Near the beachfront of a tiny Tuscan village, a dinosaur stands with its head emerging from a pool of water. Its brontosaurus neck gently curves up to a massive zeppelin-shaped body atop legs as thick as tree trunks—a colossus of a beast, ensconced by the coastal woods. The primordial creature, constructed out of cement and wire netting with a hollow in its core that forms an orb of a living space, is one of the most radical homes in Italy. Here, Casa Dinosauro appears more like a figment of a child’s imagination than a functional residence. With its iconoclastic architecture, the house’s affinity with nature resonates more urgently than ever as we rethink our impact on the planet.

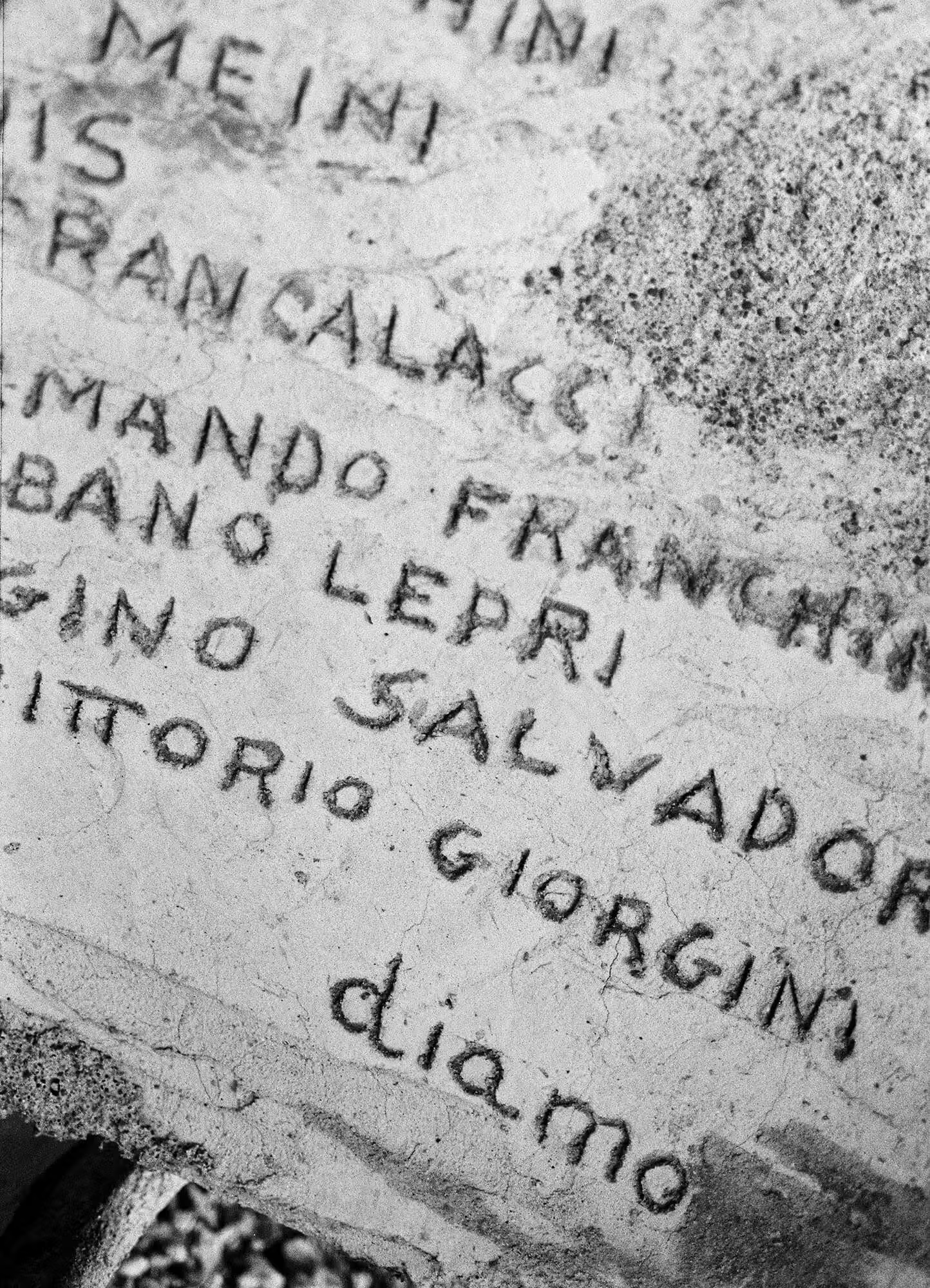

As the story goes, the dwelling’s creator, Vittorio Giorgini, was once sailing through the Gulf of Baratti when he encountered a storm and was forced to dock. Finding himself safe on dry land, he fell in love with the old and undeveloped locale, framed by wild foliage, where he would eventually build two residences—outliers in Baratti, a mere hamlet with just 15 inhabitants and little cultural flourishing since the Etruscans settled the spot in ancient times.

Giorgini built his summertime home, Casa Esagono, first. Finished in 1957, it is a honeycomb arrangement of six hexagonal wood wings surrounding a central room. It was here that the architect sat on the veranda with his friend, the industrialist Salvatore Saldarini, looked out to the sea, and sketched out a rough draft of Casa Dinosauro, which was to be built on the neighboring plot of land.

Captivated by his friend’s notions of architecture in harmony with the landscape, Saldarini offered to pay for the experimental construction, though Giorgini informed him

that he couldn’t guarantee it would stay up. Saldarini, who’d made his fortune in the silk industry, gamely replied that he would consider it an expense lost due to risk, should the house collapse.

In the end, the pair both won, as Casa Dinosauro has endured since it was finished in 1962. To construct the groundbreaking home, Giorgini employed the nearly untested technique of spraying concrete over a sinuous arc-welded mesh frame to create the kind of free-flowing organic form that had only just started to appear in architecture. The material was shaped by hand in places, the rough five-centimeter-thick surface embedded with seashells, brick fragments, and shards of Etruscan pottery. The interior curves differ from the outer zoomorphic shape with a separate frame that ingeniously allows for insulation and airflow. Giorgini designed his projects in accordance with nature, believing humans should leave the world better than they found it—but he also believed nature to be the source of the most practical solutions possible, and his improbable habitation turned out to be more efficient and more cost-effective than typical straight-lined houses.

“Like a nautilus shell or a bird’s nest, curvilinear structures are more adapted to life,” says Luca Sgorbini, the current owner of Casa Dinosauro. His father, Leandro Sgorbini, an engineer who kept a boat at the port, discovered the property in a derelict state in 1977. The door had been left open, and wild animals inhabited the space after its previous residents had abandoned it, but Leandro was instantly enamored despite the many obstacles. “The house was at the limits of livability. Baratti was a no-man’s-land,” recalls Luca. “Everyone took my parents for crazy people for buying this abandoned house in the woods.” Soon after

Leandro purchased the building, he reached Giorgini by phone and even acquired some of his original sketches. The new owner quickly got to work installing indoor plumbing and electricity in the house to render it livable once again. Years later, the dinosaur exterior has remained intact while the interiors have been restored to their original appearance.

“I’m a doctor—I didn’t know anything about restoring something like this, but it’s a place that casts a spell on you,” says Luca of the ambitious project that he inherited from his late father. Cabinets, benches for seating, and a raindrop-shaped fireplace that had been built right into the undulating concrete walls have remained intact, but other furnishings have been destroyed, and carpeting that had begun to mold was replaced with a terracotta floor. Today, the floors have been restored to a raw concrete expanse. With this, newly added partial walls, constructed using the original sprayed-cement technique, create room dividers in the cave-like space—an aspect envisioned by Giorgini himself, but never before realized.

These renovations were guided by Marco Del Francia, the architect who served as Giorgini’s assistant for 13 years until the older master died in 2010, and who was part of the team that restored Casa Esagono, too. Today, Del Francia heads B.A.Co., the Vittorio Giorgini archive. “Everything I could say seemed banal compared to his way

of thinking,” he says, admitting that even he was daunted by the presence of his predecessor. “Giorgini didn’t limit himself to conceiving of architecture in relation to the earth. He was thinking about how everything had to vibrate in harmony with the entire universe.”

Influenced by architects and thinkers who built in sync with nature—from Le Corbusier and Antoni Gaudí to Frank Lloyd Wright and even Rudolf Steiner—Giorgini nevertheless lost credibility in Italy for his experiments in Baratti. He did, however, gain respect for his work abroad; it was exhibited by the Museum of Modern Art and acquired by the Centre Pompidou, and he even got a teaching job in the architecture department at the Pratt Institute. It wasn’t until more than a decade after his passing, though, when he was featured in the 2021 Venice Biennale, that Giorgini finally found recognition in his homeland. “He was a person too advanced for his times and his native country,” says Del Francia. “Giorgini articulated notions that are finally very much in vogue today, thanks to the relevance of sustainability.”

Yet, in mid-1960s Baratti, Casa Dinosauro, with its swooping monumental form that looked nothing like what had previously been projected as a house, seemed more outlandish than avant garde. Giorgini sold Casa Esagono before leaving for America, and Saldarini ceased visiting Casa Dinosauro. Nevertheless, Giorgini returned to Italy for the later years of his life, and his ashes were spread in the Gulf of Baratti.

Today, Casa Dinosauro is a testament to a time when visionary ideas could seamlessly translate to unencumbered expressions of wild creativity, all the while

articulating concepts that retain a sense of forward-thinking innovation. A house may be intended for day-to-day existence—but, in Giorgini’s hands, it expressed something much larger: an affinity with all of life on our planet, resonating with the awareness we so desperately need to carry on for the future.

Special Thanks DAVIDE PRETTO and ELISABETTA BRICE.

.avif)

.avif)