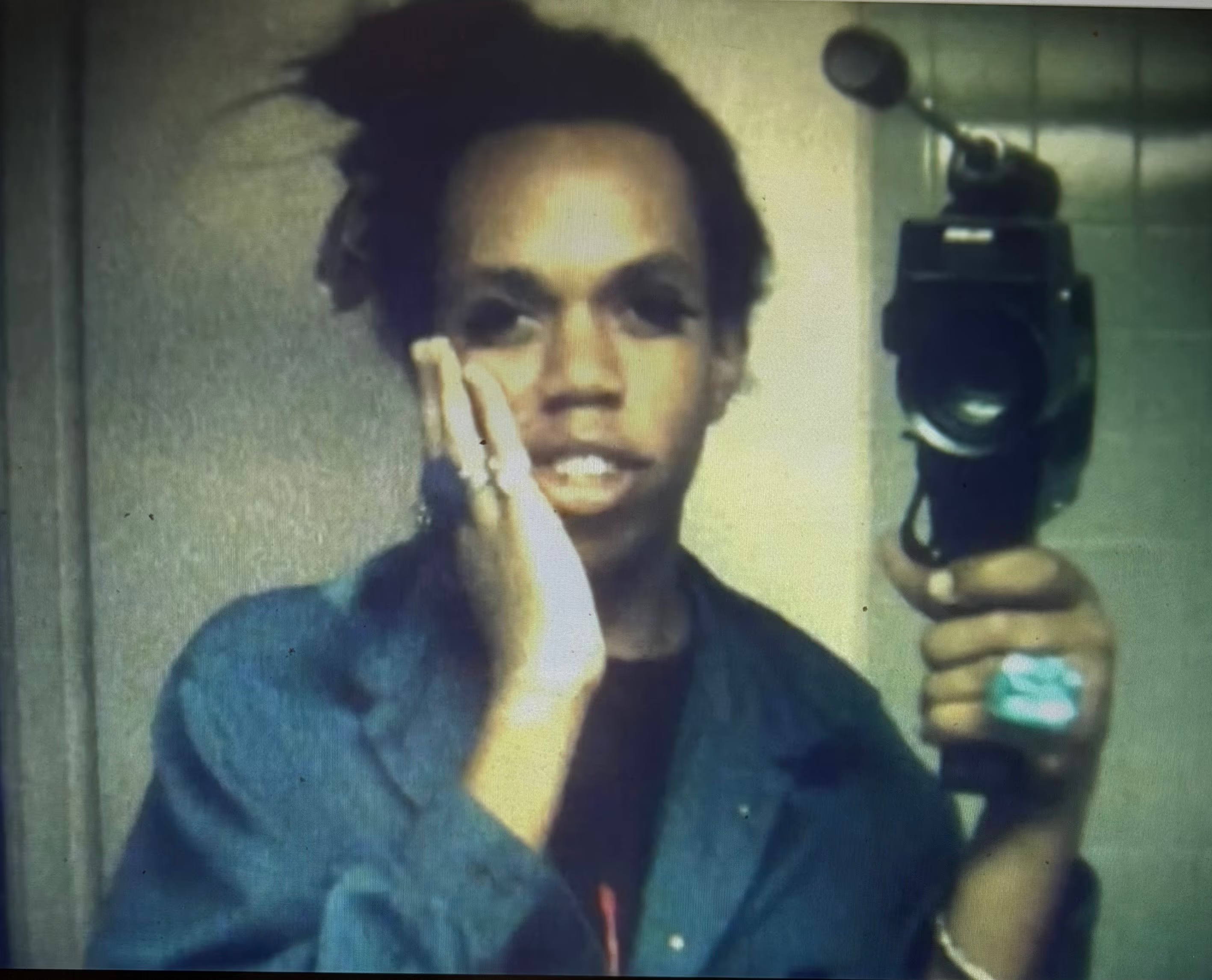

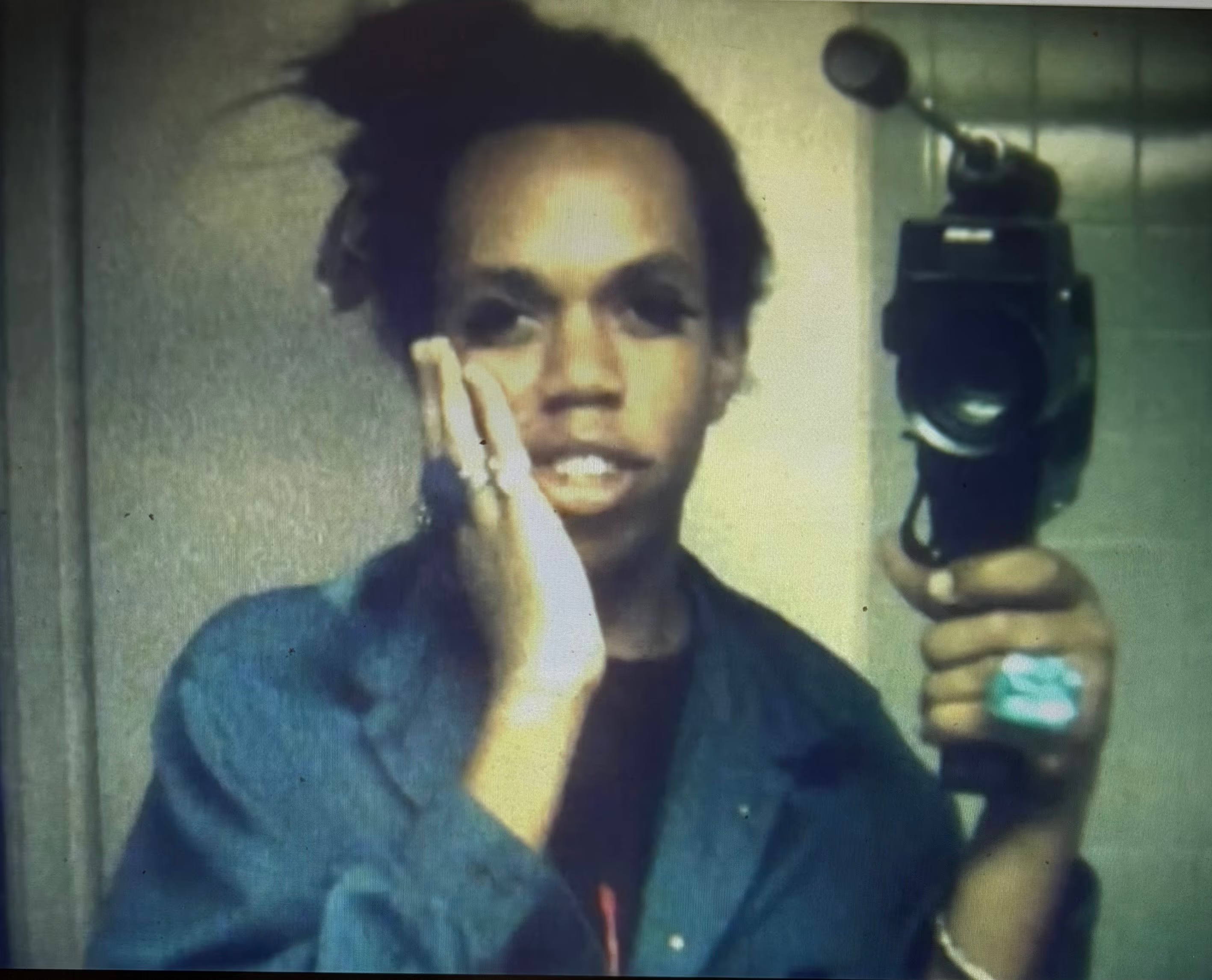

Image courtesy of Brontez Purnell.

Sean DeLear was the original Black Valley girl. Legend has it, she was among the first group of LA punks to populate the then-newly forming first wave. Like far too many artists, DeLear, who used he/she pronouns interchangeably, was awarded her flowers posthumously—she passed away in Vienna in 2017.

I had the pleasure of being friends with DeLear myself. She had to be the most dapper dresser in the world, glamour oozing from her pores. If she had not slummed it with the punks, she could have easily passed for a ’60s underground movie star. Simply by being in her orbit, you felt beautiful, too, like her radiance was transferable. Above all, she was one of the most captivating storytellers I have ever encountered. I would sit by her side, spellbound by her every word about the LA scene of yesteryear.

Our first encounter was in the aughts, in a warehouse space being converted into a mansion across the street from the Eagle LA. We stayed up all night talking. It was nothing short of inspiring to meet another queer, Black punk, albeit older than me, who was so very generous and captivating.

We met through LA-scene veteran Mike Hoffman, who is one of the executive producers for The Life of Sean DeLear (2024), an utterly moving, kaleidoscopic, and dreamingly disjointed documentary by Markus Zizenbacher with music by Mike Watt of Minutemen fame. The documentary starts on a rather somber tone, revealing DeLear’s deeply religious mother and brother at a table reflecting on the late artist’s life. In the next clip, her brother, now an Evangelical pastor, discusses his own struggles. DeLear’s was the first Black family to move to Simi Valley, California in the late ’60s. As a teenager, she would hitchhike the more than 40 miles from the suburb to Los Angeles to catch punk shows in Hollywood. She’d chronicle those adventures in her diary, published in 2023 as the book I Could Not Believe It.

Punk rock, of course, has certain ethno-cultural religious undertones. DeLear’s time as lead singer in LA post-punk and power-pop band Glue looms large in her history. Reportedly, the band’s video for its single “Polara” debuted on MTV’s 120 Minutes (1986–2000), but it was immediately pulled after a higher-up was not too happy to see a Black drag queen front woman. It would make sense that DeLear, who was born Anthony Robertson, would invent a church of her own and self-fashion herself as high priestess of it. In footage from 1986, she poses in the back of a pickup truck, wearing a ’60s paisley dress, long hair, and signature lashes.

Image courtesy of Brontez Purnell.

Even in the face of challenges, she carried a bold sense of forwardness and defiance. She never let the weight of the world crush her. Every scene in The Life of Sean DeLear is lighthearted—even archival footage self-shot from the ’90s, where she appears to almost get into a physical altercation with a doorman. You can’t keep a good bitch down, and DeLear proved it through fashion, candor, and art-making. Her can-do attitude is infectious and inspiring.

We are in a period of unearthing past unsung legacies, but perhaps more revelatory now than ever, DeLear’s life hits the marks of a hidden time. It is not fair that her story was so obscured to us when she walked the Earth so boldly. Her life was deemed “marginal,” but DeLear was the center of everything. She was born a star, remained a star, died a star, and posthumously remains a tributary to so many of the freedoms we now see. Drag Race being popular T.V., the Afropunk movement—these are things that could be only dreamed of in DeLear’s day. The true mark of a documentary about the deceased, I think, is that one should leave feeling like the subject is a part of them. DeLear’s larger-than-life persona leaps out of the screen in a truly infectious mix of both playful beauty, defiance, and her approach to life as if she were the queen of the goddamn world, which by the time the film ends, one understands she certainly was.

Considering her legacy more broadly, I can’t help but ruminate on why her star didn’t ascend higher in her lifetime. For all practical reasons, DeLear should have, or at least could have, been a punk rock counterpart to RuPaul—all the elements were there. But in confronting DeLear’s queerness and Blackness set against the very white and masculine scene of LA at the time, one can easily imagine the hurdles she faced. That said, her presence in the city was not one of “outsider artist.” Rather, she was the scene personified. Yet no subculture exists in a vacuum, and no matter how liberatory it purports to be, it is still half Earth-bound. DeLear’s career sat in such a liminal place for disappointingly obvious reasons. Punk rock, though in large parts defined by its gender-bending anarchism, simply wasn’t ready for a Black drag queen. But that didn’t discourage her.

.avif)