Driving into Prague from the airport, the first portrait you see is of Colonel Sanders appended to the cubic structure of a Soviet-style brutalist building, advertising a nearby KFC. Down the street, a mural renders Rihanna younger and with computer-cleaned skin, wearing a crown.

In 2000, when Heath Ledger was 21, and the dust of the Berlin wall was still being collected, he drove a similar path on his way to film A Knight’s Tale, Brian Helgeland’s anachronistic action-comedy that takes equal inspiration from medieval literature as it does ‘70s pop music. Bruce Weber followed suit to photograph the young actor exploring the city at the time. Markéta Tomková, the executive producer of Weber’s retrospective “My Education” at the Prague City Gallery, tells me that upon returning to the city for the opening of his show for the first time since his initial visit, the photographer noted how much times have changed for the better: people smile now, and they are willing to speak in English.

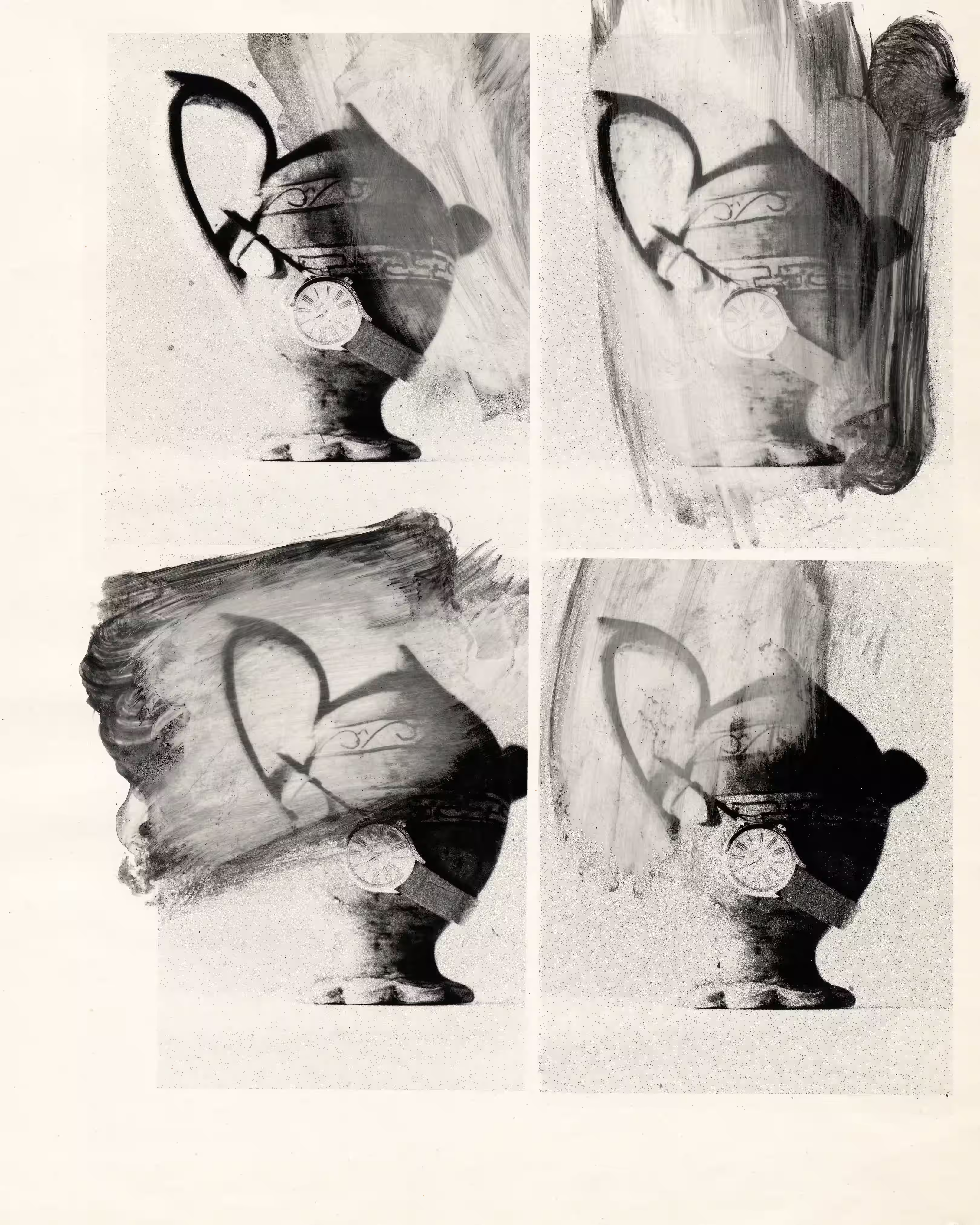

There are many looming absences, however. Ledger has passed. So have many of Weber’s earlier subjects. Others, like early supermodel Jeff Aquilon, have faded completely from public view; in fact, Aquilon had already done so by the time Weber first arrived in Prague. Yet the style of Weber’s photographs remains ever-present, in part because the images abide by the prevailing cultural gaze that he helped create. His majority black-and-white compositions anchor his subjects like statues, steeling them against any sense of day, much less any sense of time. The effect for viewers is that Weber’s subjects never die. Paradoxically, to never die also means to never be alive. His approach marks a distinctive way of remembering. Remembering, of course, invokes forgetting, too.

“My Education” marks Weber’s first career retrospective after more than half a century of defining the cultural appetite for taut, handsome men. The photographer first made a name for himself with his provocative images of young, nubile Adonides for imprints like GQ and brands like Ralph Lauren in the ‘80s. But Weber is a Renaissance man, a title that extends beyond his Petrarchan return to the kouroi-style posing he borrows from the Greeks. This survey builds beyond his better-known work in an expanded study of his lifelong inquiries, including those for which he is less recognized, spanning celebrity portraiture, fashion and street photography, reportage, and even landscapes.

-min_result.avif)

The exhibition is hosted across 17 rooms in the Stone Bell House, a 14th century landmark residence and the rumored birthplace of King Charles IV. The structure stands on the periphery of the Old Town Square, tucked in the shadow of the Gothic prismatic towers of the Church of Our Lady before Týn. Across two floors of the gallery, Weber’s photographs are hung or pasted in such a way that betrays a white-cube approach, one that has, for so long, attempted to render art inert by segregating it from its surroundings. The playfulness of Weber’s photography comes to life within its unique environs: Each room is cribbed by groin-vaulted ceilings and suffused with ecclesiastical detail. Triple niches along private oratories offer a place to sit; mullioned windows with re-plated baroque glass transfigure natural light.

Departing from his convention to hang his photographs with two-inch margins and recessive white frames, Weber experiments with arrangement across the exhibition: There are sculptural prints that stand atop floor-length mirrors, diaphanous banners hung from rafters, and images printed directly onto bespoke exhibition walls. The result of the latter is a feeling that the pictures have always been there, painted in tempera across the walls of a lived-in house, rather than a gallery. For the first two months of the exhibition, this sense of intimacy extended beyond the walls of the Stone Bell House to the lobby of the nearby Four Seasons hotel, where a replication of Weber’s personal library was installed and made available for visitors to peruse.

The sense of permanence garnered by these thoughtful constructions reflects the ethos of Weber’s photographic approach and the organization of the exhibition itself. Despite being introduced with both a biographical and cultural timeline, “My Education” skirts chronological telling in favor of an associative structure, whereby photographs across decades are grouped by their line of thematic inquiry, ranging from Walt Whitman, to musicians, to icons, to name a few examples. Sorted this way, it is easy to lose a sense of when and where photographs were taken. In many ways, the primarily black-and-white composition of these images places them outside of time. Even the documentary photos, taken in American prisons or late-century Vietnam, are consumed and anchored by the bodies of their subjects, muting any background to silence. Weber tends to emphasize the natural world instead of the built environment, the texture of naked skin rather than clothes. The effect is the disappearance of artifice that would otherwise date his work, making photographs like Boys at Butterfly Beach, 1982, apathetic to any concept of time.

The effect of Weber’s compositional consistency, ostensibly fully-formed from the outset of his tutelage under photographer Lisette Model in the late ‘60s, is particularly disarming when the same person reoccurs as a subject. Two images of Pedro Almodóvar taken across decades appear as if they were captured on the same day, giving the impression of the director as both father and son. Time is only implied when the same object is (rarely) pictured more than once; otherwise, Weber creates an indeterminacy of setting and a contextual ambiguity. Like the presentation of a homeless woman in Jeff Wall’s Approach, 2014, it is unclear (without the details of the wall labels written by Weber himself) whether images, like that of Kate Moss in Vietnam, are staged or spontaneous. The viewer’s attention is directed not to the interiority of his subjects but to his own psychology. Weber’s style is so distinctive that he nearly eclipses his subjects in the shadow of his implied presence.

The contradiction of immortality evoked by Weber holds something of a deconstruction: What steels his subjects against time is the very fact that they are often not treated as subjects, but as beautiful objects, projected by his psyche and made factual by his lens. Weber’s photographs veer more toward fantasy than documentary. They are sculptures of perfect bodies, beautiful and outside the malignant dribble of time.

Atemporality, however, does not imply ahistoricity. If history is typically conceived as a lineage of moments in time, then Weber discards such a paradigm, like Marguerite Duras and other authors of the French nouveau roman, in favor of a discrete physicality; a hierarchy that prioritizes the relation of bodies in space over time. Ultimately, then, his photographs in “My Education” do not present a kind of remembering, or forgetting. Instead, they are regenerative and reanimated, tethered to a stasis of perpetual re-presentation. In a world where change is a constant, the immutability of Weber’s style always feels recontextualized and new.

Bruce Weber: “My Education” is on view until January 19th at Prague City Gallery at Staroměstské nám. 605/13, 110 00 Old Town, Czechia.

.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

.webp)

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.jpeg)

.avif)

_11%20x%2014%20inches%20(2).jpg)

.avif)

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.avif)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%2001%20hr.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

-min_result.avif)

.avif)

3_result.avif)

_result.avif)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

-min_result.avif)

.avif)

.jpg)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

.jpg)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.jpg)

.avif)

.avif)