Andy Warhol’s face oscillates between the likeness of a skull or a mask in Gerard Malanga’s film Andy Warhol: Portraits of the Artist as a Young Man (1964-1965). Taken in the first years after Warhol opened the Factory, the film portrays the artist on the precipice of pop. “He was becoming the myth,” notes Anastasia James, a dedicated Warhol scholar and director of galleries and public art at the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust. But still, “you see a vulnerability in his face and the way he’s presenting himself,” James suggests. “Is he actually vulnerable?” I ask. “Or is he making himself be perceived as such, in the way that Marilyn would give a camera doe eyes…” James bursts into laughter, the morning sun beaming down on their face: “There is really no way to know.”

For the first time ever, the public will be able to watch this portrait on December 14 at Pittsburgh’s Harris Theater. The screening coincides with the release of Gerard Malanga: Secret Cinema, the first monograph of the artist’s work, co-edited by James and published by Waverly Press. That night, the theater will also premiere Film Notebooks (1964-1970), offering a sneak peek into Factory happenings, and The Filmmaker Records a Portion of His Life in the Month of August (1968), a visual diary with appearances from New York avant-gardists Marian Zazeela and La Monte Young. Three newly restored films by Roger Jacoby, a gay experimental filmmaker on the periphery of Warhol’s circle—Dream Sphinx Opera (1973), L’Amico Fried’s Glamorous Friends (1976), How to Be a Homosexual Part I (1980)—will also be shown. Jacoby’s films, which offer a glimpse into Pittsburgh’s art and film communities back then, are running on loop at Wood Street Galleries as part of Roger Jacoby: Pittsburgh Stories through January 5, 2025.

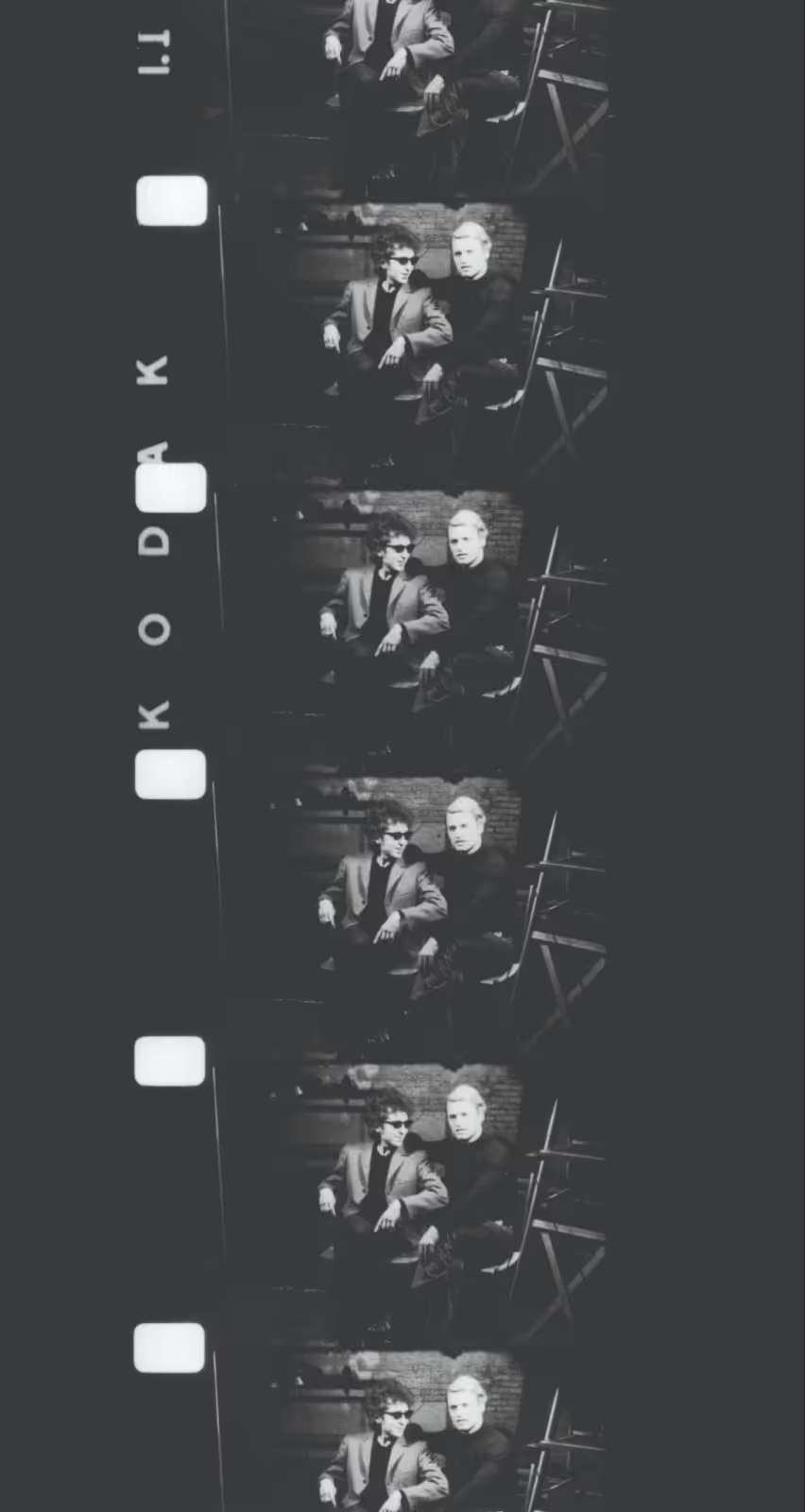

An artist in his own right, Malanga was integral to some of Warhol’s most famous works, from his films to his silkscreens. Together they shot 472 “Screen Tests.” He also acted in many of Warhol’s early films: Kiss (1963), Harlot (1964), Soap Opera (1964), Couch (1964), Vinyl (1965), Camp (1965), Chelsea Girls (1966), and Bufferin (1967). The only child of Italian immigrants, once a young man with dark, moppy hair like Mick Jagger’s and a taste for sharp suiting, Malanga embodied both the countercultural energy of the time and the polished, avant-garde style common within Warhol’s posse.

My curiosity about Malanga isn’t just about untangling him from Warhol’s shadow—it is also about seeing someone with a story rooted in a place I know so well. Like Malanga, I grew up in the Bronx, and very rarely do stories from the Bronx get told, especially in conversations about art and culture at this scale. His work, both alongside Warhol and beyond, is an indication of the untapped richness of such stories. His movies mirror how we now use moving images to preserve the mundane, but within the technological constraints of his time. Filming, as an action, came easy to Malanga, who was deeply influenced by Jean-Luc Godard’s naturalistic and intimate approach to directing and editing. “They were originally made as personal ‘film diaries,’” he explains. He was looking to preserve his own real-life moments on film for the future. That many were shot at the Factory—and that many feature Warhol—was simply a circumstance of Malanga working there.

In 1964, the Factory was where the avant-garde met its maker: Warhol, the great American artist whose mythology so often overshadowed the art he made, and the artists who worked for him. If the studio was the center of his universe, Malanga was one of its guiding stars. He is often referred to in history books, simply, as Warhol’s chief assistant. “This couldn’t be any more wrong. Malanga was one of the great interlocutors between the outside world and the inside world of the Factory,” James explains. “He and Billy Name were bringing all of these characters, these celebrities, these intellectuals, the poets, and the writers there.” It was Malanga, and others like him, who brought humanity to a space otherwise defined by its silver sheen and mythology.

“There are so many books, so many documentaries, about Warhol and his relationships. I’m more curious about humanizing these satellite figures,” elaborates James. Jacoby’s films, taken in the years following his involvement in the Factory scene, are surreal, often diaristic explorations of life as a gay man living in 1970s Pittsburgh post-Stonewall. Not as entrenched in Warhol’s life and work as Malanga, Jacoby was an artist and gallery assistant living in New York in the ‘60s who was drawn into the Factory one day by Billy Name. After tearing through New York, Jacoby and his long-time partner, Warhol superstar Ondine, settled in Pittsburgh during the 1970s. He devoted the rest of his short life to film, dying in 1985 at the age of 40 from complications related to AIDS.

Jacoby was a pioneer, bridging pre- and post-liberation gay experimental filmmaking. A tall, wiry figure with a pensive gaze and an unassuming air, his films mirrored his likeness. Like Malanga, his approach was both practical and deeply personal; he processed all of his own footage within the privacy of his bathroom, using his bathtub as a makeshift darkroom. Even the late filmmaker’s most seemingly straightforward work, How to Be a Homosexual Part I (1980), defied expectation in ways that were profoundly human. “A lot of people walked into the theater expecting a how-to guide,” James recalls Jacoby’s former partner Jim Hubbard telling them. Instead, the film offers a tender series of vignettes—candid portraits of his sister and mother, friends, and a couple from the Gay Activist Alliance. Reflecting on the film, James repeats the first three words of the title: “how to be.” “To me, that’s so powerful: to say, ‘This is what I’m going to document. I’m not going to tell you how to be; I’m going to show you,’” they say. This ethos of showing rather than telling underscores both Jacoby and Malanga’s unique ability to merge the personal with the political, presenting identity not as a finite directive but as a living, breathing thing.

That Marie Menken—a brilliant but often overlooked filmmaker—gave Jacoby his first camera in 1970 and mentored Malanga in the ‘60s feels serendipitous. Despite this connection, Malanga and Jacoby didn’t meet until 1971 when Ondine introduced them. “I made a photographic portrait of Roger and him on a stoop in Brooklyn Heights that winter,” Malanga shares, noting he didn’t see the two again until five years later. “When I started this project, my only goal was to stop referring to Jacoby as Ondine’s boyfriend,” James remarks, reflecting on the way one figure’s fame can overshadow another’s in historical narratives. It is the same with Malanga and Warhol. “I want to show how real these people were, how they had their own identities, and how much those identities influenced what transpired at the Factory.”

The artifacts James hones in on are markers of lives lived—a glimpse into a community of artists whose collaborations and interactions shaped culture. These fragments of history offer a peek into the energy and intimacy of spaces where art, film, and life collided in ways that continue to resonate. This act of recovery ensures that figures like Jacoby and Malanga are not relegated to footnotes but instead remain central to these conversations. The work becomes an offering not just to scholars but to anyone seeking to engage with the layers embedded within our collective memory.

For years, I avoided anything having to do with Warhol. His looming reputation eclipsed my interest in learning more than what I already knew. I knew he was an artist—one of the greats. I knew he was a socialite. I knew he was white, gay, and American, born in Pittsburgh to Carpatho-Rusyn immigrants. Like many first-generation Americans of his time, he worked in a factory—though his, a silver-painted warehouse in Midtown Manhattan, became something else entirely. A product of the postwar boom, steeped in the country’s obsession with mass production, celebrity, and consumerism, Warhol turned icons of American life into high art.

Then I encountered poet John Giorno’s memoir, Great Demon Kings, 2020. The first third of the book chronicles his richly layered situationship with Warhol. The relationship burned out quickly; Giorno starred in Sleep (1964), and later that year, Warhol gave the young poet the cold shoulder. “I was his first superstar and I was the first one he got rid of,” he wrote. Giorno’s recollections cast Warhol, not as an untouchable godhead, but as a flawed, impulsive human. I grew curious to really know him, although I sensed it would be difficult to parse out a definitive answer. Warhol’s calculated opacity, his refusal to dispel rumors or clarify his intentions, made him impossible to read. Instead, I turned to the constellation of people who orbited him, his collaborators, muses, and inner circle, like Brigid Berlin, Billy Name, and Malanga.

Watching Malanga’s movies in search of Warhol might leave you with more questions than answers. Yet, they offer something more—a glimpse at the life of an artist figuring it out, framed by an intimacy with Warhol rarely found in his own work and a sense of the Factory in its heyday. Jacoby’s films, too, offer a tender, unvarnished portrait of a time, a place, and the people who shaped it. And perhaps, in that, we find something even more valuable than a mythic artist: a reminder that history is never a singular story, but a collection of lives, love, and lost moments waiting to be recovered.

“Gerard Malanga: Secret Cinema” is on view at the Harris Theater, 803 Liberty Avenue, Pittsburgh, on December 14.

“Roger Jacoby: Pittsburgh Stories” is on view at Wood Street Galleries, 601 Wood Street, Pittsburgh, through January 5, 2025. The films will be screened on December 14 at Harris Theater.

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

.webp)

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.jpeg)

.avif)

_11%20x%2014%20inches%20(2).jpg)

.avif)

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.avif)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

-min_result.avif)

.avif)

3_result.avif)

_result.avif)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

_result.avif)

%2520(1)_result.avif)

_result.avif)

_result.avif)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

-min_result.avif)

.avif)

.jpg)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

.jpg)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)