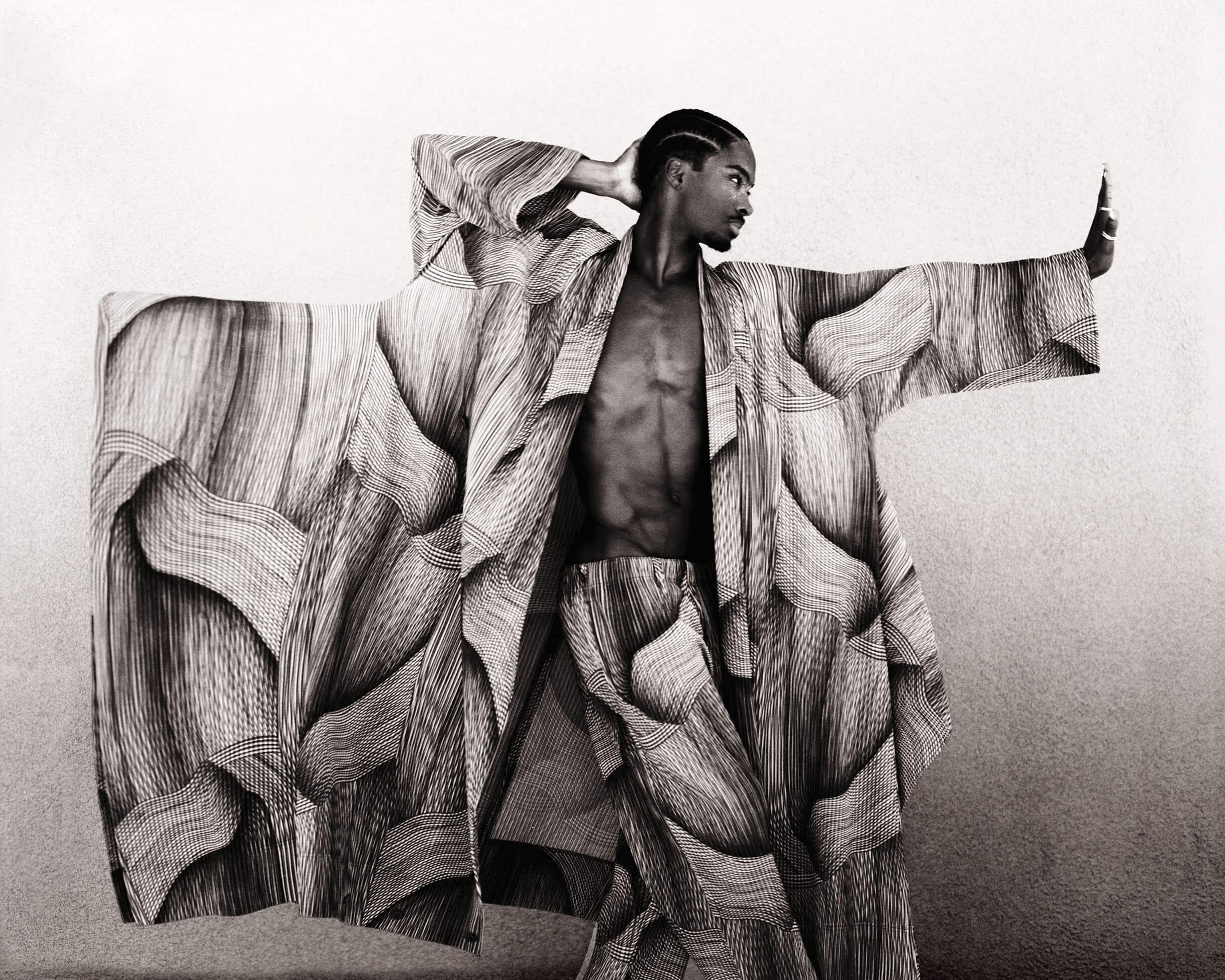

Alton wears jacket and pants by HOMME PLISSÉ ISSEY MIYAKE and trinity rings by CARTIER.

MS: That’s funny because when Mingus [Murray, Ming’s son] was young—about 15 or 20 years ago—he asked me for $20. And he said, “Mom, you’re in the Museum of Modern Art, and you don’t have $20?”

AM: That is funny.

MS: When I was first collected by the Museum of Modern Art, it was like winning an Academy Award and no one knowing about it. The few people that knew, there was a huge amount of jealousy; they weren’t necessarily my friends, because I lost a lot of my little group of friends and main supporters during the AIDS epidemic, and I received this award around that period. It was like when we had the pandemic recently, that’s what everyone was talking about then: losing our friends. So being in the Museum of Modern Art, well, it didn’t mean that much, but it meant something to me. It gave me justification for doing my work. I was thankful. I had validation. You were telling me, when you walk, you have validation. That’s a lot to help move forward. Who knows if I would have continued years and years and years if I hadn’t had that.

AM: Mm-hmm.

Alton wears skirt and pants by BOTTEGA VENETA.

MS: I traveled a lot when I was married to a jazz musician [David Murray]. Although I traveled a lot before that: I went to Paris and was the first L’Oréal ambassador to be a Black girl. But when I was traveling with my ex, I was a wife, and I would go because I would search out dance teachers. And I would look for Katherine; she used to travel all over with her troupe. They loved her in Europe.

AM: Traveling definitely made me who I am. My dad played pro-ball overseas. And he had me at like 17 or 18, so he and my mom were very young when they had me.

MS: So, you went overseas, too?

AM: Yeah. We first moved to Arizona when I was 1, so that’s where I’m from. Then we moved overseas to Tournai to play in Belgium. We lived in the Czech Republic, Greece, Amsterdam, Germany, and Bosnia. He played in 11 different countries until I was about 13. Then we settled in Arizona, and I started going to high school there. It definitely opened my eyes to a lot of self-awareness, gave me a lot of enlightenment on relationships and friendships—how to keep in touch with someone. All of that can definitely shape a human. Luckily I have parents who were big on values.

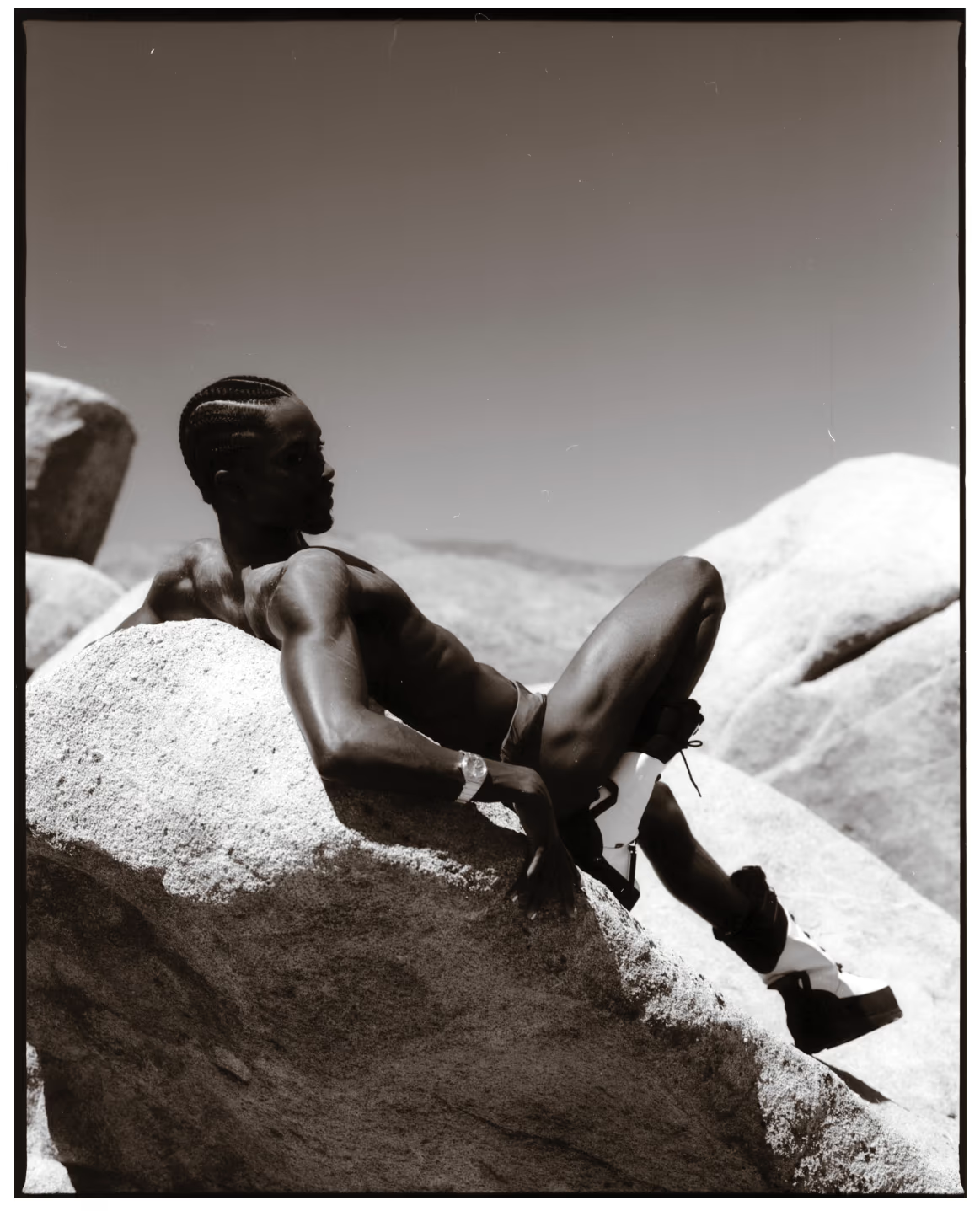

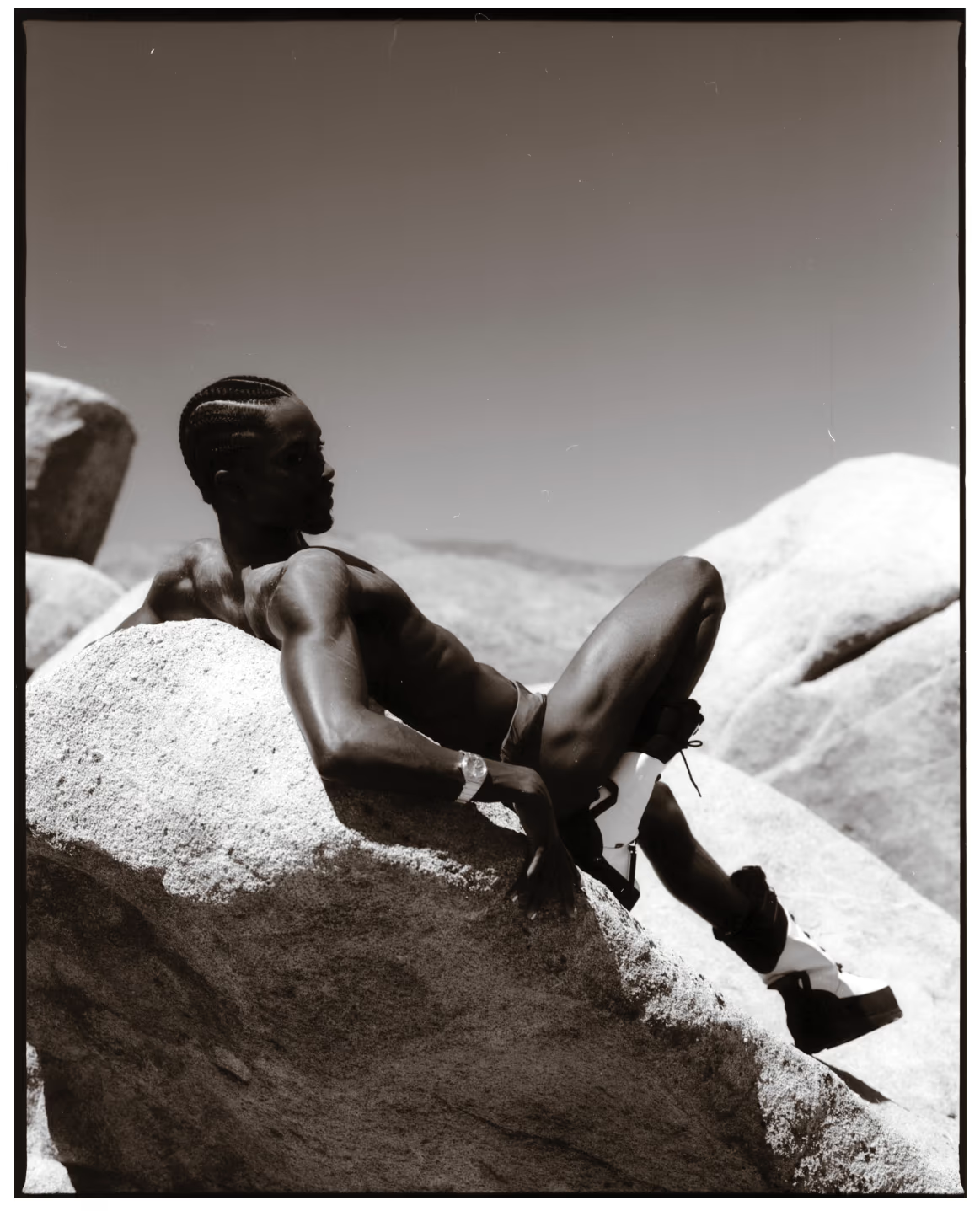

Alton wears boots by UGG and watch by OMEGA.

MS: That’s great. So many people have mothers and fathers who are not supportive or not in the picture at all. So that’s nice that your parents were there for you. Plus they gave you that home training. You have a spiritual base to rely on.

AM: It’s everything.

MS: You know in the older African cultures, dance and music were part of everyday living. They understood that. So creating, the way they just did things is traditional. Here in America, we don’t have that. It’s always good to have some spiritual connection, whether it’s meditation or your relationship with God: It’s really the only thing you can depend on.

Alton wears coat, pants, and tie by GUCCI.

AM: Gratitude is the highest vibration after music and dance.

MS: Really? I didn’t know that.

AM: Gratitude is the one, so I’m happy that I have inherited it.

Talent ALTON MASON at IMG.

Hair Stylist STARSHA APPLING using THE DOUX PRODUCTS.

Makeup Artist ZAHEER SUKHNANDAN using MAC COSMETICS.

Photo Assistant VICTOR ALVAREZ.

Fashion Assistant BLAIR CANNON.

Production LUKE O’SULLIVAN at LUCID PRODUCTIONS.

Production Assistant ANTONIO CAVALLO.

Special Thanks SD(MGMT).

.avif)