The schism between us. Such a heady assertion intimates the inherent tension between “self” and “other”: the disavowal, the refusal, and the threat, real or not, of rejection! Certainty clears its throat. Humility steps aside. There’s a natural force to be reckoned with, a potent provocation. Yet how might this dynamic reveal itself in the quietness of an image? Or in the dialectic between beauty and fashion, fashion and style? After all, these are terms, concepts that are always in process, pushing up against hidebound tradition, testing the parameters of social and cultural mores.

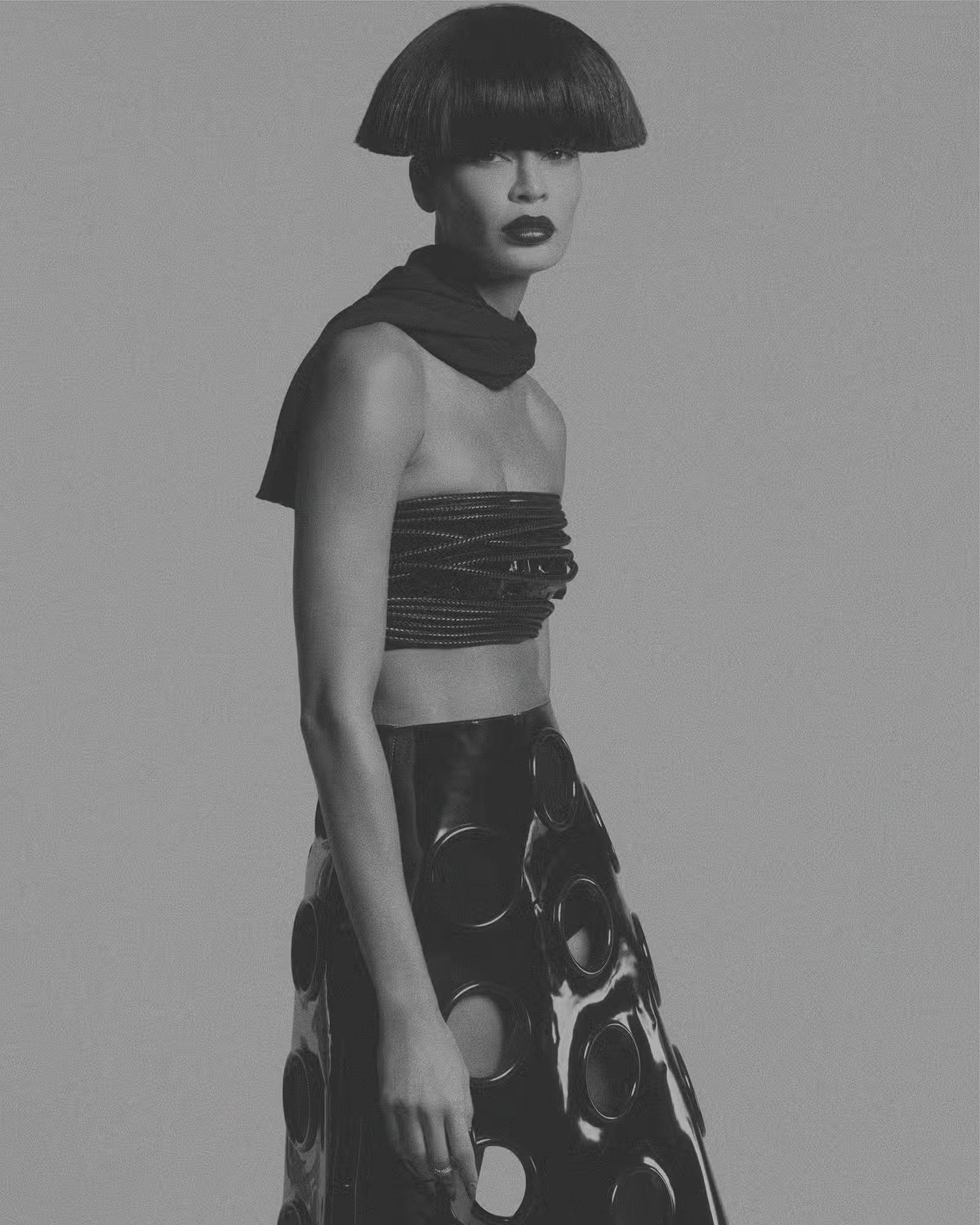

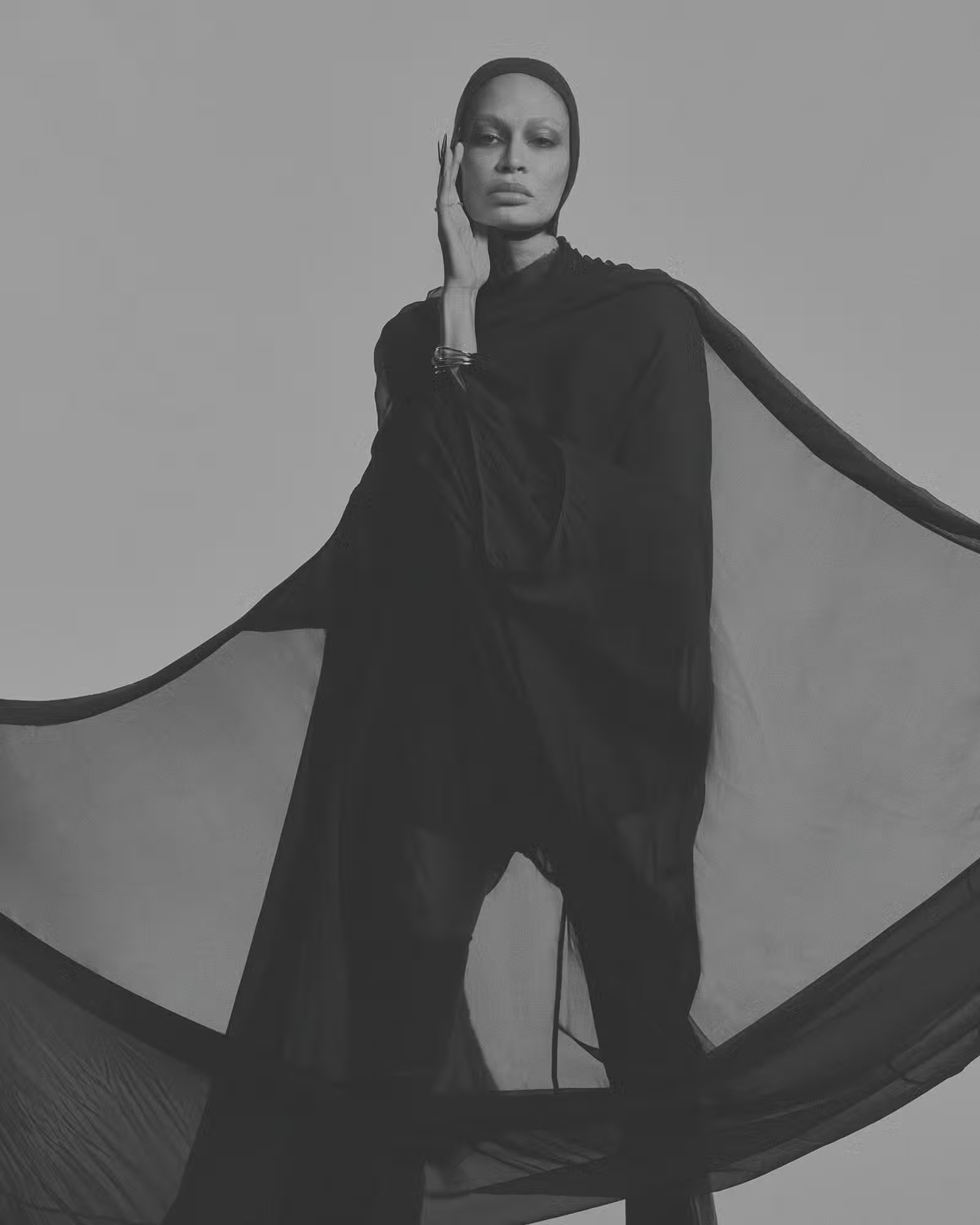

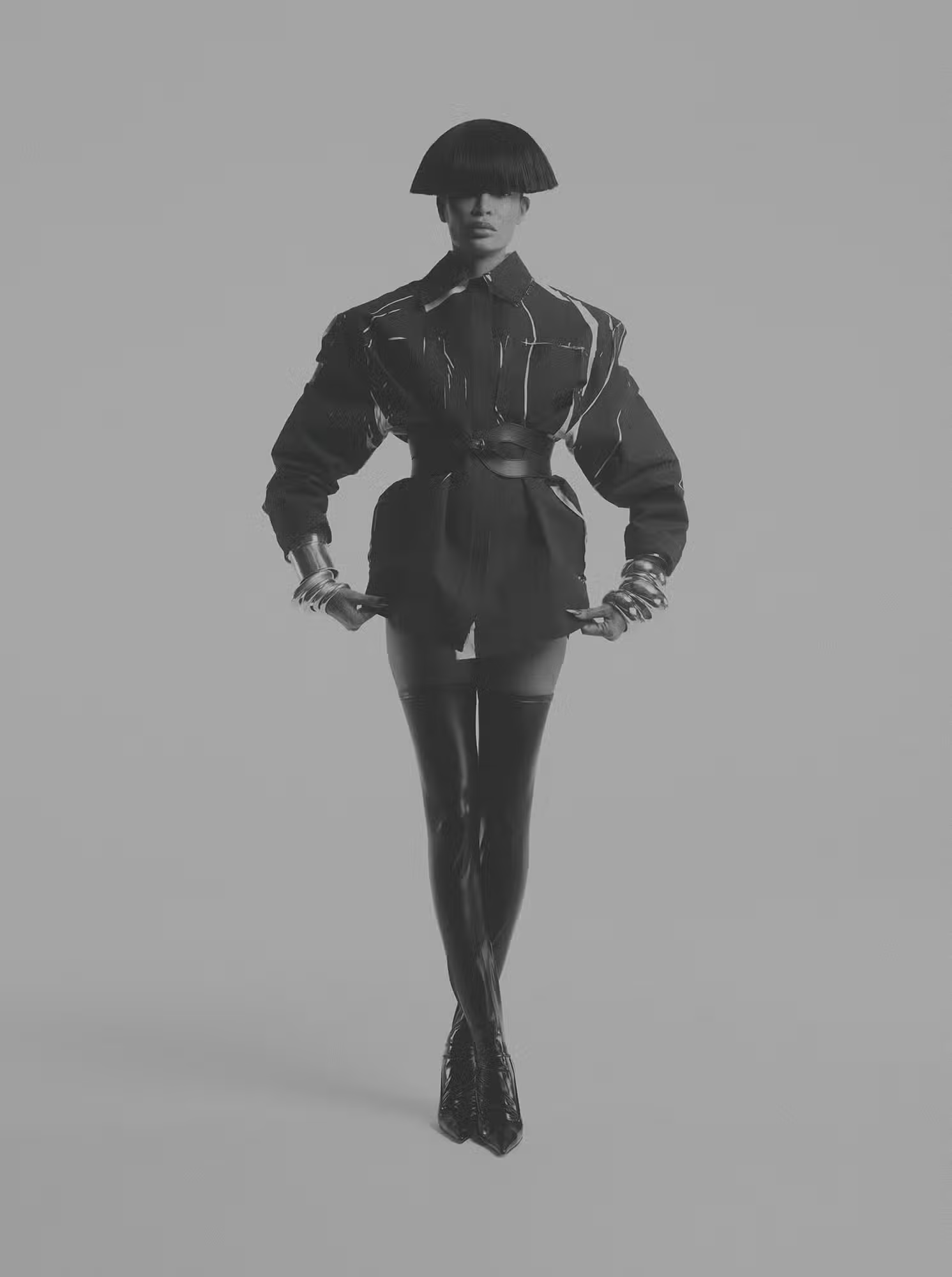

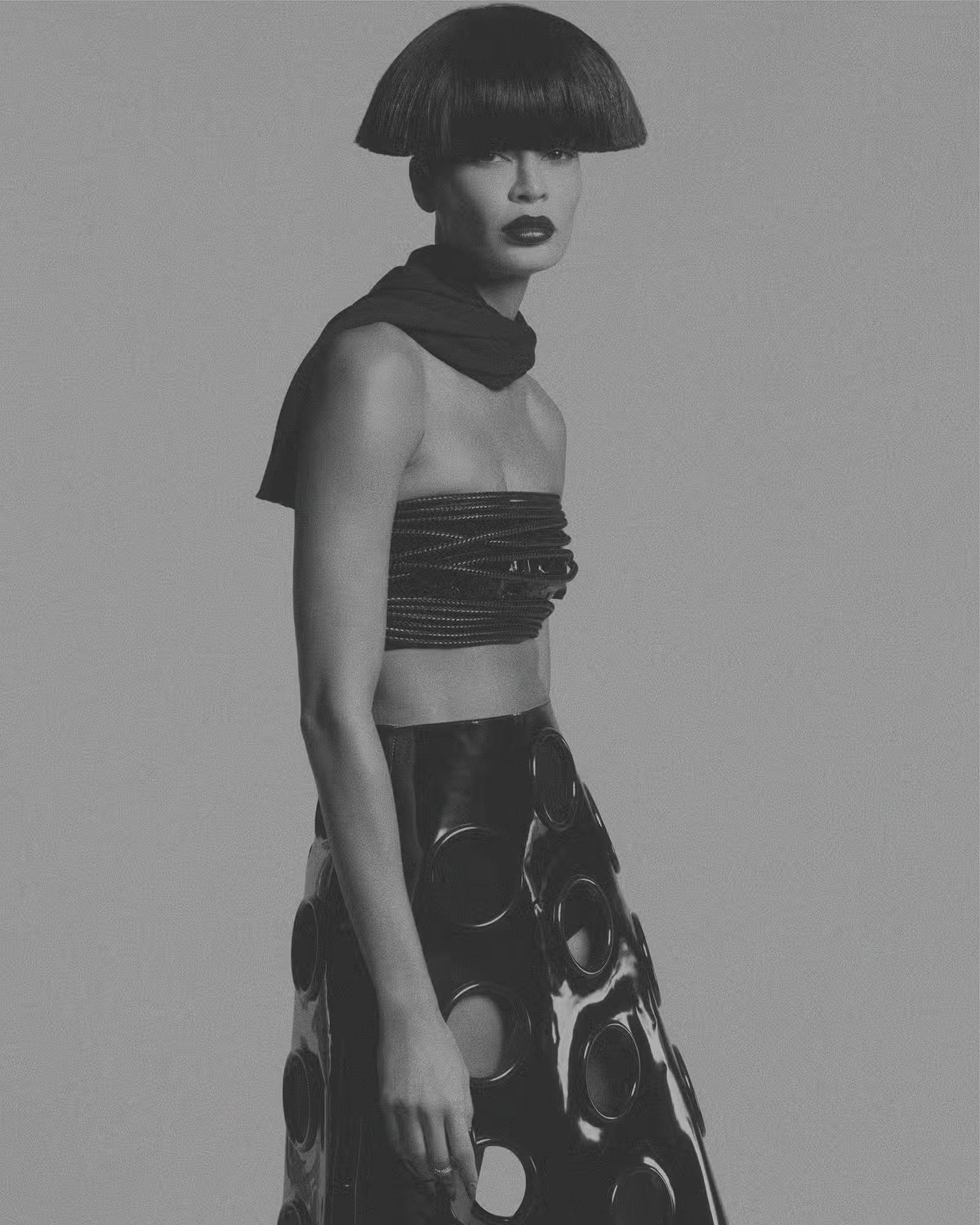

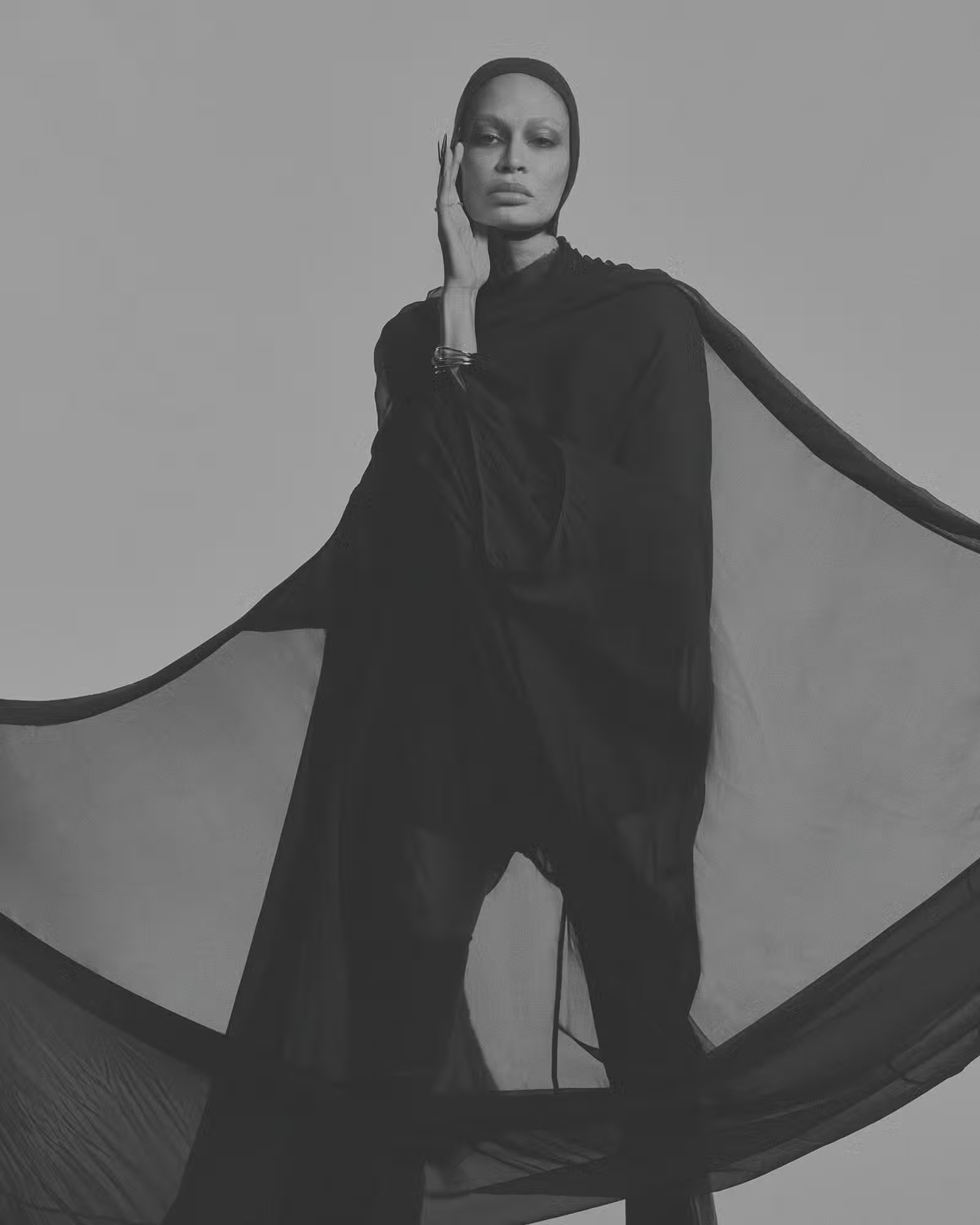

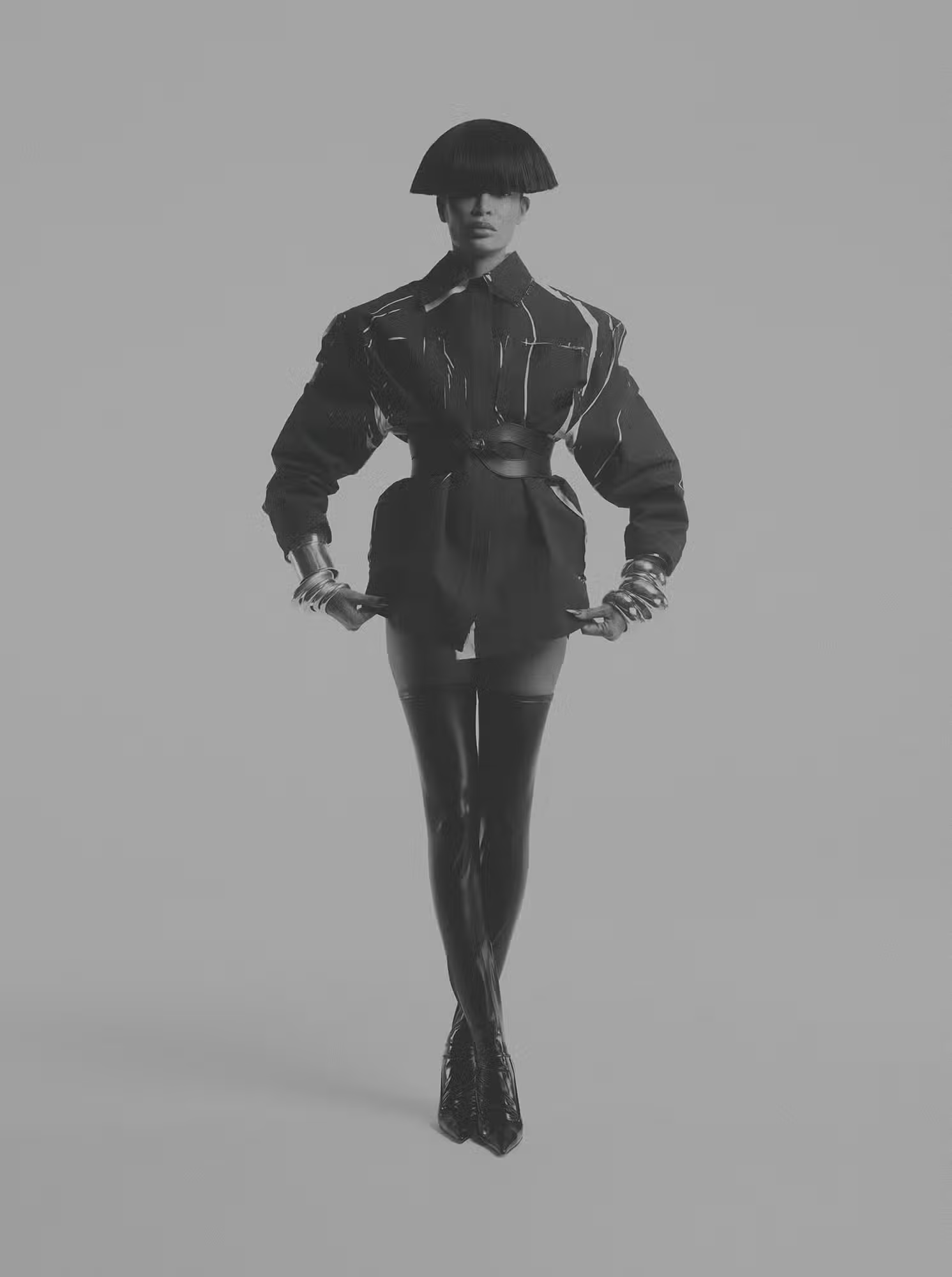

In the tussle between the “me” and the “you,” I’m reminded of the late Martinican writer Édouard Glissant’s “Poetics of Relation,” 1990, which rejects colonialist generalizations or totalities in favor of what he called “opacity”—referring to that which cannot easily be made legible for an ignorant audience. Similarly, Nadine Ijewere reminds us we are polyvocal in our gorgeous bearings, conveying multitudes in the magnetic worlds we conjure. Here, she pushes her lens into the realm of abstraction, envisioning the sublime Joan Smalls anew. The pose, the posture are offset against a muted backdrop, and the body cuts a figure that casts into sharp (or blurred) relief the very interplay between positive and negative space. The stance is strong, unapologetic, commanding. On and on, Smalls averts, deflects, and reclaims our gaze. Her dynamic is syncopated across the portfolio of images. It projects an erotic charge. The devil is clearly in the details of hard and soft, of shadow and sheen. There is a near-talismanic quality in the relationship between garment and skin, the layering of texture (or protection) of fabric with its own sense of motion. Hair functions as headdress, while a blue pigment bathing the skin throws surface and depth into question.

In this will to adorn, to embellish, we return to the ego, that relational “I” ever dependent upon another entity, the “me” versus “you,” the seer and the seen. The viewer engages with the “I” as a literal, singular element, its mythos tied up in the Masonic ideal of the all-seeing eye, or the Eye of Horus. We find an immediate adjacency in the cow horn icon of the Egyptian goddess Hathor, consort of Horus, god of the sky. Keeping with our psychoanalytic theme, it should come as no surprise that Sigmund Freud kept a small bronze figurine of Isis suckling her infant Horus on his desk. In this spectral light, the totemic never looked so good.

Joan Smalls wears jacket and earrings by CHANEL.

Joan wears coat by ALAÏA and earrings by PANCONESI.

Joan wears full look by KHAITE and earrings by DINOSAUR DESIGNS.

Joan wears dress by 16ARLINGTON and shoes by TOTEME.

Joan wears full look by SAINT LAURENT and watch by ROLEX.

Joan wears sweater and skirt by PRADA and ring by VAN CLEEF & ARPELS.

Joan wears full look by RICK OWENS and hat by HEATHER HUEY.

Joan wears full look by RICK OWENS and hat by HEATHER HUEY, and bracelets and rings by CARTIER.

Joan wears shirt by JASON WU, belt by VAINCOURT, shoes by JIMMY CHOO, and bangles by DINOSAUR DESIGNS.

Talent JOAN SMALLS at NO SMOKING.

Hair stylist MATT BENNS at CLM using K18.

Makeup artist GRACE AHN at DAYONE using MAC COSMETICS.

Manicurist EVA SURIATY.

Casting director NOAH SHELLEY at STREETERS.

Lighting director CHRISTOPHER SMITH.

Photo assistant JAMES GILBERT.

Digital technician ATARAH ATKINSON.

Fashion assistant ZAKKAI JONES.

Production THE CURATED.

Special thanks MINI TITLE.

.avif)