-min_result.avif)

The month was January 1972; Nixon was in office, and the U.S. was pulling troops from Vietnam; the Equal Rights Amendment was moving through Congress; and Title IX, prohibiting sex-based discrimination in federally funded education programs, was on the horizon. In a matter of months, feminist Gloria Steinem would launch the inaugural issue of Ms. Magazine, cementing the rise of second-wave feminism. Meanwhile, in Los Angeles, in an abandoned mansion in what is now known as Koreatown—a space priced at two dollars, that had once been a convent—Judy Chicago, Miriam Schapiro, and a group of female student artists were organizing a form of exhibition previously unseen.

Among them was Faith Wilding, a young artist whose contributions would help define the legacy of feminist art. With intensity and quiet resolve, she performed Waiting, 1972, a poem that distills women’s experiences into a haunting monotony of service and sacrifice. Alongside her spoken work, she created Crocheted Environment, 1972, a web-like installation woven from yarn and rope, referred to as the “womb room.” Both continue to be two of Wilding’s most referenced works, embodying her vision of the cyclical, communal, and primordial aspects of womanhood, as well as humanity’s relation to nature.

These formative pieces were part of “Womanhouse,” an exhibition that transformed the mansion’s dilapidated rooms into living manifestations of women’s lives. Organized under the auspices of the Feminist Art Program, founded by Chicago in Fresno in 1971 with support from the California Institute of the Arts, the project empowered women to explore the personal and political in a public realm. This visceral space drew thousands of visitors during its month-long run, establishing a new benchmark for feminist art. “We didn’t really expect it,” Wilding tells me, calling from her home in rural Massachusetts. “People had never been to a show like this; they didn’t know what to think. There were a lot of young school children wandering around who just found it so magical.”

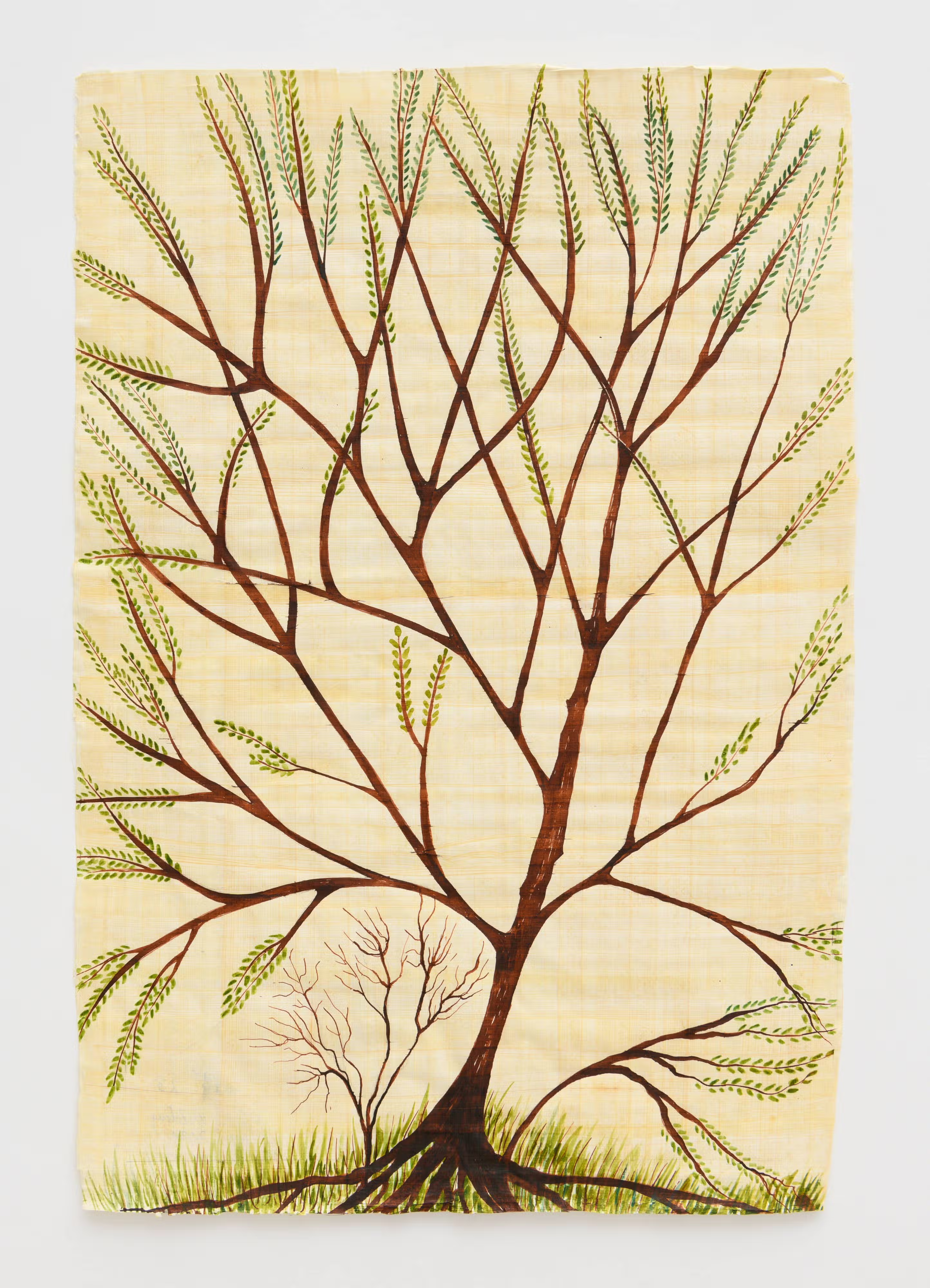

Over 50 years later, the ecofeminist pioneer is being celebrated with her first career-spanning survey. “Inside, Outside, Alive in the Shell” is on view at Anat Ebgi New York through March 1, 2025, marking her third solo show with the gallery. The exhibition includes painting, drawing, watercolor, papier-mâché sculptures, and papyrus scrolls, alongside notes, sketches, and other ephemera. Featuring over 20 works, the selection includes new 2024 paintings alongside foundational pieces like the 1993-94 Battle Dresses, dedicated to the women who were raped in the former Yugoslavia. Additionally, her “Scriptorium,” “Hildegard,” and “Rorschach Watercolors” series (initiated across the mid-80s to early ‘90s) illuminate a reverence for medieval aesthetics, as well as an exploration of subconscious forms. Together, these works trace Wilding’s artistic evolution, offering a fresh view of her continued engagement with biopolitics, life’s cycles, and spiritual exuberance.

Born into an Anabaptist commune in Primavera, Paraguay in 1943, Wilding’s upbringing was unconventional. Surrounded by the country’s lush, verdant forests, she spent her childhood immersed in nature. She would collect foliage and flowers, and wrap herself in banana leaves on walks with her father. “We were so surrounded by and dependent on it,” she explains of the natural world. Today, she is as curious as she was then, as in tune with her earthly surroundings as her child self—and as in love with poetry. She references the opening lines of Spring and Fall by the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins. “Do you know it?” she asks. The lines go: “Márgarét, áre you gríeving/ Over Goldengrove unleaving?/ Leáves like the things of man, you/ With your fresh thoughts care for, can you?” The speaker mourns leaves falling in a grove during fall, relating this period of transformation to the human experience of loss and the passing of time.

This cyclical process of shedding and renewal, of turning inward and looking forward, is central to Wilding’s work. It’s an awareness I feel most in tune with during winter, when, here in New York, the trees have finally shed their colorful shrouds. A time when many invoke Seasonal Affective Disorder, a form of depression tied to the lengthening nights, the summoning of this malaise feels, in many ways, like an attempt to articulate what Hopkins’ poem does so eloquently. Like the trees releasing their leaves in anticipation of spring, we often find ourselves reflecting on the year departing as we prepare for the one coming. Wilding’s art, much like Hopkins’ poem, invites us to explore the personal and collective shifts that occur over time.

As a young girl, the artist was enraptured with the writings of Virginia Woolf and the Brontë sisters. She was captivated, in particular, by Jane Eyre’s self-assuredness—a quality she has since harnessed in her own life. And she deeply resonated with German abbess Hildegard von Bingen’s mystical yet intellectual writings, which ranged from musings on nature’s “greenness” to the female orgasm. “I identify her as an early environmentalist,” she explains, mentioning her visit to Bingen’s nunnery as well as her posthumous dialogue with the figure in a radio segment she conceptualized in the ‘90s, now part of the Pacifica Radio Archives.

Considering where we are now in the climate crisis—having breached 1.5 degrees Celsius in Earth’s warming threshold—this retrospective couldn’t have come at a better time. The consequences of humanity’s disregard for nature’s limits are boiling over. Fires rage in Los Angeles, burning hotter and faster than ever before. These disasters, while part of a natural cycle in the dry West Coast winters, have been exacerbated by a perfect storm: eight months without rain, dwindling water reserves, and hurricane-level winds reaching 100 miles per hour. Across the globe, the evidence is impossible to ignore. Islands vanish beneath rising seas. Heatwaves scorch Europe. Droughts devastate crops in Africa. The global south struggles to cool itself as green spaces wane. It’s a nightmare from which not everyone has the privilege of waking. And yes, it is a privilege—the privilege of saying, “I don’t live there,” or “It didn’t happen to me.”

At what point does it become unthinkable to turn away from the reality that yes, it did happen—and it is happening—to everyone, everywhere? This is not a question I, nor Wilding, can answer, but it remains a question nonetheless. The artist, however, has always been a kind of soothsayer, drawing connections between the exploitation of nature and the systemic subjugation of women so deeply ingrained in the West. Beyond her ecofeminist work, Wilding is an activist and cyberfeminist trailblazer, having founded the art collective subROSA with fellow artist Hyla Willis in 1998. Stemming from American scholar Donna Haraway’s cyborg theory and the broader movement that emerged during that epoch, the collective’s influence inspired generations of artists and thinkers to reimagine technology’s role in shaping gendered dynamics. Technologist Mindy Seu’s Cyberfeminism Index, 2023, a now-printed archive cataloging seminal works in the movement, includes a 2014 project from subROSA, titled Down with Self-management! Re-booting Ourselves as Feminist Servers, which critiques enforced connectivity in digitized life.

We are alive and we are dying, this is the duality I imagine Wilding refers to in her 1977 text that anchors the exhibition. It’s one that many try to avoid thinking about. The fact can be daunting, but in embracing it as such, we acknowledge it as no different than the changing of leaves or the passing of seasons. Does Wilding believe in an afterlife? Not really. “I think we live in the memories of those that remember us and the work we leave behind,” she explains. She believes in her legacy and its impact on the collective imagination. “It is where people can find me.”

-min_result.avif)

As our conversation nears its end, I ask Wilding if there’s anything she’d tell her younger self preparing to perform Waiting. “It doesn’t belong to me anymore, it has been performed so many times and by so many people. It has lived its own life outside of me,” she replies. “If I met my younger self, I would say, ‘Yes, waiting is a hard thing to do. You know it, and I know it.’ It is something we can all relate to, and that’s what art is supposed to do, don’t you think?”

Faith Wilding: “Inside, Outside, Alive in the Shell” is on view until March 1, 2025 at Anat Ebgi New York at 372 Broadway, New York, NY 10013.

.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

.webp)

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.jpeg)

.avif)

_11%20x%2014%20inches%20(2).jpg)

.avif)

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.avif)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

-min_result.avif)

.avif)

3_result.avif)

_result.avif)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

_result.avif)

%2520(1)_result.avif)

_result.avif)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

-min_result.avif)

.avif)

.jpg)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

.jpg)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)