At a time when fairs are shrinking to match attention spans, EXPO CHICAGO's range feels almost radical. Founded in 2012 by Tony Karman, a veteran of Chicago’s art scene, it emerged after the collapse of Art Chicago due to waning influence. In a city often left out of the coastal art world tug-of-war, the fair positioned itself as a third center: less flashy than Miami, less insider than New York, and more expansive than Frieze LA, which hosted 97 galleries this year. Despite the pressure to keep up, Chicago moves at its own tempo, honing in on a belief in stories often left out of view. Across the fair, which just concluded its 12th edition, works by marginalized voices, meditations on migration, and visions of survival flicker into focus, serving as a reminder that art can still stretch toward connection, even as the world seems to splinter apart.

The East Wing entrance is typically the first entry point for most attendees. There stands Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Wrapped Package, 1961, a sculpture small enough to cradle. A soft bundle, wrapped in twine, it gestures toward both containment and offering. The late artists were life partners who truly saw each other, creating monumental installations together around the world. Part of the IN/SITU program—handpicked by Jessica Hong, chief curator at the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art—the work speaks to the section’s simple proposition: people in collaboration both in art and in life.

“Regardless of why people are drawn to EXPO, the connections we make here last,” Hong tells me in front of The Graduates (Princess and Bashira), 1989, a bright cast-plaster portrait of two South Bronx elementary school graduates, by John Ahearn and Rigoberto Torres. “Friends, curators, artists, people who really make up Chicago’s different communities,” she continues, as a friend of hers who just arrived interrupts us to say hello.

As I weave through the fair, I notice that people aren’t just browsing, they’re catching up, embracing, pulling each other toward booths like magnets. Even the artworks seem to pulse with human connection. Everywhere I look, eyes stare back. At Detroit-based Library Street Collective’s booth, one of 170 galleries present, I stand before Allana Clarke’s thick, black abstractions made from poured hair-bonding glue. The material dries into folds and creases, glossy in places, matte in others. “You can smell it if you get close enough,” Leah Rutt, the gallery’s registrar and director of operations, says, grinning. The tar-like glue has an unmistakably sweet, chemically floral scent.

At the center of the booth, a black box is topped with a looping screen that shows Clarke at work in her studio. A portal into her world where both her material—a product woven into Black beauty rituals—and her own body, moving like an embodied prayer, are inseparable from her art. Clarke’s process becomes a way of understanding Blackness. Not as something to be held or decoded, but shaped and lived, resistant to the outward gaze.

A few presentations away at Paris’ 193 Gallery, Sesse Elangwe’s portraits engage sight more directly. Born in Cameroon and now based in San Antonio, Texas, Elangwe paints figures where one eye is always slightly larger than the other. The eye is directional; it tells you where to look, and reminds you that you, too, are being witnessed. In Elangwe’s A gift from the Garden, 2025, a solitary woman stands among towering plantain trees. She wears a crisp, white dress with a bright red headwrap, and carries a glossy black Louis Vuitton tote. She peers beyond the canvas, past the viewer, watching something we can’t see. The tension lingers in what we don’t know. What is she looking at? What is her gift?

If Clarke and Elangwe turn witnessing into a symbol of intimacy and encounter, Rodolfo Abularach’s paintings, shown by David Nolan Gallery (New York) and Marc Selwyn Fine Art (Los Angeles), unmoor the eye altogether. Born in Guatemala’s capital in 1933 to Palestinian refugees, Abularach spent decades working between Central and North America, drawing from both Latin American surrealism and European expressionism. His obsessive renderings of the human eye verge on the holy, repeated until the gaze itself becomes cosmic with pupils stretched into thresholds and irises framed like eclipses.

It’s meaningful to see Abularach’s work here, in the city where he had his first American solo museum exhibition at Chicago’s Art Institute in 1961. “There’s a spirituality to Abularach’s practice that feels like something everyone needs these days,” his gallerist says, outlining “the aura of something deeply human but also beyond it, and in awe of what we on earth can only imagine.” Painted by an artist born oceans away from his homeland, Abularach’s eyes hover and multiply, suspended between memory and dream.

If eyes forge connections across time and space this year, Exposure—curated by Rosario Güiraldes, who leads the Visual Arts program at the Walker Art Center—offers the clearest articulation of why such visibility matters. Across the booths, works from historically marginalized voices open conversations around identity, migration, diaspora, and the urgency of being seen. Dedicated to 50 emerging galleries founded within the past decade, the section champions visions still shaping themselves in real time. “EXPO is a regional fair, but it’s a real portal into a broader, international art world for a lot of local collectors,” Güiraldes says. “You see artists finding their voices, but already joining conversations happening across places like São Paulo, Vilnius, Cape Town, and Mexico City.”

At Verve Gallery’s booth, director Ian Duarte introduces me to two Brazilian artists: Lita Cerqueira, widely considered the country’s first Black woman photographer, and Nádia Taquary, a contemporary sculptor whose practice draws deeply from Afro-Brazilian rituals and histories—both rooted in the Bahian city of Salvador.

Cerqueira’s black-and-white street photographs offer an unfiltered exchange between subject and artist. “The people she captures look right into the lens,” Duarte explains. That directness, that act of mutual recognition, carries political weight, too. “Of course, it’s different when a Black subject is photographed by a Black artist,” he adds. “The subjectivity changes.” Cerqueira isn’t an outsider looking in, she moves through these communities as one of their own. In her photographs, you sense that the people she captures meet her gaze with familiarity, trust, and shared understanding.

Nearby, Pittsburgh and New York galleries april april and Petra Bibeau present a two-person show pairing Mo Costello and Dionne Lee, two artists thinking through land, survival, and history in distinct but resonant ways. Costello’s silver gelatin prints document informal commons—front porches, thresholds, rural sites of gathering—with what april april’s Patrick Bova calls “a longing important to understanding survival, especially as a queer, disabled person in the rural South.”

In turn, Lee’s mixed-media collages deal with America post-Reconstruction, weaving fragments of survival guides, wilderness manuals, and archival landscapes into meditations on survival and memory. Across both artist’s work, absence operates as presence.

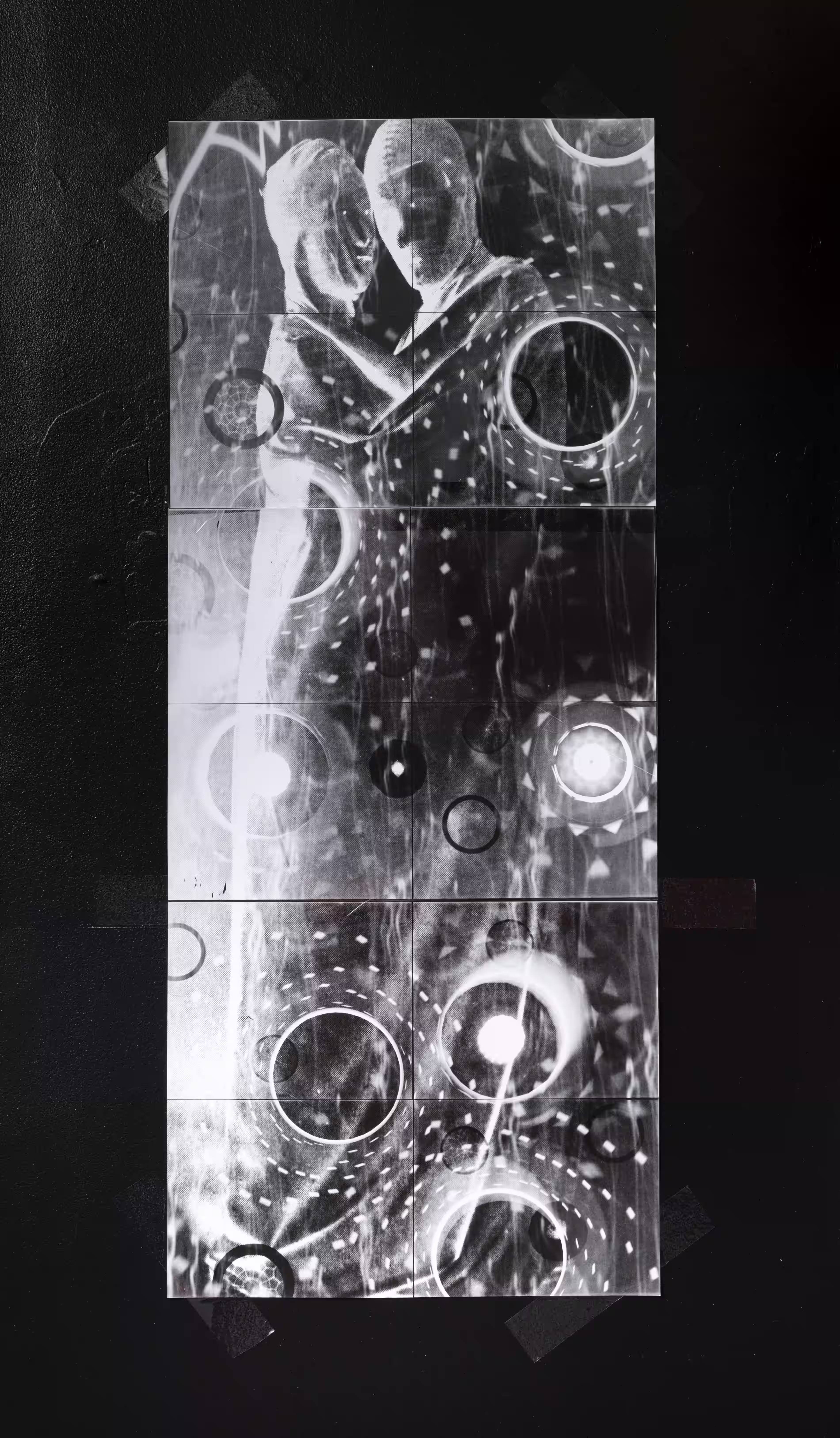

At Hudson Valley-based Bill Arning’s booth, Gabriel Martinez’s photo-based works reimagine queer archives through light, reflection, and memory. Martinez, who has long explored the textures of desire and survival, brings a playful yet mournful energy to the fair, revisiting the ecstatic visibility of queer nightlife and the spaces it shaped, and left behind.

Taken together, these artists, and the conversations they open, reflect the fair’s deeper undercurrent at a time when the country is becoming more fractured by the day. There is a desire for connection and the demand to be seen on one’s own terms. There is the notion that despite our differences, we shimmer the same under the sun. After all, that’s what an artist does; they show you different ways of seeing the world. The fair, at its best, isn’t only a marketplace, but a site where vision stretches far beyond what any pair of naked eyes can see.

.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

.webp)

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.jpeg)

.avif)

_11%20x%2014%20inches%20(2).jpg)

.avif)

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.avif)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

-min_result.avif)

.avif)

3_result.avif)

_result.avif)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

_result.avif)

%2520(1)_result.avif)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

-min_result.avif)

.avif)

.jpg)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

.jpg)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)