David Altmejd’s sculptures appear as if they are continuously morphing: a man into a rabbit, a woman into a killer whale, a swan into a saxophone. They are mercurial yet fixed in material and appear to be many things at once. Depending on the angle of La métamorphose du symbole, 2024, (“The metamorphosis of the symbol”) a two-headed swan’s form is either pregnant with an egg or the skull of a goat. But what I want to know is if works transform the artist, too? “Yes,” he answers, "but not right away, sometimes it's 10 years later.”

No matter how uncanny and otherworldly an Altmejd work presents, every sculpture begins with a shaven down cast of the artist’s head. Body parts might appear fragmented and glitchy, but they are his own, too. “At the core, at the heart, it came from me,” he says with a soft Québécois accent from his Echo Park studio nestled behind a garden in his backyard. Natural light pours in and lands on the shoulders of the few works in progress leftover from his show “Prélude pour un nouvel ordre mondial” (“Prelude to a new world order”), which opened this week at Xavier Hufkens, Rivoli in Brussels, Belgium.

Altmejd wears an unassuming dark T-shirt and pants, and a pair of small, emerald green gemstones glisten from his ears, hinting at the bejeweled flourishes he lends his works. His process is intuitive, grounded in the “intelligence of the gut,” as he refers to it. “As I work, the sculptures take shape on their own,” he explains. “There are invisible energies or spirits that are trying to manifest in the real world—I'm just helping give them form.”

One such work, Le don (“The gift”), 2024, depicts a ram with wide-set eyes and a human-like bust. He holds a scepter with a row of rainbow gemstones above a serpent in the middle, topped with a lilac rabbit’s head; in his other hand sits a small panther. Upon closer look, symbols appear on his horns, too. While his back is exposed, gray and almost decaying save for three buttons above his shoulder blades. In another, Le tunnel (“The tunnel”), 2024, a rabbit wears a black, fringe vest. On his chest is a drawing of a man holding a sword to the heavens. Where his eyes are: a crater. A woman rides or births a killer whale ecstatically in Nocturne no 1 (“Nocturnal no 1”), 2024—back arched, one hand digs into its flesh, while the other holds up a prism. Whenever a new work is born, Altmejd asks himself: "What part of me is it?”

Like his works, the artist is many things at once: curious, destructive, nurturing, sensitive, and rebellious. Originally from Montreal, he spent two decades in New York before making his way to LA in search of a quiet, pared down space where he could connect one-on-one with his peculiar and mystifying figures. “I just wanted to start over on my own, rediscover the connection between my hands and the material.”

For Altmejd, art, like a dream, is a platform for symbols from the latent to arise. It is transcendent, and it requires a surrender to the medium. To tap into another realm, he explains, he has to get out of his own head, enter a deeper space, and listen. “Even if I think that I'm in control of all the decisions I make, I don't know anything,” he emphasizes. “There's something else that's manifesting for the first time.” As he continues to develop his practice, he has become more in tune with this other side.

How does he quiet his thoughts to listen? He doesn’t. Instead, the artist comes up with tricks to make his mind work in a playful way. “I sort of sabotage my mind. Every time I know what it’s making, I push it in another direction. I go towards humor, and then if it's too fun I go towards something more dramatic… I end up with this thing that you cannot understand intellectually because it's going in so many places at once.” Mistakes excite the artist. For example, if he is sculpting and cuts the head in a certain way that makes it look disfigured, he might see the symbol of a whale and begin to coax it out.

While preparing for his current exhibition, he began seeing swans. The elegant birds began trying to surface in his work. Around the same time, the artist rediscovered a photograph of himself when he was 3 years old on the lake with his parents. Behind him, a large white bird. “It was way bigger than I was, and I remember feeling a sense of awe and being really intimidated,” he says. When the artist began to make musical instruments, the swan spontaneously emerged with a force that could not be ignored. In L’accord universel (“The universal agreement”), 2024, a cyborg-like man with splotchy skin and a brown mustache made of real human hair peeking out of a white helmet plays a swan like a guitar, while a cigarette rests in his ashtray. As Altmejd conjured his band of swan-musicians, he started thinking about the relationship between chaos and order and how he could join the two. “In the past, I always saw my role as an artist as trying to draw order from chaos,” he says, “but now I realize that's not what I'm doing. I have to let collaboration happen between the two.” He had an epiphany: Chaos is not just chaos. It's an energy force, a life force, a natural form. “Maybe I have to be more like a snake charmer,” he suggests.

When the artist touches his work, he can feel the energy, he tells me as he holds his hands against the side of the face of an unfinished sculpture, which will be presented in New York at White Cube in the spring. “It’s also another way of listening.” As he continues his practice, he has become more intune with the energy of his feminine sculptures: “They connect to a really deep, unconscious aspect of myself. It's an energy that has been trapped in the darkness for so long, and it really wants to manifest,” he says—an energy that he underscores is within everyone regardless of gender.

Altmejd cites Kali, the Hindu goddess who is often associated with a regenerative destruction. “It is both tender and protective, but it's not afraid to destroy to make room.” Many of his sculptures hold craters, gashes, and portals—they appear disfigured, transmogrified. At times, he takes his saw and begins cutting holes in his works, to release something inside, let light shine in. “People are like,” he gasps, “‘What are you doing?’ But I feel instinctively that it is what I need to do for something to grow… I need to make those radical holes.”

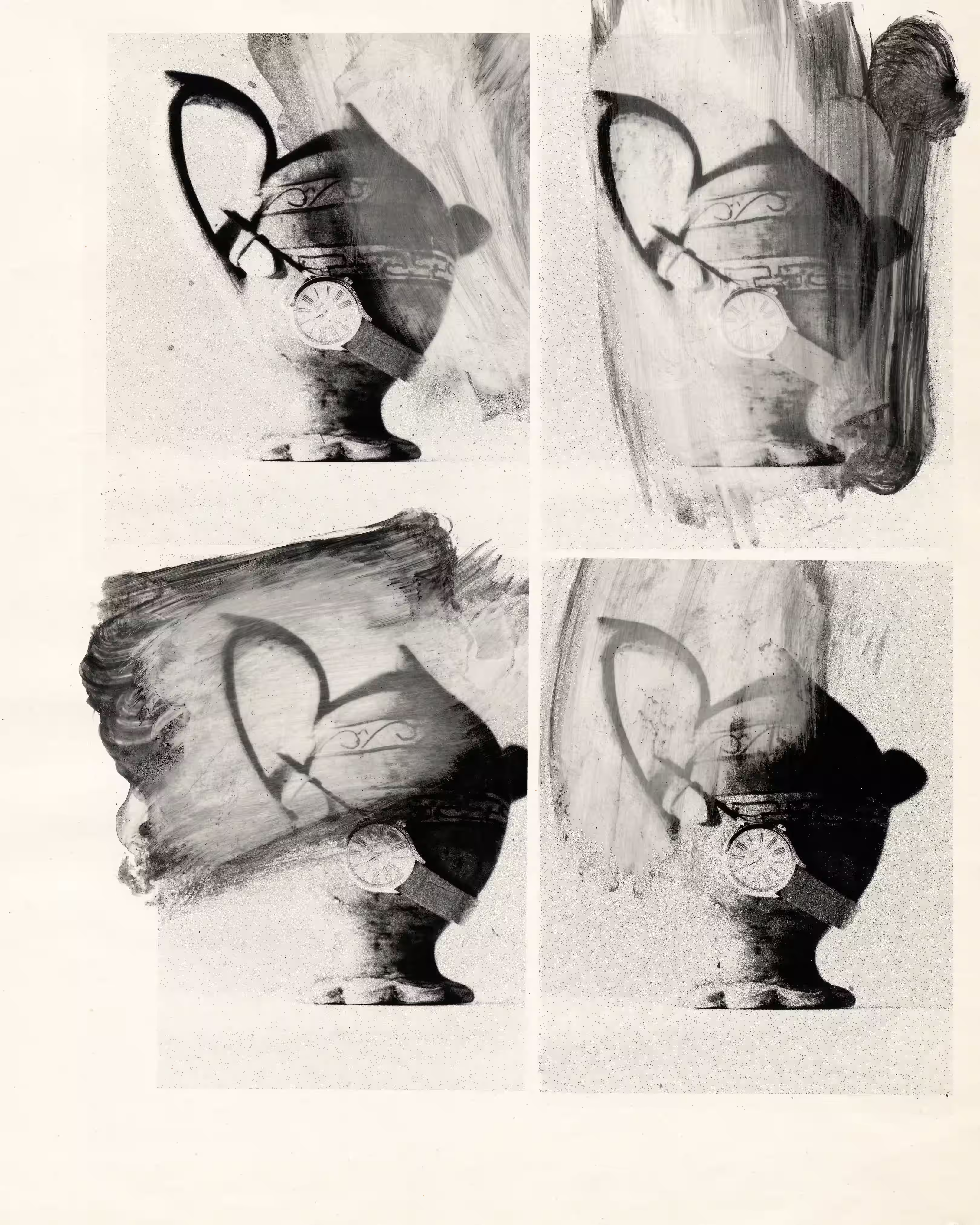

Following his instinct has also led the artist to begin separating his sketches from his sculpture. “I like to use the sculpture as a surface almost as if it is just a very intricate frame for a simple drawing,” he says with a laugh, noting that he uses the pencil as a final step to mark a work’s completion. Yet for the first time, his drawings are presented on works on paper as entities of their own at Xavier Hufkens. “Sculpture is the embodiment of a spirit that comes from another dimension—but at the same time, it always carries the weight of its physicality,” he says. With this physicality comes practical problems of material and structure. Drawing is devoid of that. “It doesn't have to carry any weight, so I see it as pure spirit.”

“Is there something that you've always wanted to make but haven't yet?” I ask. “No,” he answers, adding after a pause, “I never know what a work is going to look like; I'm just letting it take shape. It develops an intelligence and is able to make its own form. Everything that I do is decided from the inside of the object.”

David Altmejd: “Prélude pour un nouvel ordre mondia” (“Prelude to a new world order”) is on view through February 8, 2025 at Xavier Hufkens, Rivoli at Rue Saint-Georges 107, 1050 Ixelles, Belgium.

.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

.webp)

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.jpeg)

.avif)

_11%20x%2014%20inches%20(2).jpg)

.avif)

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.avif)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

-min_result.avif)

.avif)

3_result.avif)

_result.avif)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

-min_result.avif)

.avif)

.jpg)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

.jpg)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)