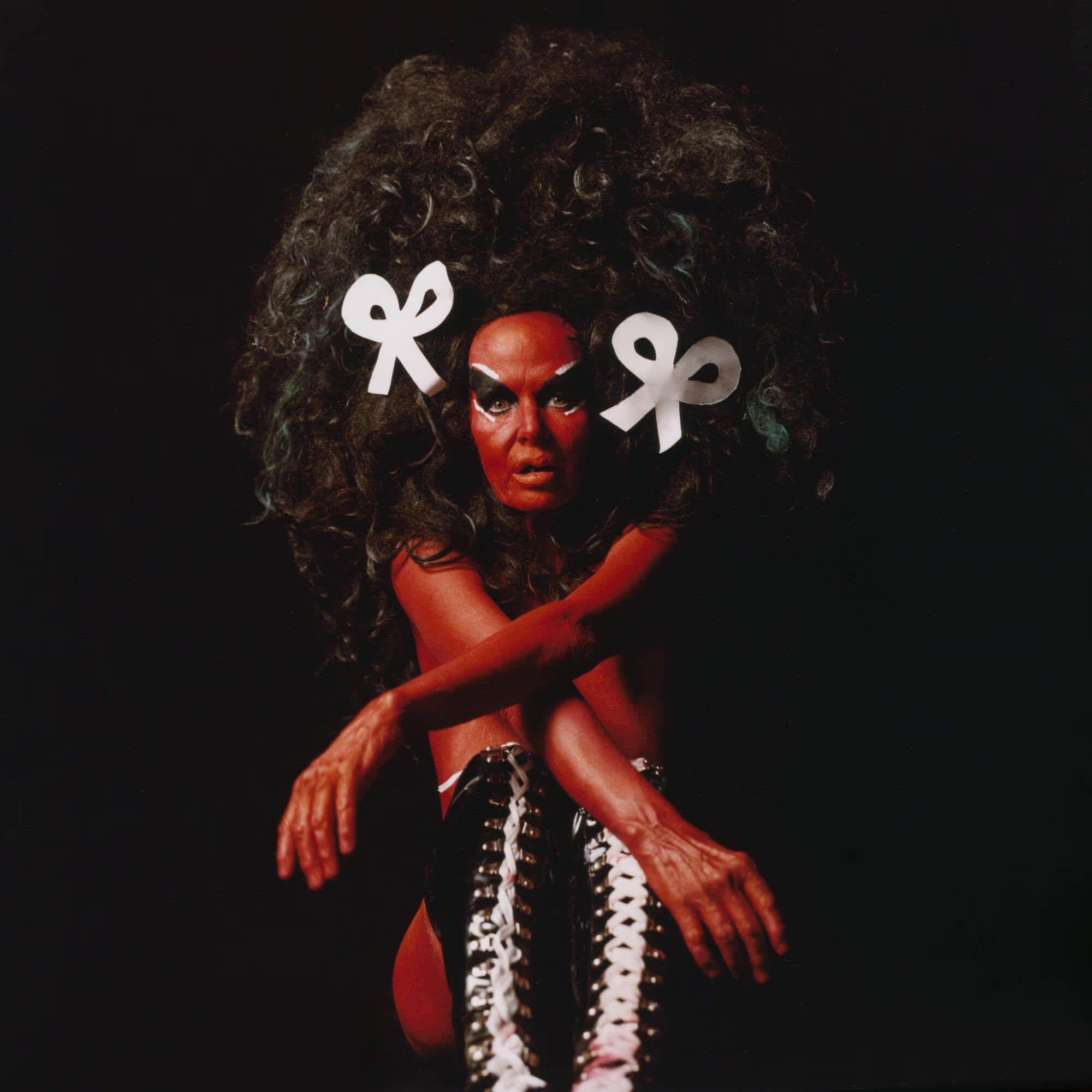

As the frontwoman of death-rock band the Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black, Kembra Pfahler has built a cult following with her visceral blend of music, performance art, and striking visual imagery, all while fearlessly exploring themes of feminism, the body, and the grotesque. To those in the know, she’s instantly recognizable for the vivid layers of frightly paint she coats her body with and the generous mane of curls and dainty bow ties that sit atop her head. It’s a look she reflects in her children, too—both the miniature replicas just as glam rock as their mother, and in her countless human disciples whom she dresses in her image. Since she moved to the city from Los Angeles in 1979, the artist, 63, has made her mark in New York as a critical persona in the punk art and music scene, a coveted status of true greatness attained by the brave, those who readily go where few will dare. Her work is a statement—a riotous challenge to societal norms and expectations.

Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez, the creative duo behind Proenza Schouler, share this radical devotion to the narrative. Since they established their brand in 2002, the two have been at the forefront of the fashion industry, crafting thoughtful work that walks the thin line between pop and high art.

What happens when an art world provocateur and a visionary label collide? A seismic shift occurs. When Pfahler and Proenza Schouler joined forces in 2009 for Pitti Immagine in Florence, it was no regular fashion show: It was a concrete meeting of punk sensibility, performance, and high fashion. Their explosive synergy caught the audience by surprise. The collaboration was a direct challenge to the limitations of conventional art, with Pfahler’s wild style fusing with the label’s aesthetic of refined rebellion. But McCollough and Hernandez’s connection to New York artists is more than a casual engagement; it has become a close relationship that informs their creative process. The pair have always searched for inspiration from within the city’s diverse artistic milieu, often teaming up with its audacious creators to set fashion ablaze. In New York, where both Proenza Schouler and Pfahler call home, the formidable forces come together to discuss their first collaboration, where counterculture has gone, and tough criticism.

Lazaro Hernandez: Hi Kembra!

Jack Mcollough: Long time no see!

Kembra Pfahler: I was missing you both.

LH: I know, it’s been ages.

KP: You know how some surfers remember every wave they ever ride? For some reason, I remember all of my performances in extreme detail. I remember going to your design office for our series at Palazzo Pitti. I remember talking to you about having a tiered chorus of women of Karen Black, and you all organized a ballet company from Italy to participate in the performance. There were at least 30 kids and 30 women all dressed up. We were wearing these maroon-and-white striped outfits that you made for us. You made me a black one-piece corset, and I built props and made dolls.

JM: We have one of those dolls still somewhere in the house! My parents came, and they were very confused and slightly offended. That meant it all went well.

LH: It was wild. I don’t know who let us do that. We said, “We don’t want to do a fashion show; let’s make it a happening.” And [Pitti Immagine] let us invite all our friends, and they flew us out. Do you remember, we flew with Chloë Sevigny, Jack?

JM: Yeah, I was impressed by the freedom they gave us to put together whatever we wanted.

KP: I’m not very European, so I was in a state of shock being in Italy. I never really experienced all those strange things that happen in Europe before. Whenever I go there now, it’s like visiting a horror film. I’ve never been able to get over World War II, and everything just feels like a bomb site that’s been covered over.

LH: We’ve been spending more time in Europe lately. There’s something magical about it again in our universe of fashion.

JM: Less is happening in New York these days, which makes me so sad because New York used to have this amazing energy around it.

LH: I don’t know if it’s a creativity problem... New York is the epicenter of creativity; it always has been.

JM: Of course, but within fashion, it just feels like a more commercial endeavor here.

KP: Definitely. I mean, I started teaching around 2010...

LH: Where?

KP: All over. Bard, CalArts, I taught art and music at Columbia [University]. The students were so stressed out. I think being that competitive can kill your spirit. Something happens when there’s that intense commodification of fashion and art. It feels like art right now is just decorating rich people’s houses. There’s only one type of artwork that’s really selling—oil paintings. A lot of galleries have been blowing up and then popping, disappearing. I don’t feel like there’s a lack of creativity in fashion or art so much as these are just such harsh times for new people.

JM: Expenses in the city...it’s out of control how pricey everything is. I think a lot of people want to jump straight into their thing before they go work for someone else, which is kind of what we did but now that’s just everyone’s M.O.

LH: Back in the day people wanted indie stuff: indie designers, indie music, and indie film. Now the weirdest thing has happened: All the kids just want the same thing. They all want the same bag, the same kind of shoe by the same brand owned by one of those humongous conglomerates. All the movies have become these comic-book Marvel movies, and everyone wants to look the same.

KP: I still see that type of independent outsider, but I guess we’re all noticing that it’s a very small group of people. There’s always going to be strange little pockets of people holding a golden key to the underground. It’s just more niche now.

LH: A lot of independent voices no longer have a big audience. Breaking out has become harder and harder.

KP: I think with you guys—I can say this about myself, too—making it look easy has always been something that comes naturally. As hard as it has been, it’s also been so much fun to be able to do my own work. There’s not a lot of discussion, really, about the sacrifices that you make, how difficult things are.

LH: Oh, we hear you on that one.

KP: In a way, I’ve had a proclivity to make things look easy because I’m always talking about how, no matter what, you can work with what’s available. If you’re living in an urban city, it’s your job to fight your way towards greater creativity. I haven’t really been forthright about how intensely difficult that’s been.

LH: I think we don’t want to talk about those hard periods because you want it to feel effortless. If we can be forthright about how it’s not fucking easy—that it’s really hard to stay independent and be creative—I think that’s good for kids to hear.

JM: One of the things that’s kept us going over all these years is that we’re our own worst critics. The minute we finish something and put it out there, it’s in our process to pick it apart and find all the things that were wrong with it. And that leads us to the next thing. It makes us want to do better and try to redeem ourselves, to destroy it and move on.

KP: There’s so much freedom in inventing your own holistic timeline. Fashion schedules are far more punishing than a performance artist’s schedule or an exhibiting artist’s schedule or a rock ‘n’ roll band’s schedule. You can still exist as a musician and you don’t have to play at South by Southwest; you don’t have to be a Grammy-winning singer to participate in the music world. Did you see that film about Simone Biles?

JM: I heard it was incredible. I want to see it.

KP: She was talking about how she quit at the Tokyo Olympics because her mind wasn’t connecting with her body, and she could have really harmed herself if she continued to compete. The way she described this mental process as “the twisties” is so applicable to what artists and fashion people go through, and those twisties have to be recognized. They have to be honored, and it’s very painful. I’m sure in your business you’ve been told that if you miss a couple of seasons, you’ll ruin your lives forever.

JM: You’d become irrelevant.

KP: It’s such bullshit because you’re the ones that are creating.

LH: Sometimes I think it’s better to disappear for a minute and come back. Rather than being in everyone’s face 24/7.

KP: Actors do that really well. Designers sadly don’t have the opportunity to do that, or they think they don’t have the opportunity to do that. But sometimes it’s good to peace out for a little bit, and then everyone will be so excited to have you back to see what you have to say.

JM: Do you feel like your audience has changed over the last few years?

KP: One of the things that has helped me remain uplifted is having a strong sense of community and a very important friend circle that enjoys working together. And I’ve had that decade after decade. I’ve been really lucky. Because of teaching, there’s still a small group of people who are interested in what I do.

“There’s always going to be strange little pockets of people holding a golden key to the underground.”

— Kembra Pfahler

JM: People are so much more collaborative in art than in fashion, where people are more competitive.

KP: Rick Owens has always been the kind of designer who always has encouraged me to meet other designers. If I say to him “Oh, I met Jack and Lazaro,” or, “I met people from Valentino,” or, “I met people from Calvin Klein,” or Thierry Mugler or something, he’s always excited. I got to do this capsule collection with him this year. It took six years for me to design it. I kept doing these strange drawings, and he would very politely get back to me and say, “Kembra, I don’t think the people in Italy at the factory are going to be able to understand your Flintstone-type drawings.”

LH: Six years for a collection...

JM: I wish we had that lull.

KP: I know, you guys must just blink. It’s so little time.

JM: It’s weird though. You start to get used to it. And then too much time, I think, is a curse in our industry. You want to get a feeling out there, and oftentimes what we’re trying to succeed at is speaking to the times we’re living in right now. If we sit on that for too long, it can start to feel less relevant. But it would always be nice to have an extra month...

KP: Well, then does it lead into the next collection?

LH: Yeah. There was a time when we would dive into a creative world and become obsessed with whatever it is, like Kenneth Anger or Boyd Rice, and create a collection based on that feeling. When that’s done, you don’t want to think about it anymore, so you throw it all away and start completely new. Now, we’re trying this run-on sentence approach, where things can exist between collections a little more seamlessly.

JM: We have a lot of things that feel like unfinished paintings laying around that we can come back to.

KP: I was looking at a genetically modified rose the other day. It was a red and orange rose, and I thought to myself, This is the future of humanity as well. We’re able to mutate and alter the way human beings are born and what kind of human beings are being born and what kind of consciousness we can upload into their brains. I mean, it’s so bizarre. Everything that was a science-fiction horror prophecy is actually coming true, all those Philip K. Dick stories, like Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?. And A.I. is so laughable right now. Can’t you always tell when people have used A.I.?

LH: You can tell when the language isn’t quite right. Designers are using it as a starting-off point.

KP: I don’t use the computer very often at all. Do you have friends that say, “I’m never on Instagram,” but they are actually always on it? I really don’t look at social media very often at all. And I don’t look at things online very often, either. So usually it’s all some kind of terrible weird surprise to me. When I see things, I’m wondering, Oh, is that really happening? Do I really think that Kamala Harris is writing to me? And I apologize for not giving her $10 for her campaign. Can I Venmo you Kamala? I just heard this morning about how Trump wants to be president for the rest of his life.

JM: You can’t make this shit up.

KP: It’s so bonkers, right? It’s been a really surreal past 10 years. I mean, that’s not an exaggeration. I’m 63 now. Getting into that Karen Black costume can be so horrifying. There’s really not that many people that I will work with these days; I have to honor my physical experience. It’s such a privilege to be able to work decade after decade. That, to me, is living an extreme life, just to be able to participate in culture at all, no matter if it’s in a very small way or a loud way. When I was in England, everyone would always ask me if there was any hope for the future. And I was like, “Why are you asking me, specifically?”

.avif)